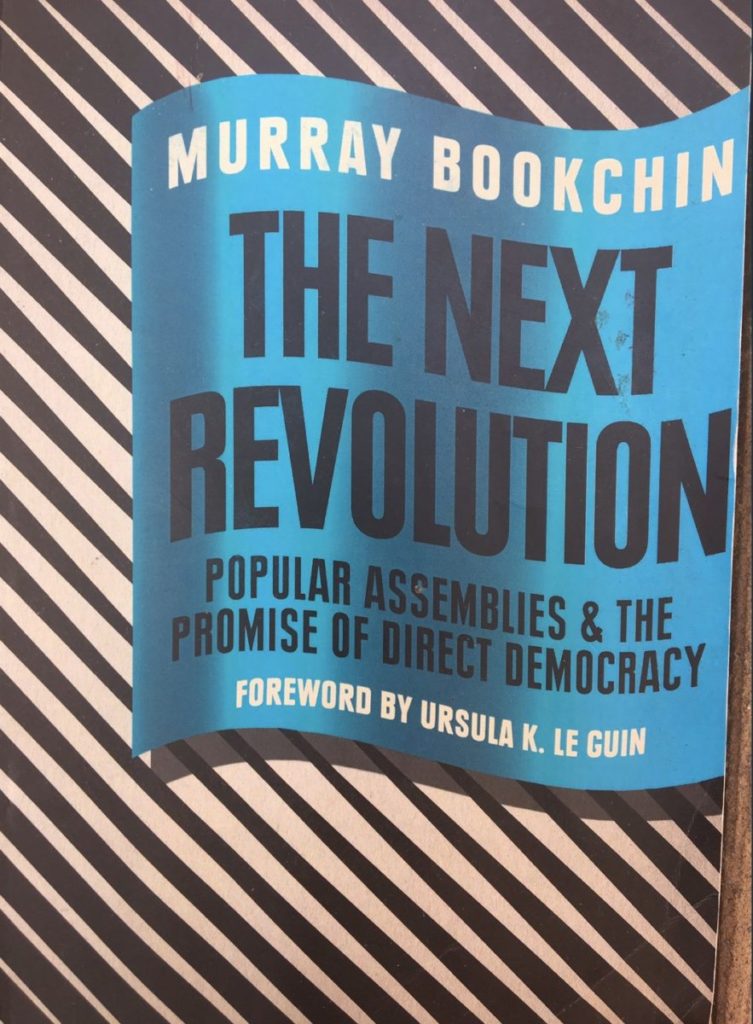

The Next Revolution by Murray Bookchin

by Michael Krieger, Liberty Blitzkrieg:

We cannot content ourselves with simplistically dividing civilization into a workday world of everyday life that is properly social, as I call it, in which we reproduce the conditions of our individual existence at work, in the home, and among our friends, and, of course, the state, which reduces us at best to docile observers of the activities of professionals who administer our civic and national affairs. Between these two worlds is still another world, the realm of the political, where our ancestors in the past, at various times and places historically, exercised varying, sometimes complete control over the commune and the confederation to which it belonged.

We cannot content ourselves with simplistically dividing civilization into a workday world of everyday life that is properly social, as I call it, in which we reproduce the conditions of our individual existence at work, in the home, and among our friends, and, of course, the state, which reduces us at best to docile observers of the activities of professionals who administer our civic and national affairs. Between these two worlds is still another world, the realm of the political, where our ancestors in the past, at various times and places historically, exercised varying, sometimes complete control over the commune and the confederation to which it belonged.

– Murray Bookchin, A Politics for the Twenty-First Century

Today, the concept of citizenship has already undergone serious erosion through the reduction of citizens to “constituents” of statist jurisdictions, or to “taxpayers” who sustain statist institutions.

– Murray Bookchin, Cities

In the spirit of my recent interest in direct democracy and the future of human governance, I finally got around to reading something that’s been on my radar for a while. It’s a collection of nine essays by the late political philosopher Murray Bookchin published together in a book titled:The Next Revolution – Popular Assemblies and the Promise of Direct Democracy. It did not disappoint.

While there are numerous key points on which Bookchin and I would have disagreed spiritedly, that’s not the purpose of this piece. Aside from being a wealth of information and knowledge (he closely studied nearly every major revolution in the Euro-American world), his greatest service here is a framework through which to understand human governance and how and why it’s all gone so terribly wrong. Many of his themes cover ideas and realizations I’ve come to on my own, but the clarity with which he describes certain key concepts helped refine my thinking. The purpose of this post is to outline some of these ideas.

The most fundamental and significant distinction he emphasizes is the difference between what he calls “statecraft” and “politics.” Statecraft is something done by “the state,” as opposed to politics, which is something done by humans engaged in self-governance. It goes without saying that the modern world is filled with statecraft and very little politics, as properly defined. So much so that we erroneously use the term politics to describe statecraft, something Bookchin finds dangerous and disingenuous.

If statecraft is the practice of using the instruments of the state to exercise power, we need to define what “the state” is. Bookchin offers his own definition in various places.

In The Communalist Project he notes:

Historically, politics did not emerge from the state — an apparatus whose professional machinery is designed to dominate and facilitate the exploitation of the citizenry in the interests of a privileged class.

In The Need to Remake Society he writes:

To create a state is to institutionalize power in the form of a machine that exists apart from the people. It is to professionalize rule and policy-making, to create a distinct interest (be it of bureaucrats, deputies commissars, legislators, the military, the police, ad nauseam) that, however weak or however well intentioned it may be at first, eventually takes on a corruptive power of its own.

One would have to be utterly naive or simply blind to the lessons of history to ignore the fact that the state, “minimal” or not, absorbs and ultimately digests even its most well-meaning critics once they enter it.

The notion that human freedom can be achieved, much less perpetuated, through a state of any kind is monstrously oxymoronic – a contradiction in terms.

In Nationalism and the National Question, he notes:

Nation-states, let me emphasize, are states, not only nations. Establishing them means vesting power in a centralized, professional, bureaucratic apparatus that exercises a social monopoly of organized violence, notably in the form of its armies and police. Te state preempts the autonomy of localities and provinces by means of its all-powerful executive and, in republican states, its legislature, whose members are elected or appointed to represent a fixed number of “constituents.” In nation-states, what used to be a citizen, in a self-managed locality vanishes into an anonymous aggregation of individuals who pay a suitable amount of taxes and receive the state’s “services.” “Politics” in the nation-state devolves into a body of exchange relationships in which constituents generally try to get what they pay for in a “political” marketplace of goods and services.

Finally, in The Future of the Left, he writes:

What constitutes a state is not the existence of institutions but rather the existence of professional institutions, set apart from the people, that are designed to dominate them for the express purpose of securing their oppression in one form or another.

Bookchin considered the state to be an aberration, a tool of domination and a cancer on human society. Although statecraft is often sold to the public as democracy or self-government, in reality it is nothing of the sort. It’s the difference between what he would call “professionalized power” (the state) vs. “popular power” (politics).

As Bookchin notes in Libertarian Municipalism:

More importantly, it involves a redefinition of politics, a return to the word’s original Greek meaning as the management of the community, or polis.

The word politics now expresses direct popular control of society by citizens through achieving and sustaining a true democracy in municipal assemblies — this as distinguished from republican systems of representation that preempt the right of the citizen to formulate community and regional policies.

In Cities, he explains:

But democracy, conceived as a face-to-face realm of policymaking, entails a commitment to the Enlightenment belief that all “ordinary” human beings are potentially competent to collectively manage their political affairs — a crucial concept in the thinking, all its limitations aside, of the Athenian democratic tradition and, more radically, of those Parisian sections of 1793 that gave equal voice to women as well as all men.

Bookchin was a huge supporter of direct democracy, in other words, of the people making decisions for themselves within their own communities. He envisioned this being done in a face-to-face manner within public assemblies. Like myself, Bookchin believed this sort of thing would only work properly (and resist statist tendencies) if employed at the local level. He understood that centralization leads to statism and vice versa.

Read More @ LibertyBlitzkrieg.com

Loading...