The Puzzle of Electrum Coins

by JP Koning, BullionStar:

For several years Brits have been hearing rumours that their 1p and 2p coins were on the cusp of being discontinued. Not so. Last month the UK Treasury announced its commitment to both coins. The 1 and 2p coins will continue to be produced for ‘years to come.’

Few bits of monetary technology have enjoyed as long an existence as the coin. The earliest coins were produced around 640 BC, some 2600 years ago, by the Lydians, who had built an empire in the western half of what is now Turkey.

To most of us, the usefulness of coins is self-evident. Sure, small coins like the 1p are a bit of a nuisance. They tend to accumulate in our pockets or piggy banks, never used. But compared to barter, or exchanging bits of unrefined metal, coins are a much better alternative.

One would assume that’s why the Lydians created coins in the first place: convenience. But the true story is much more puzzling than that. To this day we don’t entirely know why the Lydians began to turn precious metals into circular discs.

The Traditional origin story for Coins

The classic story for the adoption of coinage involves the efficiency gains that society enjoys when trade can be conducted by tale rather than by weight. Tale is a sum or a tally. All modern payments are done by tale. A payor counts up the right amount of coins (or notes), then passes the stack to the payee who – if they wish – can glance at the inscription on each coin’s face to ensure that it is legitimate. Circulation by tale is a convenient way of doing business.

But we take it for granted. Before coins appeared on the scene 2000 years ago, numismatists believe that people typically transacted with silver ingots and bars, otherwise known as hacksilber. These pieces could be cut up into smaller amounts in order to cover a range of different transaction sizes.

Because the bits of hacksilber were irregularly shaped, or non-fungible, they couldn’t by counted. Rather, they had to be weighed first, and only then could the transaction proceed. Weighing different bits of silver is a laborious process. A scale must be produced along with a set of weights that both the buyer and seller can trust.

Counting is much easier than weighing. If the stamp on the coin is reliable, buyers and sellers can trust to issuer to have already pre-weighed and standardized the metal for them. And so coinage would have dramatically reduced lineups and waiting time in busy markets all across the ancient world. What a fantastic invention.

Perfectly Standardized

At first glance, Lydian coins have all the hallmarks of this classical origin story.

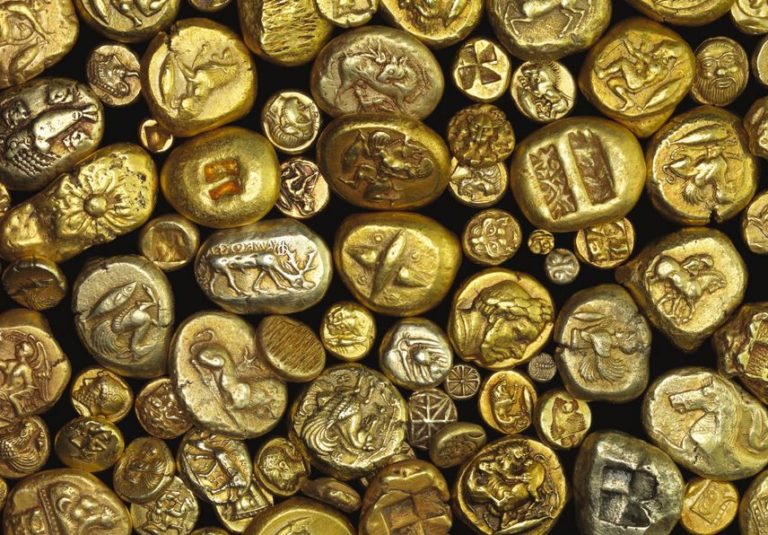

To begin with, they are quite beautiful. Each coin was typically stamped on the obverse side with a design in the form of an animal, human, or myth. On the reverse, or back-side of the coin, a square or rectangular design appears. Did these designs constitute some sort of official guarantee of the coin’s weight and fineness? Or did they symbolize something else?

The coins generally lacked any sort of writing on them. Numismatists are thus unsure who actually issued the coins. Was it the city, the king, a merchant or some other rich individual?

One fact that all numismatists agree on is that the Lydians were assiduous to a fault about ensuring standardized weights for their coins. The biggest denomination, the stater, weighed 14.1 – 14.3 grams. Half staters contained half as much metal, followed by third staters (or trites), 1/6, 1/12, 1/24, 1/48, and 1/96th staters, the last of which contain just 0.15 grams of metal.

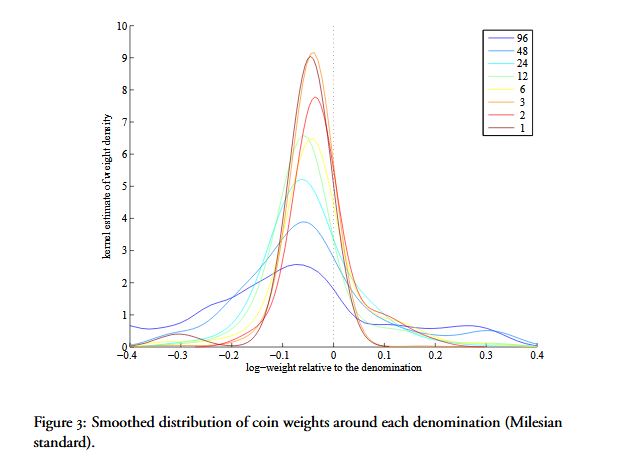

Francois Velde, an economist at the Federal Reserve who dabbles in numismatics, has catalogued thousands of Lydian coins owned by private collectors and museums around the world. Using this data, one can see the remarkable precision of Lydian coinage (see chart above). The weight of the largest coins – staters and trites – tend to be tightly clumped near the standard weight.

Interestingly, the smallest denominations – the 1/96th staters – are much more loosely distributed around the standard weight (see the dark blue line). Velde (2012) attributes some of the lower accuracy of smaller denominations to the fact that they would have circulated more, and thus deteriorated faster.

The inconvenience of Electrum

By carefully calibrating the weights of each denomination and stamping them with a seal, surely Lydia qualifies as the first society to make the technological leap to circulation by tale. But it’s here that the story begins to fall apart.

One of the curious facts of early Lydian coins is that they were made from a material called electrum. Electrum is a naturally occurring alloy of silver and gold, often found in streams and rivers. The problem with natural electrum is that the mix between gold and silver is variable. The silver content can be anywhere from 10% to 30%, according to numismatist Robert Wallace (1987).

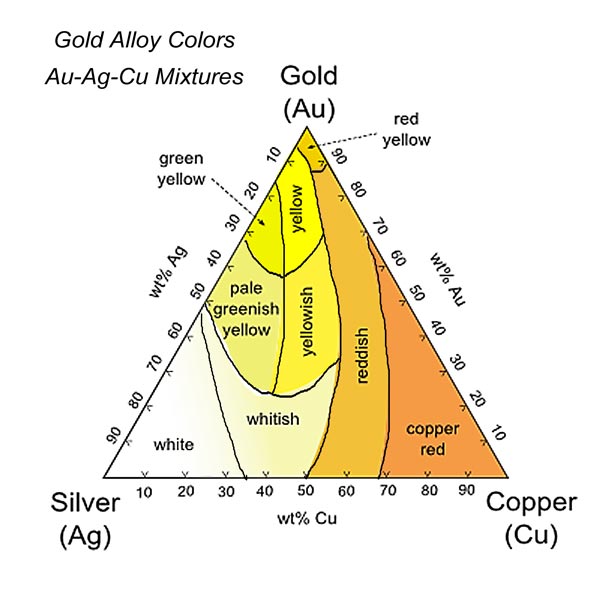

Given this variability, Lydians must have had difficulties valuing electrum. A given electrum coin wasn’t fungible, or interchangeable, with its cousins. A coin with more gold in it would have a slightly different colour than one with less gold, as the chart below implies. And since gold was probably worth around 10 times more than silver in ancient times, electrum coins with more gold in them would have had a much higher intrinsic value than those with less. But how much more? According to Wallace, this lack of certainty would have caused “endless doubts and disputes over particular coins.”

What a contradiction Lydian coins are! The Lydians had evidently gone to extreme lengths to perfectly calibrate coin weights, and thus potentially exchange coins by tale, only to undo all the benefits of standardization by making coins with an arbitrary gold-silver mixture. Now buyers and sellers would have to settle on some laborious means of determining a given coin’s mixture, say like using a touchstone, before they could consummate a trade.

The Lydians could have avoided this problem at the outset by issuing coins using silver rather than electrum. Silver, after all, was already traded in ingot form. With silver coins, at least there would be no confusion about intrinsic value. But the Lydians chose not to go this route.

Which leads us to what may be the most popular theory for electrum coins, what I will call the “token” theory.

Electrum Coins as Tokens

It is Robert Wallace who can be credited with creating what is probably the most widely-accepted theory for electrum coins. Wallace (1987) began by imagining himself in the shoes of an owner of an electrum hoard around 640 BC. This individual had the following problem. His stash of metal was not uniform, and so fellow Lydians didn’t really trust its quality. How could our electrum owner get his suspicious counterparts to accept his metal for its full value?

Loading...