And the US Dollar’s Status as Global Reserve Currency?

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

Renminbi gains, but in painfully slow micro-steps. Dollar & euro combined share slides.

Renminbi gains, but in painfully slow micro-steps. Dollar & euro combined share slides.

How long can the US dollar maintain its status as the global reserve currency and as global hegemon? That’s a question that comes up a lot, particularly among people who’d like to see it knocked off its perch. So here we go.

Total global foreign exchange reserves in all currencies ticked up to $11.4 trillion in the first quarter 2019, according to the IMF’s just released COFER data. USD-denominated exchange reserves rose to $6.74 trillion, with their share of global foreign exchange reserves ticking up to 61.8%.

These are USD-denominated financial assets (US Treasury securities, corporate bonds, etc.) that central banks other than the Fed are holding in their foreign exchange reserves. The Fed’s own holdings of USD-denominated assets, such as its Treasury securities and Mortgage-Backed Securities acquired as part of QE, are not included in “foreign exchange reserves.”

The US dollar’s role as a global reserve currency declines when central banks other than the Fed shed their dollar-denominated holdings and replace it with assets denominated in other currencies.

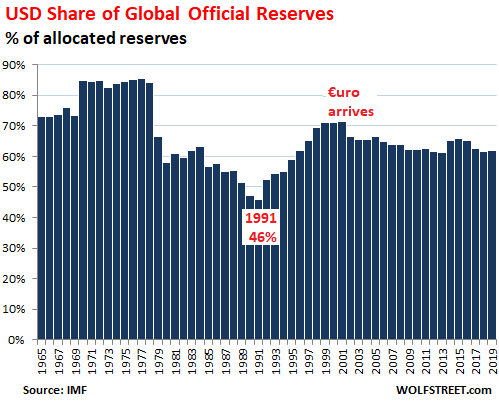

There have been two potentially big changes over the last two decades: The creation of the euro at the turn of the century; and in 2016, the Chinese renminbi.

The euro, the first big change, replaced the national currencies of EU member states, starting with five currencies – including the Deutsche mark which had been one of the major reserve currencies, but way below the dollar. As this change was taking place in phases, the dollar’s share dropped from 71.5% in 2001 to 66.5% in 2002.

There are now 19 member states in the Eurozone. The effort to eventually consolidate all European currencies in one big currency was powered by the hope of knocking the dollar off its hegemonic perch. At the time, the talk was about how the euro would eventually achieve “parity” with the dollar. But the euro debt crisis interfered, and the euro’s share of foreign exchange reserves has gotten stuck at around 20%, putting the kibosh on any “parity” hopes. In Q1, it’s share fell to 20.2%.

The Chinese renminbi, the second big change – well, “potentially” big change – was included in the IMF’s currency basket, the Special Drawing Rights (SDR), in October 2016. This elevated the renminbi to an official global reserve currency. Expectations that the renminbi would quickly knock the dollar off its perch have also been disappointed: It’s moving only at a snail’s pace.

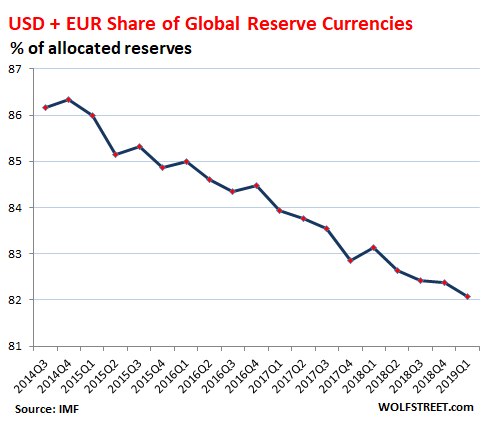

The dollar and the euro combined accounted for a share of 82.1% in Q1. This is down 4 percentage points from 2014 (86.2%):

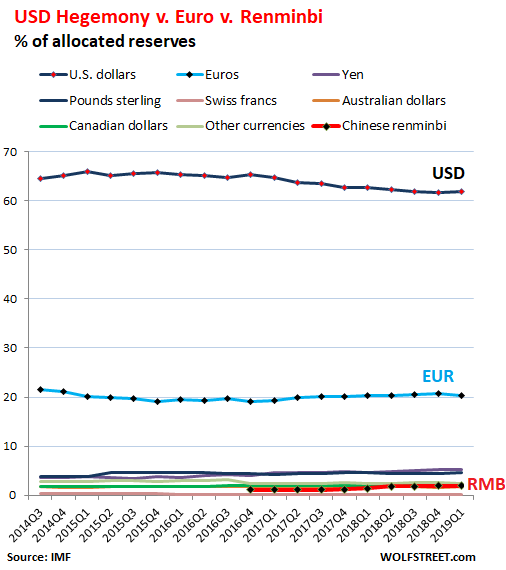

The chart below shows the overall scheme of things concerning the share of the top reserve currencies. The dollar dominates. The euro is second. Both are quantum leaps ahead of the remaining top reserve currencies, the dense spaghetti at the bottom of the chart. The renminbi (RMB) is the red line near the very bottom:

As small as the renminbi’s share still is, it is gaining on some other currencies. In Q1 2019, with a share of 1.95%, it is in fifth place (in Q4, 2018, it had inched past the Canadian dollar for the first time):

- Dollar: 61.8%

- Euro: 20.2%

- Japanese yen: 5.2%, up from 3.6% in 2014.

- UK pound sterling, at 4.5%.

- Chinese renminbi: 1.95% (record)

- Canadian Dollar: 1.92%

- Australian dollar: 1.7%

- Swiss franc: 0.15%

- Other: 2.45%

The share of these currencies is based on “allocated” reserves, as the IMF explains. Not all central banks disclose to the IMF how their total foreign exchange reserves are “allocated” among specific currencies. Back in 2014, only 59% of the foreign exchange reserves had been “allocated.” Since then, more and more central banks have disclosed to the IMF the allocation of their reserves. In Q1 2019, allocated reserves reached 94%. But the IMF does not publish the central banks individual holdings.

The theory that refuses to do die is that the US, as the country with “the” global reserve currency, “must have” a large trade deficit with the rest of the world. True, the US has a huge trade deficit with the rest of the world. But this “must have” is disproven by the euro, the second largest reserve currency: The Eurozone has a massive trade surplus with the rest of the world, proving that a major reserve currency can be backed by a trade surplus. And the yen, the third largest reserve currency, is backed by Japan’s large trade surplus.

The relationship would be the other way around. The fact that the dollar is the largest reserve currency (and the largest international funding currency) permits the US to easily fund its trade deficits. Countries that benefit from their trade surpluses with the US encourage this. They fear that if the dollar were knocked off its perch, the US could no longer fund those trade deficits, and in turn, these exporting countries could no longer run these big surpluses with the US, thus harming their own economies. So knocking the dollar off its perch would get complicated for other countries in a hurry.

Loading...