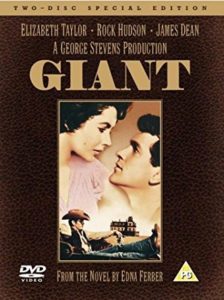

Giant: A Duel Edged “Modern” Western

Giant

Directed by George Stevens

Starring Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, and James Dean

1956

Giant is filmed in the beautiful but desolate wildlands near Marfa, Texas[1] by the excellent director George Stevens (1904 – 1976), who also directed the award-winning movie Shane (1953). Giant is based on a book of the same name by Jewish author, Edna Ferber (1885 – 1968). The movie is also the iconic actor James Dean’s final film. The live-fast actor perished at the age of 24 in 1955 before the film was released. Each scene in the movie is a work of art in-and-of itself. For example, the Victorian mansion that serves as the main hacienda for the Benedict family’s ranch, Reata, is an iconic contrast of high culture imposing itself upon a raw frontier.

Giant is a “modern” western. That is to say, that the movie is about “cowboys” riding and roping upon the range, but it occurs in a time contemporaneous to the film’s release. So unlike the many westerns that take place in the post-Civil War setting, this movie is like No Country for Old Men (2007) or Hell or High Water (2016). The film is also more than a “modern” western in that the story takes place over several decades – from sometime around the First World War until 1956.

The film follows the lives of Jordan “Bick” Benedict Jr. (Rock Hudson) and his wife Leslie Lynnton, (Elizabeth Taylor) as they raise their three children and manage their massive ranch. Included in this story is Jett Rink (James Dean). Leslie is a socialite from the upper-class Maryland horse-breeding set. Jordan is a Texan Rancher through and through. Jett is a hired hand who inherits an oil bearing patch of Reata when Jordan’s sister Luz Benedict (Mercedes McCambridge) dies. Luz had been angry about her brother’s marriage and had used sharp spurs on Leslie’s prize horse and been fatally thrown off.

Giant is an excellent film describing the lives of Texans who are seeking their fortune, furthering their legacy, and upholding their traditions in a high-risk/high-reward environment. However it is also a work of “civil rights” propaganda not unlike Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. These works of fiction bring to mind a saying of George Lincoln Rockwell, “…[O]ne is mad to permit himself voluntarily to be hypnotized by a novelist, transported out of his critical faculties and thereby to allow his mind to be powerfully conditioned by almost real ‘experiences’ which are nothing less than the invented devices of another human being.”[2] The movie’s propaganda message – its hypnotic power – works by showing reality, but warping that reality to manipulate the audience. It also omits describing large portions of reality.

Before deconstructing the “civil rights” propaganda, one needs to discuss what makes the movie powerful beyond its excellent cinematography. The first thing is that the marriage of Jordan and Leslie is well and seriously portrayed. In fact, their relationship exemplifies a good marriage. Leslie “landed” Jordan when he was visiting her father looking to buy horses. This courtship is not unlike that of Isaac and Rebecca in the Bible. Like the way Isaac could trace his roots to Ur of the Chaldees and went there to find a wife, Jordan Benedict’s Texas landholding class can trace its roots to Tidewater Virginia and Maryland. Marry someone of your social class and roots. Leslie had been in a courtship with Sir David Karfrey (Rod Taylor). The courtship was fairly conducted so that that when Leslie went off with Jordan, Leslie’s sister Lacy (Carolyn Craig) landed David. If you carry out fair courtships, one’s sister might be able to quickly marry well too.

Leslie Benedict doesn’t change her essence after getting married, but she does (with some key friction described below) adapt to her new circumstances. At the end of the film we know that she can manage the roundup, give wisdom and empathy to her children, and be a solid helpmeet for Jordan. Leslie also avoids the temptations of adultery although there is clearly some attraction to the dashing bad-boy Jett. When the marriage hits a rough patch and she returns to the exurban horse farms of Maryland, she decides to reconcile with her husband for her children and ultimately, for herself. By the end of the film, one really likes the Benedict family.

Giant warps reality in the scene where Leslie Lynnton Benedict approaches a group of men discussing politics. The men awkwardly dismiss her with the misogynistic statement, “don’t worry your pretty head…” Provoked, Leslie harangues the men with various feminist statements. The audience is meant to sympathize with the women, but the scene is warped so that one might not recognize that that the men aren’t talking about big issues of the day, they are manipulating local politics through less than honest deal making. We even see an older Hispanic named Gomez being given orders on how “his people” should vote. Giant cleverly shows, but masks through cheap-shot feminist emotionalism, the reality that wealthy, politically-connected Anglos like Lyndon Baines Johnson[3] and George W. Bush can use Hispanics to prop up and expand their wealth and power to the detriment of the rest of America.

Additionally, has there ever been a time in America since Abigail Adams or Dolley Madison that wives of powerful men were kept out of political talk? By the end of the film we see a second, more nuanced confrontation between Leslie and the men “talking politics” but the metapolitical framing is that of “white people” problems. There is a discussion of a tax write-off on oil production, but nothing about the racial powder-keg that Detroit was turning out to be in the 1950s. After all, we know now Detroit’s situation turned out to be more important to the rest of America than amusements for rich Texans.

Throughout the film there is an exploration of Mexican migrants in Texas, but it is only a partial look. The movie details the shanty towns and Third World conditions of the immigrants, but doesn’t ask why Mexican mestizos create Mexican conditions in Texas. The movie also ignores the very real conflict of interests between Texas Anglos and Mexicans. In this movie Mexicans are called names more appropriate to that of North American Indians (they are different so this is a fictional goof). There is also another warping of reality. Mexicans are seen as a harmless bunch, and are unfairly lumped in with blacks. Giant is one of the metapolitical cultural works that has created the inaccurate “blacks and Hispanics” against whites meme.

Because the film’s story is one of multiple generations and multiple decades, World War II comes in and catches all the young adults including the son, and son-in-law of the Benedicts. One young adult is one of the sons of a Mexican ranch hand named Angel Obregón II (Sal Mineo). Angel is killed during the war. His funeral scene is very well done and the flags, uniforms, and other outward trappings of patriotism appear like a conservative and traditional Texas A & M Event.

This is also a metapolitical emotional manipulation of the audience, and it deserves analysis. Military service can be used as an instrument of national unity, but it is a narrow reed and a dual-edged sword. Militaries must be able to recruit from as wide a pool of candidates as possible, but in doing so they run a very large risk. First, military service can empower and give military training to “diverse others” with negative effects. Mostefa Ben-Boulaïd, an Algerian Revolutionary in Algeria’s War for Independence (1954 – 1962) had served in the French Army during World War II and been awarded a Croix de Guerre – a fact which did not stop him from fighting France later. The Croix de Guerre was narrow reed indeed. Additionally, those who’ve done military service are entitled to above-average claims of citizenship and esteem, and with that in mind it can give an alien people claims on society that are also above average. For example, the Islamic activist Khizr Khan was given a national platform because his son had been killed in the Iraq War. While the Democrats lost the White House, they will not be locked out of power forever. When they return, Khan and his racial and religious attack on whites will be back again.

The movie’s climax is also an emotionally manipulative warping of reality. The Benedict family go to Sarge’s Diner. While eating, Jordan Benedict Jr. takes exception to Sarge (Mickey Simpson) throwing out a Mexican family. The Mexicans are elderly, small and harmless. Initially, Sarge tries to keep the matter discrete but Benedict intervenes. After several provocations from Benedict, Sarge finally directs some racial insults towards the mixed-raced Benedict baby and the fight is on. Sarge ends up knocking out Benedict and he drops a popular pro-segregationist sign that said, “We reserve the right to refuse service to anyone.”

The scene deserves some analysis. First, the scene is probably not based on any event that actually occurred. It is highly unlikely a diner in a sparsely populated place such as southwest Texas would refuse service to anyone, especially harmless, elderly Mexicans. On the western Great Plains of the United States, the population has been declining since the 1930s, so any paying customer would be highly prized. The scene is more a warped reflective of the Deep South’s supposed treatment of blacks, not the treatment of Hispanics by Texas. Additionally the 1950s, the Census Bureau had no Hispanic Category, so Mexicans were classified as white.

The fight scene instead should be seen as emotionally manipulative critique on Southern segregationist policies regarding blacks. The manipulation starts with the portrayal of the working class diner owner Sarge. After all, Sarge has cruelly insulted a baby and thrown out old people who are Mexicans. However, if one sees the scene as a critique of segregation of blacks one can see that since the “civil rights” revolution, we know the segregationists were right – at least right involving blacks in high numbers. Since desegregation, small numbers of blacks can be expected to behave reasonably well in nearly any public commercial setting, such as that of a restaurant. When their numbers get larger, the problems scale up. For example, Black Biker Week in in Myrtle Beach, SC is a fiscal disaster for local restaurants as the black patrons cause various problems and don’t pay their restaurant bills.[4] Scaled up from Black Biker Week are the black-ruled, nearly entirely black towns that have cropped up since the “civil rights” revolution are almost entirely barren of amenities such as grocery stores, theaters, restaurants, etc.

The scene with Sarge also shows the divisions that much of America have developed since the 1950s. In this case, a wealthy, upper class person attacks a working class white on behalf of a different people.

If Sarge Could be More Eloquent, He Might Say…

‘…Texans don’t let down your guard!” The problem in the American Southwest regarding Hispanics is less their behavior (like with blacks), but the fact that there is a smoldering border dispute, and the fact that American and Mexican political cultural forms are carried out on what Chilton Williamson called, “unrelated cultural and moral planes.”[5] For example, Mexico has had many Civil Wars that were far uglier than the American Civil War. Its political class is riddled with corruption. In Mexico, political assassination is the rule, not the exception. Mexicans and Hispanics are by no means a uniquely evil people — in fact, Americans should rejoice our southern neighbor is Mexico rather than Algeria, Turkey, or Morocco — but simmering border problems put a sharp, deadly edge on politics. The global catastrophe that was World War II started with a German-Polish border dispute that was not much different than the one between Texas and Mexico.

In Texas and the rest of the Southwest US, Anglos and Hispanics have had tensions leading to violent flair-ups for more than a century. Hostilities between the Texas Republic and Mexico existed from the end of the Texas War of Independence in 1836 until the end of the Mexican War in 1848. Following the Mexican War, the violence continued in the form of numerous border clashes. Some of these clashes escalated into pitched battles. During one of the Mexican civil wars (1910 – 1920), there was a plan by Mexicans to kill every Anglo in the Southwest and the Texas Rangers reacted quite sharply.[6] In 1919, El Paso and Juarez were the scene of a fracas that included a vigorous artillery barrage.[7] Skirmishes continue today.

After the fight with Sarge, Jordan Benedict must reconcile with his son’s interracial marriage. The interracial marriage allowed Jordan’s rival Jett, who’d grown rich by striking oil, to get some solid insults in at a black tie affair in front of Jordan’s social circle. Additionally, Jordan’s grandson from the marriage of his son to a Mexican ‘doesn’t look like him.’ Again this is a warping of reality: Mexicans from northern Mexico have considerably higher European blood, so in truth, his grandson would likely be mostly European with some Indian ancestry. I’ve known many mixed Anglo-Hispanic children that are completely phenotypically white. While these mixes aren’t optimal from a pro-white perspective we can see here that Giant is not talking about Hispanics, but blacks. Barrack Obama didn’t look like the white parents that raised him.

Giant is an excellent film, but as a metapolitical work, it helped cause Texans to lower their guard and in doing so, threatened the rest of America. All states are now border states with Mexicans able to snatch up low-end jobs and drive down wages with little trouble. Additionally, because of immigration policies enacted in part due to cultural efforts of movies such as Giant we are seeing the stirrings of trouble beyond the desert fringes of the Rio Grande Valley. In the Spring of 2017, the Texas House of Representatives was the scene of a violent confrontation between a white Anglo Texan, Matt Rinaldi and Hispanic Representatives Ramon Romero, César Blanco, and Poncho Nevárez.[8] The Hispanic Representatives and their protester backups were operating well within the violent norms of Latin-American political culture. For example, in Nicaragua, the various oppressive dictators used government-sanctioned mobs of “protesters” that “unofficially” physically threaten the opposition. These mobs are called Turbas Divinas, and now Austin has had a taste of them. We may all have a taste of them.

Notes

[1] http://www.npr.org/2011/07/15/138163048/on-location-50-years-of-movie-magic-in-marfa-texas

[2] Rockwell, George Lincoln, This Time The World, J. V. Kenneth Morgan, Virginia 1963 Page 34

[3] http://www.nytimes.com/1990/02/11/us/how-johnson-won-election-he-d-lost.html

[4] http://www.blackradionetwork.com/naacp_to_watch_for_discrimination_during__black_bike_week_

[5] http://www.vdare.com/articles/is-mexicos-constitution-of-blood-coming-here

[6] http://www.vdare.com/articles/the-plan-of-san-diego-then-and-now

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ciudad_Ju%C3%A1rez_(1919)

[8] http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/may/29/matt-rinaldi-assaulted-ramon-romero-over-texas-imm/