The Story of Benjamin Strong: How Fatal Conceit Wrecks Economies

by Peter Schiff, Schiff Gold:

In an article we published last week, Peter Schmidt highlighted what he called the “fatal conceit” of modern Keynesian economics. These economists, central bankers and politicians think they can plan, direct and guide the economy through their great wisdom and application of their economic models. But as economist Friedrich Hayek explained, the central planners’ arrogance ignores the knowledge problem. No individuals or groups of individuals, no matter how many PhDs they have among them, possesses the knowledge necessary to foresee all of the consequences of a given policy.

In an article we published last week, Peter Schmidt highlighted what he called the “fatal conceit” of modern Keynesian economics. These economists, central bankers and politicians think they can plan, direct and guide the economy through their great wisdom and application of their economic models. But as economist Friedrich Hayek explained, the central planners’ arrogance ignores the knowledge problem. No individuals or groups of individuals, no matter how many PhDs they have among them, possesses the knowledge necessary to foresee all of the consequences of a given policy.

As financial guru Jim Grant once put it, “We are the prisoners of the very dubious set of pseudo-scientific pretentions that are part of the people who manage our monetary affairs.”

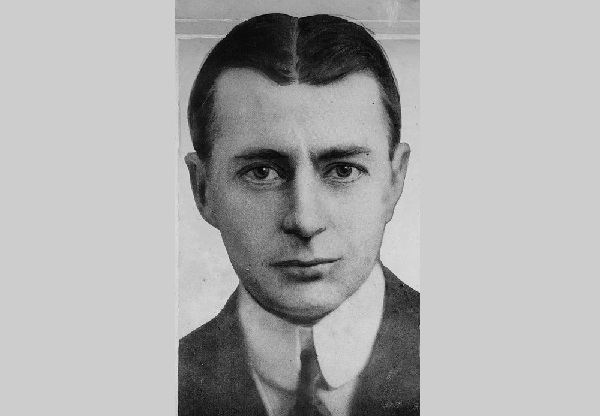

In a follow up to his last article, Schmidt puts an exclamation point on this idea of fatal conceit, recounting the maneuverings of Benjamin Strong, New York Federal Reserve governor from 1914-1928.

![]()

The following was written by Peter Schmidt. Any views expressed are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of Peter Schiff or SchiffGold.

The movie “Goodfellas” captures many of the details of the December 1978 robbery of the Lufthansa cargo terminal at New York’s Kennedy airport. One of the subtle details not fully developed was the robbery was only made possible because of the enormous gambling debts owed by a Lufthansa employee, Louis Werner, to a mob-connected bookmaker, Martin Krugman. In the movie, there is a scene where the robbery’s mastermind, James – “Jimmy the Gent” – Burke discusses killing Krugman. Burke asks his protégé, Henry Hill, “You think (Krugman) tells his wife everything?” Hill, who doesn’t want to see Krugman killed, responds, “You know him. He’s a nut job. He talks to everybody. You see his commercials, acting like a jerk. Nobody listens to what he says. Nobody cares what he says he talks so much.”

To a certain extent, Hill’s response concerning the bookmaker Martin Krugman is useful in evaluating the practical significance of the economist Paul Krugman. Because Paul Krugman talks so much, most people have long since stopped listening to him. Indeed, in my most recent post, “Paul Krugman, the Federal Reserve and the Fatal Conceit of Economics,” Paul Krugman was only discussed as someone who is thoroughly infected with the fatal conceit of economics. (Recall that the “fatal conceit” of modern economics is the belief the economy can be completely controlled by merely manipulating interest rates.) To be sure, as a Princeton professor and through his New York Times editorials Krugman is in a unique position to make his thoroughly bogus ideas heard. However, he is not in a policy-making position and, by that standard anyway, his ability to inflict damage on the US is somewhat limited.

Regrettably, any sort of limit on the Fed to cause damage via the “fatal conceit” of modern economics does not exist. In the brief discussion below, the most spectacular example of the fatal conceit of modern economics animating the Fed to cause enormous economic damage will be reviewed. This example involves a man named Benjamin Strong. This episode took place during the 1920s but should not be dismissed as irrelevant today. Strong was the governor of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from 1914 until his death in 1928. In this position, Strong essentially – and singlehandedly – ran the Federal Reserve.

While many people believe war is some sort of great boon to any economy, the experience of England after WWI provides definitive evidence to the contrary. Well before American had entered the war on the side of the Allies, England had borrowed enormous amounts of money from American banks to purchase weapons from American companies. [i] With the war over, these debts needed to be repaid. However, because all the borrowed money had been used to build weapons and not to increase England’s productive capacity, there was essentially no way for England to repay its enormous war-debts – owed in dollars – to the United States.

Investors realized that England had greatly increased its money supply without increasing its productive capacity. As a result of this, the British pound plummeted in value. In February 1920, the pound dropped to a low of $3.18. The pre-war parity had been $4.8668 per pound. [ii] Strong and his counterpart at the Bank of England – a thoroughly incompetent, central-planner named Montagu Norman – then conspired to return the pound to its pre-war parity with the dollar. They resolved not to do this by working together to make the pound stronger; instead, they worked – in nearly total secrecy- to make the dollar weaker. They reasoned that if the dollar was made weaker, the pound would become stronger as a result.

Loading...