CrowdStrikeOut: Mueller’s Own Report Undercuts Its Core Russia-Meddling Claims

by Aaron Mate, Ron Paul Institute:

At a May press conference capping his tenure as special counsel, Robert Mueller emphasized what he called “the central allegation” of the two-year Russia probe. The Russian government, Mueller sternly declared, engaged in “multiple, systematic efforts to interfere in our election, and that allegation deserves the attention of every American.” Mueller’s comments echoed a January 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment (ICA) asserting with “high confidence” that Russia conducted a sweeping 2016 election influence campaign. “I don’t think we’ve ever encountered a more aggressive or direct campaign to interfere in our election process,” then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told a Senate hearing.

At a May press conference capping his tenure as special counsel, Robert Mueller emphasized what he called “the central allegation” of the two-year Russia probe. The Russian government, Mueller sternly declared, engaged in “multiple, systematic efforts to interfere in our election, and that allegation deserves the attention of every American.” Mueller’s comments echoed a January 2017 Intelligence Community Assessment (ICA) asserting with “high confidence” that Russia conducted a sweeping 2016 election influence campaign. “I don’t think we’ve ever encountered a more aggressive or direct campaign to interfere in our election process,” then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper told a Senate hearing.

While the 448-page Mueller report found no conspiracy between Donald Trump’s campaign and Russia, it offered voluminous details to support the sweeping conclusion that the Kremlin worked to secure Trump’s victory. The report claims that the interference operation occurred “principally” on two fronts: Russian military intelligence officers hacked and leaked embarrassing Democratic Party documents, and a government-linked troll farm orchestrated a sophisticated and far-reaching social media campaign that denigrated Hillary Clinton and promoted Trump.

But a close examination of the report shows that none of those headline assertions are supported by the report’s evidence or other publicly available sources. They are further undercut by investigative shortcomings and the conflicts of interest of key players involved:

– The report uses qualified and vague language to describe key events, indicating that Mueller and his investigators do not actually know for certain whether Russian intelligence officers stole Democratic Party emails, or how those emails were transferred to WikiLeaks.

– The report’s timeline of events appears to defy logic. According to its narrative, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange announced the publication of Democratic Party emails not only before he received the documents but before he even communicated with the source that provided them.

– There is strong reason to doubt Mueller’s suggestion that an alleged Russian cutout called Guccifer 2.0 supplied the stolen emails to Assange.

– Mueller’s decision not to interview Assange – a central figure who claims Russia was not behind the hack – suggests an unwillingness to explore avenues of evidence on fundamental questions.

– US intelligence officials cannot make definitive conclusions about the hacking of the Democratic National Committee computer servers because they did not analyze those servers themselves. Instead, they relied on the forensics of CrowdStrike, a private contractor for the DNC that was not a neutral party, much as “Russian dossier” compiler Christopher Steele, also a DNC contractor, was not a neutral party. This puts two Democrat-hired contractors squarely behind underlying allegations in the affair – a key circumstance that Mueller ignores.

– Further, the government allowed CrowdStrike and the Democratic Party’s legal counsel to submit redacted records, meaning CrowdStrike and not the government decided what could be revealed or not regarding evidence of hacking.

– Mueller’s report conspicuously does not allege that the Russian government carried out the social media campaign. Instead it blames, as Mueller said in his closing remarks, “a private Russian entity” known as the Internet Research Agency (IRA).

– Mueller also falls far short of proving that the Russian social campaign was sophisticated, or even more than minimally related to the 2016 election. As with the collusion and Russian hacking allegations, Democratic officials had a central and overlooked hand in generating the alarm about Russian social media activity.

None of this means that the Mueller report’s core finding of “sweeping and systematic” Russian government election interference is necessarily false. But his report does not present sufficient evidence to substantiate it. This shortcoming has gone overlooked in the partisan battle over two more highly charged aspects of Mueller’s report: potential Trump-Russia collusion and Trump’s potential obstruction of the resulting investigation. As Mueller prepares to testify before House committees later this month, the questions surrounding his claims of a far-reaching Russian influence campaign are no less important. They raise doubts about the genesis and perpetuation of Russiagate and the performance of those tasked with investigating it.

Uncertainty Over Who Stole the Emails

The Mueller report’s narrative of Russian hacking and leaking was initially laid out in a July 2018 indictment of 12 Russian intelligence officers and is detailed further in the report. According to Mueller, operatives at Russia’s main intelligence agency, the GRU, broke into Clinton campaign Chairman John Podesta’s emails in March 2016. The hackers infiltrated Podesta’s account with a common tactic called spear-phishing, duping him with a phony security alert that led him to enter his password. The GRU then used stolen Democratic Party credentials to hack into the DNC and Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) servers beginning in April 2016. Beginning in June 2016, the report claims, the GRU created two online personas, “DCLeaks” and “Guccifer 2.0,” to begin releasing the stolen material. After making contact later that month, Guccifer 2.0 apparently transferred the DNC emails to the whistleblowing, anti-secrecy publisher WikiLeaks, which released the first batch on July 22 ahead of the Democratic National Convention.

The report presents this narrative with remarkable specificity: It describes in detail how GRU officers installed malware, leased US-based computers, and used cryptocurrencies to carry out their hacking operation. The intelligence that caught the GRU hackers is portrayed as so invasive and precise that it even captured the keystrokes of individual Russian officers, including their use of search engines.

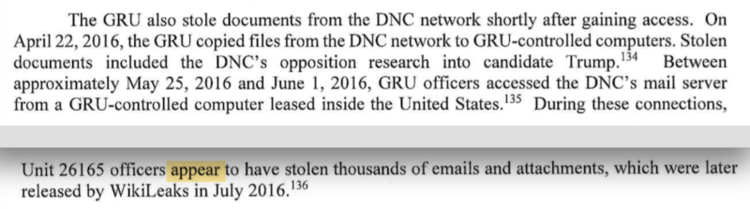

In fact, the report contains crucial gaps in the evidence that might support that authoritative account. Here is how it describes the core crime under investigation, the alleged GRU theft of DNC emails:

Between approximately May 25, 2016 and June 1, 2016, GRU officers accessed the DNC’s mail server from a GRU-controlled computer leased inside the United States. During these connections, Unit 26165 officers appear to have stolen thousands of emails and attachments, which were later released by WikiLeaks in July 2016. [Italics added for emphasis.]

The report’s use of that one word, “appear,” undercuts its suggestions that Mueller possesses convincing evidence that GRU officers stole “thousands of emails and attachments” from DNC servers. It is a departure from the language used in his July 2018 indictment, which contained no such qualifier:

“It’s certainly curious as to why this discrepancy exists between the language of Mueller’s indictment and the extra wiggle room inserted into his report a year later,” says former FBI Special Agent Coleen Rowley. “It may be an example of this and other existing gaps that are inherent with the use of circumstantial information. With Mueller’s exercise of quite unprecedented (but politically expedient) extraterritorial jurisdiction to indict foreign intelligence operatives who were never expected to contest his conclusory assertions in court, he didn’t have to worry about precision. I would guess, however, that even though NSA may be able to track some hacking operations, it would be inherently difficult, if not impossible, to connect specific individuals to the computer transfer operations in question.”

Read More @ RonPaulInstitute.org

Loading...