The Trial of Socrates: Introduction, Part 1

6,384 words

Part 1 of 2

The following text is a transcript by V. S. of the introductory lecture of an eight-lecture course called The Trial of Socrates. The lecture was delivered on September 1, 1998. I have previously published six of the lectures, but the Introduction and the final lecture, on Plato’s Phaedo, were thought to be lost.

Recently, I discovered the first lecture had simply been mislabeled. The final lecture is still lost, but I discovered a different lecture, given around the same time, that covers the same points about the Phaedo. When that lecture is transcribed, I will publish it here as well. I am considering recording new, high-quality audio versions of these lectures. As usual, I have edited this transcript to remove excessive wordiness and filled in the gap between the two sides of the tape.

Let me begin by just talking very briefly about Socrates’ life and teachings, and then we’ll start talking about why he’s so important, and why you should be here, and why you’re not wasting your time.

First of all, let me talk a bit about our sources on Socrates’ life. Socrates is an epochal thinker in a very literal sense, because there are epochs in the history of philosophy that are named in relationship to him. Before Socrates there is philosophy called pre-Socratic and after Socrates it’s called Socratic or post-Socratic. Just like there are years before Christ and anno domini. He is a watershed figure in the history of thought, just like Christ is in history in general. This makes him literally a pivotal figure in history. The hinges of history turn on the life and teachings of Socrates, at least the history of philosophy. And because philosophy has had such an influence on every other dimension of culture, really Socrates would have to be considered one of the human beings who has created the world that we live in, including shaping our minds in ways that we might not be aware of, unless we actually study what he taught and what he did.

So, this is not just a class about somebody called Socrates, because Socrates has put such a deep impression on human life and human history that it’s really a class about ourselves. Therefore, understanding him is a way of coming to understand the deep tangled roots of our own selves and our own minds and our own civilization.

Now, there are six sources of knowledge on Socrates. The first one, historically speaking, is Aristophanes’ play Clouds, which is a very nasty and very funny, bawdy, dirty-minded comedy that sends Socrates up.

The second set of sources are Xenophon’s Socratic writings. Xenophon was a younger companion of Socrates. He was a contemporary of Plato who was a general and a nobleman and had a rather extraordinary career. He became an exile from Athens near the end of the Peloponnesian War and spent a lot of time in retirement writing about Socrates. He also wrote the first novel called The Education of Cyrus, Cyropaedia. It’s supposedly a history of the founding of the Persian Empire, but it’s entirely fictional. So, it’s the first historical novel, too.

He is also the author of a wonderful military adventure, this time a true story, called Anabasis or The March Up, which recounts how, when he led an expedition to overthrow the Persian emperor and the army was defeated and caught, all the Greek mercenaries who had marched with a Persian rebel against the Persian emperor put him in charge of them to get them home, and it’s a story of how they marched home. It’s really a wonderful adventure story, and it’s true.

He wrote other works. Political works. A work on hunting. The kinds of things you’d expect from a Greek gentleman of the upper classes. But he was a very reflective man and grossly underappreciated today. And the reason why he’s underappreciated speaks directly to an issue we’re going to deal with when we talk about Socrates, which is the nature of irony.

Xenophon is one of the most ironic writers there is, and for the Greeks irony didn’t mean irony in the modern sense, when you say something, but what you mean to say is precisely the opposite of what you say. “We’re having a bit of warm weather,” that would be ironic or “a bit of cool weather” would be even more ironic given the context.

That’s not what irony means for the Greeks. Irony means a kind of aristocratic condescension. A refusal to show one’s self fully or speak one’s mind fully until one knows one is in the presence of one’s equals. And since when you’re writing a book there is no guarantee that the reader is your equal, you have to write in such a way that your meaning is obscure and that the reader has to be careful to read between the lines.

Xenophon is also an extremely funny writer, although his humor is so dry that many people described him as boring and stupid. So, he’s a very interesting and underappreciated source of knowledge for Socrates.

The main source of knowledge on Socrates are the dialogues of Plato, and we’re going to be reading excerpts or entire dialogues. Five of them total.

Another important source are testimonies from Aristotle, and I’ll read a few of these passages to you today.

A fifth source are assorted non-Platonic or non-Xenophonic Socratic dialogues. There are many of these works, and fragments of many of these works. Socrates had many followers and imitators, and some of his friends wrote down Socratic dialogues. Even Crito, who we will meet in the dialogue called the Crito, wrote Socratic dialogues. Even though he was really not very much of a philosophical man at all, he wrote dialogues recording conversations he’d had with Socrates. And there are fragments and entire Socratic dialogues, some of them anonymous, that have come down from antiquity. They’re all very interesting.

And then the sixth category, which is the “other.” There are all kinds of testimonies about Socrates’ life observed by historians like Diogenes Laertius or philosophers like Cicero, and we’re going to look at some of those testimonia today.

Because of all of these sources on Socrates, his life is fairly well-documented for a person who died in the 4th century before Christ.

He was born in Athens in 469 BC and he died at age 70 in 399 BC. His mother was a midwife, and his father was a sculptor. Sophroniscus was his father. Phaenarete was his mother. He had two wives: Xanthippe, who was a notoriously difficult woman to live with and with whom he had a son named Lamprocles. There are many stories about how difficult Xanthippe was. She was a real shrew. People asked him, “Socrates, why do you put up with this woman? She’s so difficult!” And he said, in effect, “Just like some people like spirited horses, I like a spirited wife. Besides, if I can get used to dealing with Xanthippe I can deal with anybody.”

She was with him almost until the very end, and then he had a second wife named Myrto, who had two children with him named Sophroniscus and Menexenus who were just babies when he died when he was age 70. It’s interesting that Xanthippe and the two young children are present at his death, which indicates that he had these children from a second woman while he was still married to his first wife, and there are some ancient sources that argue that this was exactly what happened. Namely, that the Athenians, because of the great loss of population during the Peloponnesian War passed a law allowing basically any citizen to take a second wife. Not officially, but sort of as a concubine to increase the population, so apparently Socrates did his civic duty even in his extreme old age by taking on a second wife and having two more children.

There are all kinds of odd stories about him. He was reputed to have helped Euripides write his plays, which is quite an extraordinary claim. He was reputed to have been a student of natural philosophers like Anaxagoras, Damon, and Archelaus. We’ll deal with that next week a bit. He was reputed to have never been interested in natural philosophy as well. He was rumored to have been a slave, which is probably entirely false. He was born the son of Athenian citizens, and he died an Athenian citizen. There’s no reason to think he was ever a slave.

He was supposed to have followed his father’s craft being a sculptor and was accredited with some great statues of the three graces at the Acropolis, and one poet named Timon wrote an epigram on this:

From these diverged the sculptor, a praetor about laws, the enchanter of Greece, inventor of subtle arguments, the sneerer who mocked at fine speeches, half-Attic in his irony.

He was supposedly a formidable public speaker and capable of persuading and dissuading people on any point. He was supposed to be the first teacher of rhetoric, which we know is historically false. According to one ancient historian, “he was the first philosopher who discoursed on the conduct of life and the first philosopher who was tried and put to death.”

He was supposedly, according to one person, a moneylender and an investor, although most sources say he lived in complete poverty and walked around barefoot and wearing dirty clothes full of holes. He prided himself on simple living, which is one of the sources of his conflicts with his wife. She wanted him to earn money, and he wanted to hang around talking philosophy. He really did value freedom rather than money or security, and so he chose to live in voluntary poverty in order to have as much free time as possible in order to think.

He did not travel at all except when he was sent on military expeditions by Athens during the Peloponnesian War. He was an exercise fanatic, apparently. He was very scrupulous about keeping himself in shape until he was very, very old. In fact, until he died. He was sometimes seen dancing alone, and he was asked why he would dance alone, and he said, “It’s good exercise.”

Frequently, because of the vehemence of the arguments he would get in with people he would meet in the gym or in the marketplace, people would set upon him, physically assault him, pummel him. He would also stand around the marketplace not buying things but talking philosophy, and he would like to look at the wares in the marketplace and exclaim, “How many things I can do without!”

He claimed, according to some sources, that virtue equals knowledge and vice equals ignorance, and we find that those are claims that are borne out in Plato. He was renowned for courage in battle and for moderation and self-control, and we find this attested to quite dramatically in Plato’s dialogue the Symposium. Alcibiades described how he slipped into Socrates’ bed at night and tried to seduce him, and Socrates remained completely unmoved by the whole experience, which is probably not an easy thing to do given that Socrates apparently had a wild crush on Alcibiades.

Now, the earliest dated event in Socrates’ life happened when he was 46 years old, and that’s when in 423 BC Aristophanes’ play the Clouds was premiered. It came in dead last in the competition of comedies in the great festival of Dionysos. Of course, all the other plays have long since disappeared in the sands of time, and this play has maintained itself as a classic ever since. Words of encouragement for any aspiring writers, I suppose. The Clouds is Socrates’ debut on the stage of history, and it’s a very unflattering portrait.

A couple of years later, 421 BC, is the date of one of Xenophon’s works called the Symposium, or the drinking party, and here Socrates is shown to be somewhat similar to the Socrates of the Clouds but somewhat different too. And we’ll talk about this as we go through the course.

He was sent off to fight a couple of battles during the Peloponnesian War, which lasted from 431 to 404 BC and ended with Athens’ defeat and the downfall of her empire. A few years after the war was over, Socrates was put on trial for a number of charges. We are going to look at this in great detail, but he was charged basically with disbelieving in the gods of the city, impiety, which, to the minds of the ancient Greeks, was equivalent to taking an interest in nature. For the ancient Greeks, natural philosophy or the investigation of nature by science or reason was equivalent to atheism, and we’ll see how that is the case, and that’s very much the portrait of Socrates you find in the Clouds.

Socrates was also accused of corrupting the youth by disbelieving in the gods and also by teaching them how to make the weaker argument the stronger, teaching them what has come to be known as the art of sophistry, the art of public speaking, the art of spin-doctoring. That might be our most exact contemporary analogue today.

Socrates was tried and condemned and executed in 399 BC. It was a fairly painless and humane death. They had him drink some hemlock, which caused him to expire. The Athenians were good to their own citizens even when they were executing them. They were remarkably humane for the standards of the time.

Socrates could have avoided the trial to begin with, it turns out, but chose not to. And he could have escaped from prison after he was condemned, but he chose not to and ended up dying. One of the things that we’re going to have to talk about in this class and puzzle over is why he did this.

Xenophon says in his Apology, or defense, of Socrates to the Jury, at the beginning, that people don’t understand that Socrates had decided it was time for him to die. That would explain his behavior. I think there is more to it than that, but it’s a start. It’s a very peculiar choice that he made at the end of his life, though, to suffer execution unjustly.

After he was executed, one of Socrates’ close associates, Aristippus, immediately brought charges against the people who put Socrates on trial. There were three of them: Lycon, Anytus, and Meletus. Meletus was executed, and the other two fled the city, because the Athenians suddenly had a fit of remorse over executing Socrates, and eventually they even erected a bronze statue of him at public expense in a public building. The most extraordinary thing came about as an unintended consequence of his death, namely the ideal of the “dying Socrates” became something that young Athenians aspired to. He seemed heroic and gained an extraordinary kind of mystique that clung to him throughout history. He’s a martyr for philosophy, and it really sealed his fame in the history books. That might have been part of his decision to remain and suffer execution.

Now, there are a number of points I want to make about pre-Socratic and post-Socratic philosophy and why this is significant. Why do we divide philosophy into pre-Socratic and post-Socratic periods? Because something very fundamental happened with Socrates.

First of all, philosophy before Socrates was pretty much amoral philosophy. There was no such thing as moral philosophy before Socrates. What you found among the pre-Socratic schools are two basic approaches to philosophy.

First, there was natural philosophy, which was simply what we would science today. We would call it value-free science today. The natural philosophers looked out at the world of nature and didn’t see any norms written in nature, any rights and wrongs. They just saw what we see today. Nature red in tooth and claw, the ugly struggle for survival, and that’s about it. They looked upon morality as merely a matter of social convention.

Another movement at the time known as the sophists, who were teachers of public speaking and how to get ahead in politics, also held basically the same framework. They thought that nature did not provide us any moral norms, but it did provide us certain desires, and the Sophists were there to equip people with the necessary tools to satisfy their desires to the best of their ability. And in ancient Greece the best way of satisfying one’s self in terms of one’s base desires was to go into politics.

Things haven’t changed that much I suppose, but for the ancients, politics was much more central than it is today. Anybody who was from a good family and wanted to make his way in the world would go into politics. It was simply not considered gentlemanly to go into business. That was a slavish activity. You were supposed to do business on the side to keep your estate functioning and so forth, but anyone who was seen to be too concerned with this kind of activity was looked down upon as a mere money-grubber.

The true activity of a free and noble individual was to engage in political activity, and so the sophists equipped people for politics. But the way they equipped them for politics was to teach them that beliefs about the gods and morality were merely conventional, that the teaching of nature was to satisfy one’s desires, and they should divest themselves of moral scruples in going about that activity.

So, neither strand of pre-Socratic philosophy had anything to do with morals. Morals were considered to be merely conventional and therefore somewhat contemptible, somewhat stupid. You’d have to be something of an unreflective buffoon to be concerned with morality.

Now, Socrates is entirely different. Socrates was primarily a moral philosopher, at least the Socrates we find in Plato and Xenophon.

I want to read a few passages. We’ll see these later, so you don’t need to worry about having the text in front of you. They’re all in the Apology of Socrates or the Crito.

In the Apology, (page 81, 30b in the margin), Socrates talks about his activity in the city.

I go around and do nothing but persuade you, both younger and older, not to care for bodies and money before nor as vehemently as how your soul will be the best possible. I say not from money does virtue come but from virtue comes money and all the other good things for human beings both privately and publicly.

So, the care of the soul, the cultivation of one’s moral character was the central concern for Socrates. And he said that you don’t get good character from getting money. You might have money coming to you if you cultivate good character, but there’s no guarantee about that either. But the primary concern for Socrates is the care of the soul.

Also in the Apology (page 92), after he’s been found guilty, Socrates says to the jury:

Perhaps then someone might say, “By being silent and keeping quiet, Socrates, won’t you be able to live in exile for us.” It is hardest of all to persuade some of you about this. For if I say that this is to disobey the god and because of this it is impossible to keep quiet, you will not be persuaded by me on the grounds that I am being ironic. And, on the other hand, if I say that this even happens to be a very great good for a human being, to make speeches every day about virtue and the other things about which you hear me conversing and examining both myself and others and that the unexamined life is not worth living for a human being, you will be persuaded by me still less when I say these things.

That’s a complicated passage but the gist of it is this: Socrates, before he was convicted, tried to justify the activity of going around Athens and conversing about virtue and encouraging people to leave off the things that impeded them from developing their souls and their characters. He argued that the reason that he went around doing this, which stirred people up and annoyed certain people, was that the god Apollo at Delphi had said that Socrates was wiser than anybody else in the world. And he said, “Well, pious man that I am, I realized that this couldn’t be true and I would have to go test what the god said.”

And so he went around finding people who had a reputation for wisdom, namely the sophists and the poets, who were also teachers of morals. If anybody taught morals in ancient Greece it was poets. Homer was the moral teacher for the ancient Greeks.

Socrates would go to people who recited Homer or people who taught public speaking, and he would ask them to display their wisdom, and they would come up wanting. They would fail, and so he’d go away thinking, “Well, you know, maybe I am wiser than these people. Why? Because they think they’re wise and they’re not, whereas I don’t think I am wise, and that’s true. I’m not wise.”

And so he says, in essence, “Maybe I have some kind of wisdom. Call it human wisdom, if you will, which is knowledge of one’s own ignorance and limitations.”

Now, in this passage he’s saying, “You didn’t believe that, you jurors. You didn’t believe that on account of the reputation I have for being ironic.” And we’ll explain what that means later.

So, paraphrasing again: “I’m going to tell you the true reason why I go around philosophizing now. It has nothing to do with the gods. It has to do with the fact that the examined life—the life of self-reflection and self-cultivation—is the only life worth living for a human being. Meaning that it’s intrinsically good to engage in philosophical reflection and self-criticism and self-examination.”

Philosophy is the care of the soul. The activity of philosophy is intrinsically good. It needs no other justification than the effect that it has on you. Socrates tried to fob the Athenians off with the claim that he was sent to philosophize by a god, but it didn’t work. But Socrates says it’s even harder to persuade them of the truth. The truth being that the unexamined life is not worth living for a human being, and the philosophical life is the only life worth living. It’s intrinsically good. That’s even harder to convince people of.

These are extraordinary claims, but it gives a sense of the centrality of moral philosophy and self-cultivation to Socrates’ project.

Now, I want to talk a bit about irony, because he says, “You didn’t believe me because I have a reputation for being ironic.” So, we need to know what it means to be ironic in the Greek sense.

For the ancient Greeks, irony has to be understood in the context of a rigidly hierarchical society which is ruled by a warrior nobility, a warrior aristocracy.

One of the hallmarks of aristocratic good manners and good breeding is that when you deal with people who are your inferiors, you don’t make them feel inferior. It’s crass and low-class to make people feel inferior. This attitude is very much present in Jane Austen’s novels. Think of Emma. Emma gets in big trouble from Mr. Knightley, which is the perfect name for a magnanimous man, because she makes people who are her inferiors feel inferior. “Badly done, Emma!” he says, “That’s the wrong thing to do.” This attitude was very much present, and traces of it still remain, in Southern genteel society.

A sign of good breeding is that you don’t make your inferiors feel their inferiority. So, how do you do that? Well, you have to be somewhat dishonest. You have to pretend to be less than you really are. It’s a kind of self-concealment and condescension designed to not ruffle the feelings of people who would otherwise feel put upon by their social superiors.

The crowning virtue of the gentleman, the upper-class person, the aristocrat, is called magnanimity: “greatness of soul.” But great-souled people, magnanimous people, when dealing with inferiors have to condescend to them. In order to prevent inequality of status from being painful, they have to downplay the distinction. So, they have to pretend to be less than they really are.

Now, if you look in Aristotle’s Ethics, if you look in Theophrastus’ book Characters, which are the primary sources we have from the time of Socrates on the nature of irony, this is exactly what irony is.

The modern sense of irony as saying something but meaning something different does not really come into existence until the century after Socrates’ death, and it’s not really formulated or defined clearly until the first century AD with the Roman orator Quintilian.

The primary sense of irony is this aristocratic, condescending, magnanimous refusal to display oneself fully. It’s a kind of sham. A kind of pretense. It’s a kind of dissimulation. Or it’s a kind of lying. A kind of dishonesty.

Socrates has a reputation for irony. What does that mean? It means Socrates feels superior to people. He knows he’s superior. He’s certain of it, but he doesn’t want to hurt their feelings, so he pretends to be less than he really is.

Unfortunately, however, people got a sense that he was doing this, and irony only works if people are unaware of it. No one likes to be condescended to, and if you know someone is being ironical with you, it pisses you off. And Socrates pissed a lot of people off by being ironical.

Irony is a way of lubricating social interactions between unequals so that differences of class or breeding or social status do not cause friction. But on the other hand, if you see through it, then it exacerbates those differences all the more.

Here’s Socrates, who goes around barefoot, looking like what would nowadays be described as a homeless person. And Socrates’ behavior would probably get him locked up as a schizophrenic. He walks around barefoot. He talks about philosophy. He says he has a little voice that talks to him and tells him what not to do. Once he stood up all night just thinking about something. He would go into little trances, basically, and lose track of reality. And when this bum condescended to the well-dressed, well-bred gentleman of Athens, and they saw through him, they felt deeply insulted. Because all of their good manners were being turned around against them, and they were being condescended to by somebody who appears to be by all conventional standards a total bum.

Socrates’ reputation for irony made his story that he philosophized out of piety to the gods completely unbelievable. The Athenians think Socrates is up to more than he admits, because he’s ironical. He’s talking down to us when he talks about the gods. That assumes, of course, that Socrates doesn’t really believe in the gods, which is one of the charges against him.

What’s the real reason Socrates philosophizes, then? Socrates reveals the truth when he says, in effect, “If you’re not persuaded by the gods, you’ll be even less persuaded by the truth, namely that there is nothing more important than the care of one’s own soul.” And that is hard for people to swallow. Most Athenians would not adopt Socrates’ lifestyle to save their own souls, much less care for them.

Now, Socrates is also reputed to claim ignorance. A lot of people, of course, take comfort in the fact that Socrates doesn’t claim that he knows, because, well, if Socrates can’t know, then who am I to be expected to know anything about virtue? And so one can sink back into one’s Barcalounger, click on the television, and that’s that. That’s really not the message one wants to take away from Socrates’ disavowal of wisdom.

So, I want to read the passages where Socrates talks about what he knows and doesn’t know. We will encounter this theme throughout the class. So we might as well get it in our sights beforehand, so that when we encounter it again it will be fresh in our minds.

In the Apology (page 68) Socrates says, “I, men of Athens, have gotten this name, this reputation for being a philosopher due nothing but a certain wisdom.” So, he does claim that he has a certain kind of wisdom. He doesn’t deny being wise. He claims that he has a certain wisdom. Just what sort of wisdom is this?

That which is perhaps human wisdom. For probably I really am wise in this, but those of whom I just spoke might perhaps be wise in some wisdom greater than human or else I cannot say what it is. For I at least do not have knowledge of it, but whoever asserts I do lies and speaks in order to slander me.

So, Socrates does avow wisdom, but he calls it human wisdom as opposed to a more than human kind of wisdom, which he does deny having.

To use terms completely out of context, he avows anthroposophy and denies theosophy. He has human wisdom or anthroposophy but not divine wisdom, theosophy. Those terms are being totally misused here. You shouldn’t associate it with Madame Blavatsky or Rudolf Steiner. But I’m just using the terms loosely.

On the next page, 68, he talks about how, after he heard the Oracle of Delphi saying that he was wise he said to himself, “I’m conscious that I’m not at all wise, either much or little.”

Now, I want to amend the translation there, because I think it’s better translated, “I am not wise in anything great or small.” That’s what he says. It’s more literal.

So, here he’s denying wisdom. But let me ask you, is great and small an exhaustive division of things? Is everything either great or small, so that if you have no wisdom great or small you have no wisdom at all? What’s being left out?

The middle-sized! The average! Now, what this refers to is the portrait of Socrates in the Clouds, because in the Clouds Socrates is shown having an interest in the feet of fleas and the anuses of gnats. Tiny little things. And he’s also shown to be interested in the cosmos as a whole and the Earth as a whole. The great things.

But when it comes to dealing with the middle-sized things, namely his friends and neighbors, his fellow human beings, the city, the human world, he’s a total boob.

In the Clouds, Socrates is portrayed as wise about great and small things and a fool in the middle-sized realm where human beings live. So, when he denies wisdom of things great and small what he is denying is the truth of the portrayal of himself in the Clouds as being interested in gnats and fleas and in the planets and the cosmos as a whole, and when he avows a human wisdom that’s equivalent to avowing wisdom about middle-sized things, namely us, the human world and human affairs.

Another sense of the “middle” is very important for Socrates. Socrates claims to know something. Not only does he claim wisdom about human things, he claims knowledge. He doesn’t disavow all forms of knowledge. He does claim to know certain things. And there’s one particular thing that he claims to know that I think is most astonishing.

In Plato’s Symposium, Socrates says “the only thing I say I understand is the art of love.” So, he does say he knows the art of love. Now, the Greek is just “the erotic things,” ta erotika. He knows the erotic things.

In the Theages, Socrates also says he knows the erotic things: “Rather I always say surely that I happen to know, so to speak, nothing except a certain small subject of knowledge that pertains to erotic things.” Or “erotic love.” Eros. “As regards this subject of knowledge, to be sure, I rank myself as wondrously clever beyond anyone, whether human beings of the past or of the present.”

Now, let me just state this. Socrates is not bragging about his sexual prowess when he talks about the erotic things, because if you read the Symposium, eros or love, is spoken of as a being that exists in the middle. The Greek term is metaxy, the middle realm, the middle space. And what’s it the middle between? Between mortals and the gods. Love or eros is treated as an intermediate being between the human and the divine. Not between the microscopic and the macroscopic, but between the human realm and the divine realm.

When Socrates claims not to have wisdom of things great and small but doesn’t deny knowing about the middle, that’s also equivalent to, I think, this claim that he knows eros, because eros is a god for him. Not a full-fledged god. A daimon is the Greek term. For the Greeks, a daimon refers to a quasi-divine being like an angel. It’s not mortal, but it’s not a full-fledged god either, and it hangs around between the realm of the gods and the mortals and carries messages and causes trouble. When Socrates claims that he has wisdom of the middle and knowledge of eros, that’s equivalent to the same thing.

What is knowledge of eros, though, for Socrates? Well, when you boil it down it means knowledge of the human soul. Because for Socrates eros is a kind of pulsating, plastic, vibrating force, the energy of the soul. It’s libido in Freud’s sense. The reservoir of psychic energy that sets the whole soul in motion. It doesn’t just refer to sexual libido. It refers to any kind of psychic energy and can take on any form, from attachment to another human being or one’s pets and one’s familiar surroundings to love of the fine or the beautiful, of the just, of ideals. Eros is a power that human beings have in the soul to form passionate attachments to things. Not just sexual things but also to ideals and so forth. To all of humanity or to things like justice or the good.

Plato believes and Socrates believes that the soul can be healthy or sick, and a healthy soul has a certain well-organized quality to it. It’s erotically well-balanced, whereas a sick soul is unbalanced, erotically speaking.

The hallmark of a healthy soul for Socrates is that it exists in this middle realm. It’s not caught up entirely in mere human affairs, in minutiae and trivia and the newspapers, because it also looks upward to things that are universal and ideal, and it tries to illuminate the messy flux of human affairs by something that’s not merely human, that’s ideal or universal in significance. So, there’s a kind of tension between the ideal and the merely real that exists in the healthy soul.

An unhealthy soul either collapses into trivial affairs and gets caught up in the merely human, all too human. Or another form of unhealth or illness to the soul is to become entirely indifferent to human things and solely identify oneself with what’s abstract or ideal. This is the kind of error of the ideologue. There are certain sorts of mysticism, asceticism, bodily self-denial, hatred of matter, what you call the gnostic impulse in philosophy that’s associated with the ancient Pythagorean school, for instance, who looked upon the body as a prison and the material world as evil as such.

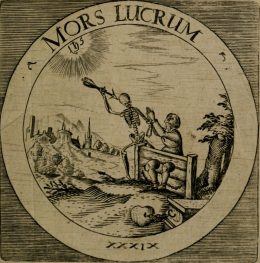

There’s a little emblem from the 17th century Rosicrucian named Daniel Cramer. The title is Mors Lucrum, which is Latin for “death is a profit,” “death is a gain,” and there’s an image of a man in stocks and in chains praying to death for release, and death is poised with its little arrow to deliver him. This is the gnostic attitude that the body is simply a prison and that death is our only route to freedom.

Socrates doesn’t have that attitude, because it’s too much a denial of man’s middle space. We can’t entirely leave the bodily world behind, and we shouldn’t be too concerned with that. Rather the ideal of psychic health is to maintain oneself in a constant tension between the ideal and the merely real, and an erotically healthy soul tries to maintain itself in that tension without collapsing into one pole or the other, without collapsing into one extreme or the other.

Part of what it means for Socrates to say he has human wisdom or wisdom about the middle things is to say he that has knowledge of how the soul can be healthy or sick, because he sees the soul as the primary thing, the middle realm that we have to be concerned with. The care of the soul, the cultivation of character, the health of our characters is his primary concern.

Now, Socrates is also reputed to have what’s known as his daimonion. Eros is supposed to be a daimon. It’s a quasi-divine being that’s between the gods and humans, and Socrates claims that he has a daimonion, which just means a “little daimon,” and we’ll find in the Theages and also in the Apology and the Crito that Socrates refers to his daimonion. It’s translated sometimes as the “divine sign.” And the “divine sign,” the daimonion, comes to Socrates and says, “Socrates, don’t do it!” Socrates is about to make a decision, and the daimonion says, “Wait, Socrates, don’t do it.” That’s all it says to him. It just stops him from making a bad decision.

It’s very interesting that, according to the texts of Xenophon and Plato, all the decisions the daimonion intervenes in concern human affairs. Socrates is about to get involved with something—with politics or with a certain student—and then the daimonion says, “No, don’t do it Socrates.”

Socrates uses the daimonion to personify his knowledge of erotic things, his knowledge of the dynamics of human character and how it can be made good and how it can go bad. The daimonion always warns Socrates away from dealing with bad characters. So, Socrates’ daimonion is his knowledge of human things, of the middle realm of the soul.

Robert Whitaker Remembered

Friedrich Nietzsche, born October 15, 1844

Game On: Revenge of the Matriarchs

The Color of Capitalism

Principalities & Powers, Part Five: The Bucha...

The Auction Block

Nietzsche, Physiology, & Transvaluation

Jordan Peterson’s Rejection of Identity Poli...