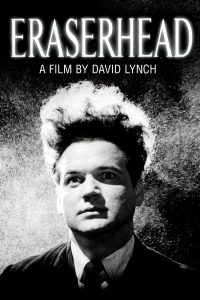

Eraserhead: A Gnostic Anti-Sex Film

David Lynch’s first movie Eraserhead (1977) combines surrealism, low-budget horror, and black comedy. It rapidly became a staple of the midnight movie circuit and provided endless fodder for coffee-house intellectuals and academic film theorists.

Eraserhead is quite simply a gnostic anti-sex film. The film is premised on a gnostic dualism, which holds that the material world—including sex and childbearing—is fundamentally evil, a prison in which the spirit suffers. The solution to suffering is to free ourselves from the trammels of matter, including sexual desire.

Eraserhead was filmed intermittently, on a shoestring budget, over a period of five years (1972–1977). Although the meaning of the film is self-contained, it is illuminated by some details in Lynch’s biography.

For instance, beginning in 1973, Lynch began his lifetime engagement with Hinduism and Transcendental Meditation. He has reportedly described Eraserhead as his most “spiritual” work.

From 1966 to 1970, while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in Philadelphia, Lynch lived in a hellish urban environment like the one seen in Eraserhead.

In 1968, Lynch’s first child, Jennifer, was born while he was still in art school. The pregnancy was unplanned, and Jennifer was born with severely clubbed feat, which required extensive corrective surgeries.

In 1974, Lynch’s marriage broke up, due in part to his infidelity.

Eraserhead opens with a planet in space. Then the sideways face of the main character, Henry Spencer (Jack Nance), floats up from the bottom of the screen in front of the planet (which can be seen through him) and drifts out of the frame. A throbbing sound grows louder and louder as we zoom in on the rough surface of the planet. Then we follow a trench until the screen is utterly dark. Next we see a metal-roofed shack on the surface with a huge hole in its roof. We enter the hole. Inside, we see a man with horribly disfigured skin seated in front of levers. In the background is a cracked and broken window.

We then cut to Henry’s face. His mouth opens, and what looks like a hypertrophied sperm cell comes out. Then the Man in the Planet pulls a lever, and the sperm whooshes out of the frame. Another lever seems to start a huge machine. The camera moves to a pool of water. Then a third lever sends the sperm splashing into the pool. Then we see bubbles and darkness. After that, we move toward a white circle of light, which seems to be glimpsed through a hole in gauze, fringed with hairs or threads. At which point the prologue ends.

The meaning of the prologue becomes clear when we learn a bit later that Henry has fathered a baby with his estranged girlfriend Mary—or at least a hideously deformed something that they think is a baby. Henry’s head and mouth of course are stand-ins for his penis, from which sperm cells actually emerge. The pool of water into which the sperm falls is Mary’s womb. And the movement from darkness to light is the birth of the baby.

The fact that this process is under the control of the so-called Man in the Planet gives it all a sinister cast. Sex and reproduction are material (the planet is a great hunk of matter, pulled into a spherical shape by the force of gravity), mechanical (produced by a huge machine), and directed by the malevolent will of the Man in the Planet, whose deformities emphasize his materiality and who is a kind of Gnostic Demiurge figure, imprisoning the spirit in matter.

After the prologue, we see Henry’s face, looking back over his shoulder anxiously, as if he is being stalked. He is dressed in a suit with a pocket protector. His hair is teased up in a huge bouffant. He carries a brown paper bag through an industrial hellhole back to his tiny apartment. Before he enters, a beautiful brunette emerges from the apartment across the hall. The brunette is a temptress figure, who in this scene calls to mind Franz von Stuck’s Sin. The brunette tells Henry that someone named Mary called to invite him to dinner at her parents’ house. After an awkward silence, he thanks the woman and goes inside.

Henry’s apartment is a strange place. It is furnished with a table, a record player, a dresser, a tabernacle-like cupboard, a bed, a night stand, and a couple of lamps. What seem to be grass clippings are piled on top of the dresser and on the floor under the radiator. The night stand is decorated with a mound of dirt from which protrudes a denuded branch. A tiny picture of a nuclear mushroom cloud hangs above it. In the top drawer of his dresser, Henry finds a picture of Mary torn in two. Obviously their relationship has been strained.

The next scene, dinner at Mary’s house, is the dark comic high point of the film. The scene begins with Mary’s worried face peering out of the window of her house, which is set in an industrial hellscape with a front yard filled with dead flowers. Like Henry’s apartment, the interior is drab and depressing. There are grass clippings here too.

Henry’s meeting with Mary’s parents is filled with excruciatingly awkward silences, during which we hear constant mechanical rumbling and hissing, as well as the loud sucking sounds of a litter of nursing puppies. Both Mary and her mother have spastic episodes. Mary’s father Bill has a loud voice, a benumbed arm, and a demented grin frozen on his face. The less said about the chicken, the better.

Then an electrical socket begins sparking and a lamp glows brightly then burns out, which in Lynch’s cinematic language signifies the presence of the supernatural. The mother then confronts Henry with a very awkward question: “Did you and Mary have sexual intercourse?” The question is followed by some intensely awkward nuzzling from the mother.

The reason she asks is that Mary has had some sort of . . . baby. Mary questions whether it is a baby at all, but the mother insists that it is a baby, a bit premature perhaps, but a baby. She also insists that Henry and Mary get married and raise the child. Henry takes the news by getting a nosebleed. All told, dinner could have gone better.

The next scene takes place a short time later. Henry and Mary are apparently married and living together with the “baby” in Henry’s little room. The “baby” is a grotesque creature. It looks more like a fetal puppy than a human being. Basically, it is a hypertrophied sperm cell with eyes and a mouth. Its body is hidden in bandages. Apparently it has no arms or legs. Mary is becoming increasingly frustrated feeding the “baby,” which writhes, fusses, and spits out its food.

Henry goes to the lobby to check the mail. He finds a tiny package in his mailbox. Furtively, he ducks out to the street to open it, finding a tiny worm inside. He returns, a hopeful smile forming on his face, and lies down on his bed to soak up this scene of domestic bliss, staring into the hissing radiator. When Henry looks into the radiator, a light shines from inside it and an empty stage appears. Henry is pulled back from his reverie by the baby crying. When Mary asks if there is any mail, Henry lies and says no.

Cut to a dark and stormy night with the baby crying. Henry gets out of bed and places the worm in the tabernacle-like cupboard, which emits a hum that grows louder when Henry opens the doors. Mary lies awake, tense, frustrated, and sleepless, listening to the baby cry. Finally, she loses her cool, leaps out of bed, and screams “Shut up.” Then she dresses and declares she is going back to her parents’ for a good night’s sleep.

Before she departs, Mary kneels at the foot of the bed, peering between the bars of the metal bedframe like a woman in prison, yanking on the bed, causing it to rock and squeak. Is she pantomiming her imprisonment to the baby and the material realm? Is she having another spastic episode? No, she’s just trying to dislodge her suitcase from under the bed. After Mary departs we see the temptress coming down the hall looking wet, tired, and sultry.

On his own, Henry wonders if the baby is sick and decides to take its temperature. The temperature is normal, but suddenly the baby is covered with vomit and hives. Its breathing is labored. So Henry rigs up a vaporizer. At one point he glances at the tabernacle then moves to leave, perhaps to check his mail, but the baby starts crying whenever he tries to leave.

Cut to Henry in bed, at the beginning of another sleepless night. The radiator hisses. We hear metallic grinding. Two metal panels part, and we see the stage in the radiator, footlights coming on one after another. Then the Woman in the Radiator appears. She is blonde and wears a white dress. Her face is disfigured with huge round cheeks whose wrinkled texture makes them look like a scrotum. She begins dancing to the organ music that Henry played earlier on his phonograph. Her manner is girlish and demure.

Then sperm cells begin to fall onto the stage. The Woman in the Radiator regards them with childish excitement, but when the organ music stops, he gleefully squishes one beneath her shoe. The music resumes then stops, whereupon another sperm is crushed. The wind then howls, and the Lady retreats back into the shadows.

Is the Woman in the Radiator’s girlish and demure behavior just an act put on by a dominatrix who excites fetishists by crushing things under foot? Perhaps. But if so, this is only a minor element of her role. Instead, I see her as an embodiment of asexuality and innocence, a Vestal Virgin whose purity is guarded by deformity, whose role is to crush and reject the deformed products of Henry’s sexuality. If the Man in the Planet represents bondage to matter and sexuality—which is embodied by the hideous and demanding “baby”—the Woman in the Radiator represents freedom from matter and sexuality, as well as the responsibility of parenthood. If the Man in the Planet is the Demiurge, the Woman in the Radiator is Sophia, the divine spiritual/intellectual principle that allows us to be saved from the bondage of the material realm.

Metaphysically, the realm in the radiator is the opposite of the planet in the prologue. The light is the opposite of the darkness of the planet. The stage suggests a realm of imagination, spirit, and freedom, rather than the planet’s realm of matter, gravity, and mechanical compulsion. The music in the radiator contrasts sharply with the mechanical rattle and hum of the planet. If the radiator is heaven, the planet is hell. These contrasts point to a neat gnostic dualism of matter and spirit, bondage and freedom.

When the Woman in the Radiator fades into the shadows, we see Henry tossing and turning in his bed. He wakes up to find that Mary is back, locked in a deep slumber, her face glistening with sweat. Her teeth are clicking together. She rubs one eye, making a gross squishing sound. She is hogging the bed, and Henry tries to force her onto the other side. Then, in horror, he reaches down and finds a sperm cell in the bed. He throws it against the wall, causing it to explode. Then he finds another and another and another. At this point, it is clear that the sperm are coming out of Mary, that she is writhing in the pangs of labor. This is how the “baby” was brought into the world. Mary’s bed hogging, writhing, sweating, teeth chattering, and eye rubbing—as well as the fact that she is unconscious the whole time—emphasize her corporeality and make it thoroughly revolting.

The sperm cells have been splattered against the wall next to the tabernacle cupboard, whose doors now open to reveal the worm, which springs to life and begins squealing. It retreats into the darkness of the cupboard and then appears to be on the surface of the planet, squealing, writhing, doing somersaults, plunging into one hole and then emerging from another. On its last emergence, its end opens up in a vast, all-devouring maw, not unlike one of the sandworms of Arrakis. Mechanical noises grow louder as we plunge inside and then see Henry, apparently from the point of view of an observer in the planet, perhaps the Man in the Planet himself. The worm is sensate flesh, deprived of all higher faculties, capable only of cavorting and suffering on the material plane (the planet) where it is imprisoned without hope of release. But Henry is more than just a worm. He has higher faculties (Sophia) that might just save him. But he’s due for another test, which the Man in the Planet has dispatched. Cue a knock on the door.

To be continued . . .

William Butler Yeats: A Poet for the West

Unity Valkyrie Mitford:August 8, 1914–May 28, 1948...

Heidegger at Neverland Ranch

North American New Right/Counter-Currents Site Lau...

The Vast Majority of Non-Muslims are Peaceful

Masters of the Universe

The French Anti-Revolution

The Solipsist Society