Trump’s ‘Thatcher Effect’: Obstacle to White Nationalism?, by Andrew Joyce

“While anti-fascists had eroded the organisational capacity of the National Front in the late 1970s, Margaret Thatcher had stolen their ideological clothing. As prime minister, she had successfully held together a coalition of support with her blend of jingoism and watered-down Powellism.

Daniel Trilling, Bloody Nasty People: The Rise of Britain’s Far Right (2012)

A rising White Nationalist movement that is somehow stunted in what should be its greatest moment of opportunity. A politically incorrect candidate for office, seemingly unafraid to discuss immigration, and who uses controversial rhetoric touching on race to attract mass support and move victoriously into government. An anti-fascist and left-liberal coalition driven to apoplexy by the repeated intrusion of “racist” arguments and ideas into the national discourse. And a mass influx of coloured migration that somehow continues unabated, perhaps even getting worse. This would be a useful and accurate summary of Donald Trump’s first term in office, which continues to frustrate and confuse those looking for tangible results. As discussions continue on Trump’s putative utility for the anti-immigration cause and on the alternative possibilities of “accelerationism” under a radical left-wing Democrat government, the following essay attempts to offer some advice and lessons from history — a relatively recent history, and one in which all of the important aspects of the Trump phenomenon listed above can be clearly seen. As will be demonstrated from the example of Margaret Thatcher and Britain’s National Front, it is argued here that Trump is an obstacle, and not the way, to the advancement of the Dissident Right.

A Movement on the Rise

The years 2014–16 may in some sense be regarded as a watershed in the recent history of Dissident Right ideas in the United States, and yet they were truly dwarfed by the progress of the Dissident Right in 1970s Britain. Founded in 1967 from a union of the British National Party and the League of Empire Loyalists (and later, the Greater Britain Movement), the National Front was a vehicle for racial thinking and anti-immigration viewpoints at a time when Britain was being swamped by successive floods of coloured migrants from former British colonies. Much like today’s political context, there was a relative neglect of immigration and race-related issues by the mainstream political parties. In yet another important similarity, British industry was beginning to undergo dramatic changes, with the emergence of increasingly troubled and alienated classes of Whites forced to live alongside growing Black and Pakistani enclaves. Simmering inter-racial tensions were being managed, barely, via the gagging of Whites under an increasing number of “race relations” laws, devised almost exclusively by a body of Jewish lawyers. The National Front was able to exploit this context and force its way into the political arena, taking voters from both the Conservative Party and the Labour Party throughout the 1970s. During the period 1972 to 1974, the Front boasted an active and paying membership somewhere between 14,000 and 20,000, and achieved advancement during local elections in 1973, 1976, and 1977. Its electoral influence has been described by scholars as “significant,” and its cultural impact was such that every voter in Britain knew exactly what the movement was, as well as the basic thrust of its ideological trajectory. It was a movement on the rise, and confidence was high.

A Politically Incorrect Leader

All this changed in 1978, at a moment when some thought the National Front had made a major ideological breakthrough. In late 1977 and early 1978, the Conservative Party and the Labour Party were roughly equal in the polls. The Labour Party was faltering under the weak leadership of Prime Minister James Callaghan, and had endured intense criticism for successive waves of industrial strikes, race riots, and a resurgence of ethno-religious violence in Northern Ireland. But the Conservative Party in opposition elicited an apathetic response from voters, as the impression grew that both political parties were equally flawed and unable to meet contemporary challenges. The real breakthrough for the Conservatives came due to a combination of severe strikes under Callaghan (“The Winter of Discontent”) and, perhaps even more importantly, a game-changing interview given by Thatcher (then Leader of the Opposition) to the primetime show World in Action in February 1978. In the interview, during which she was asked about the growth of the National Front, Thatcher remarked:

We are a British nation with British characteristics. Every nation can take some minorities, and in many ways they add to the richness and variety of this country. But the moment a minority threatens to become a big one, people get frightened.

Thatcher then indicated that a Conservative government would “limit all immigration.” The effect of these statements was immediate. Scholar E.A. Reitan points out that, “almost immediately the Conservatives shot up 10 percent in the polls,” while Thatcher biographer Robin Harris records that “immediately after the interview the Tories were eleven points ahead.” Aware of the success of the comments, Thatcher reiterated the same sentiments in a February 1979 interview with The Observer in which she stated:

I am the first to admit it is not easy to get clear figures from the Home Office about immigration, but there was a committee which looked at it and said that if we went on as we are then by the end of the century there would be four million people of the new Commonwealth or Pakistan here. Now, that is an awful lot and I think it means that people are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture and, you know, the British character has done so much for democracy, for law and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in. So, if you want good race relations, you have got to allay peoples’ fears on numbers.

Three months later, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister after the Conservatives gained 63 seats in Parliament and moved into government.

A Left in Panic

The Left were incensed by Thatcher’s comments, with much commentary later mirrored in hysterical reactions to Trump’s election campaign, and especially some of his statements before and after Charlottesville. Labour Home Secretary Merlyn Rees responded to the 1978 interview by arguing that Thatcher had “moved towards the attitudes and policies of the National Front” and was “making respectable racial hatred and inciting the threats to public order that we have seen in some of our towns and cities where there is an immigrant population.” Another M.P. accused Thatcher of “giving aid and comfort to the National Front.” All of this of course heavily prefigures the accusation that Trump “energised” the Alt-Right.

Promises Unfulfilled

The truth, of course, was that Thatcher was an unmitigated disaster for the National Front and the cause of racial nationalism more generally, and only time will tell how beneficial or harmful Trump will be to the American movement. It’s crucial to note that at no stage did Thatcher “elaborate on the policy changes which the party would make,” and no cast-iron procedures were outlined beyond a declaration that immigration would be in all cases “limited.” Thatcher’s statements relating to immigration were essentially her version of Trump’s “Wall” — specific enough to attract votes, and yet sufficiently open to interpretation and evasion to confound the support base. Biographer Robin Harris points out that there was no “end to immigration” under Thatcher, and that she personally played a part in the dropping of suggestions like a migrant register and migrant quotas at the proposal stage.

Despite the lack of progress, Thatcher’s politics acted as a release valve for racial tension, permitting Whites to ostensibly vote in line with their ethnic interests while denying them tangible results and depressing their instinct for further action. Rob Witte remarks that “the 1979 general elections turned out to be a total disaster for the National Front, and the major reason for its electoral reverse clearly was Mrs. Thatcher’s public identification of the Conservative Party with a hard line on immigration.” The basic mechanism here is the fatal instinct for Dissident Right sympathisers in the electorate to push their votes away from ideological purity (the original, smaller radical party) and into what they see as a more likely channel for translating their views into policy (an established, major political party). In this instance, the “anti-immigration” Prime Minister had effectively killed the anti-immigration movement in Britain for a generation – until the stunning rise of the British National Party in the early 2000s and its demise, under the same process as Thatcher/National Front, with votes in this instance going to the fledgling UKIP of Nigel Farage.

Shill or Dupe?

A further interesting parallel to explore is the question of the extent to which Thatcher or Trump were/are knowing participants in the marginalisation of the Dissident Right. And, just as current opinion is split on Trump, scholarly opinion remains split on Thatcher. It’s her biographers who appear most willing to entertain the notion that she was sincere in her anti-immigration politics but was thwarted by the political context in which she operated. Harris, for example, argues:

Though her phrasing was clumsy, Mrs. Thatcher knew exactly what she was doing. She was convinced that her instincts reflected those of the majority. She was also sincere. She had sympathised with [Enoch] Powell when he was sacked for his speech on the subject in 1968.

Internal government memoranda between Thatcher and Home Secretary William Whitelaw, released to the public in 2009 and dated July 1979, also seem to confirm that Thatcher had at least some sense of racial feeling. For example, Thatcher said that there were already too many people coming into Britain, and that “with some exceptions there had been no humanitarian case for accepting 1.5 million immigrants from south Asia and elsewhere. It was essential to draw a line somewhere.” Whitelaw responded that refugees were a different matter than immigrants in general, and that according to letters he had received, opinion favoured the accepting of more of the Vietnamese refugees. Thatcher responded that “in her view all those who wrote letters in this sense should be invited to accept one into their homes … She thought it quite wrong that immigrants should be given council housing whereas white citizens were not.” Thatcher was also asked what the implications of such a move could be given that an exodus of the White population from Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe – was expected once majority rule was established. She made it clear, however, that she had “less objection to refugees such as Rhodesians, Poles and Hungarians, since they could more easily be assimilated into British society.”

But the greater weight of scholarly opinion has concluded that Thatcher was a political opportunist who had no abiding sympathy for the Dissident Right or its ideas, and that she was quite happy to exploit the concerns of the electorate simply in order to gain power. Nigel Copsey, perhaps the foremost scholar of the British Far Right, has described Thatcher’s 1978 rhetoric as little more than a “cynical adoption of the race-card.” Some have gone even further, implying a degree of deliberation and co-ordination in undermining the National Front. For example, Brian Harrison, an academic at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, has argued that the Conservative Party of the 1970s, and Thatcher herself, were heavily influenced by a cadre of Jewish intellectuals for whom any kind of racial-nationalist thinking would have been anathema. He continues:

By the late 1960s — particularly after Powell’s ‘rivers of blood’ speech on race at Birmingham in 1968 — some on the left feared that Conservative anti-socialism would take anti-intellectual, even fascist, directions. Far from it: the Conservative leadership after 1975 was populist, but not anti-intellectual. Instead, it mobilized one group of intellectuals against another. Still less was its impulse fascist. The party’s brief foray after 1978 into restricting immigration was designed to head off the National Front (then relatively active), not to assist it, and Thatcherism had many Jewish exponents. [emphasis added]

Making Jews and Israel Great Again

It’s curious that Harrison frames the relationship as Thatcherism having many Jewish exponents, because the main body of his article basically makes the argument that it was the other way around – that Thatcher was an exponent of Jewish ideas, especially the “pro-tolerance” Libertarian ideas of Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek (who although not Jewish surrounded himself with a Jewish intellectual milieu). In fact, Thatcher’s ideological affiliations to Jews were so intense that they’ve become the subject of a 2017 monograph, Margaret Thatcher – The Honorary Jew: How Britain’s Jews Helped Shape the Iron Lady and Her Beliefs, which explores how she was surrounded by a cadre of Jewish advisors like Nigel Lawson, Malcolm Rifkind, David Young, Alfred Sherman, and Stephen Sherbourne . One of Thatcher’s closest political colleagues (she would later describe him as her “closest political friend”) was the Jewish Keith Joseph (1918-1994), a kind of Kushner to her Trump, and author of an Oxford thesis on “tolerance.” Joseph is even described on Wikipedia as the “key influence in the creation of what came to be known as Thatcherism.” Thatcherism was of course a form of distilled Jewish Libertarianism, a political-economic system masterfully denounced by Brenton Sanderson:

Free markets advance the interests of Jews through imposing an impersonal economic discipline on non-Jews through which their ethnocentricity and anti-Semitic prejudice can be circumvented. … Jews have indeed prospered under the conditions of free market capitalism among often hostile majority European-derived populations. … Jews, even in the freest of markets, are notorious for developing and using ethnic monopolies. … Accordingly, the free-market libertarian agenda, when promoted in the context of a society that is multi-racial, and where some racial groups exceed Whites in the degree of their ethnocentricity, may not promote the group evolutionary interests of Whites in enhancing their access to resources and reproductive success.

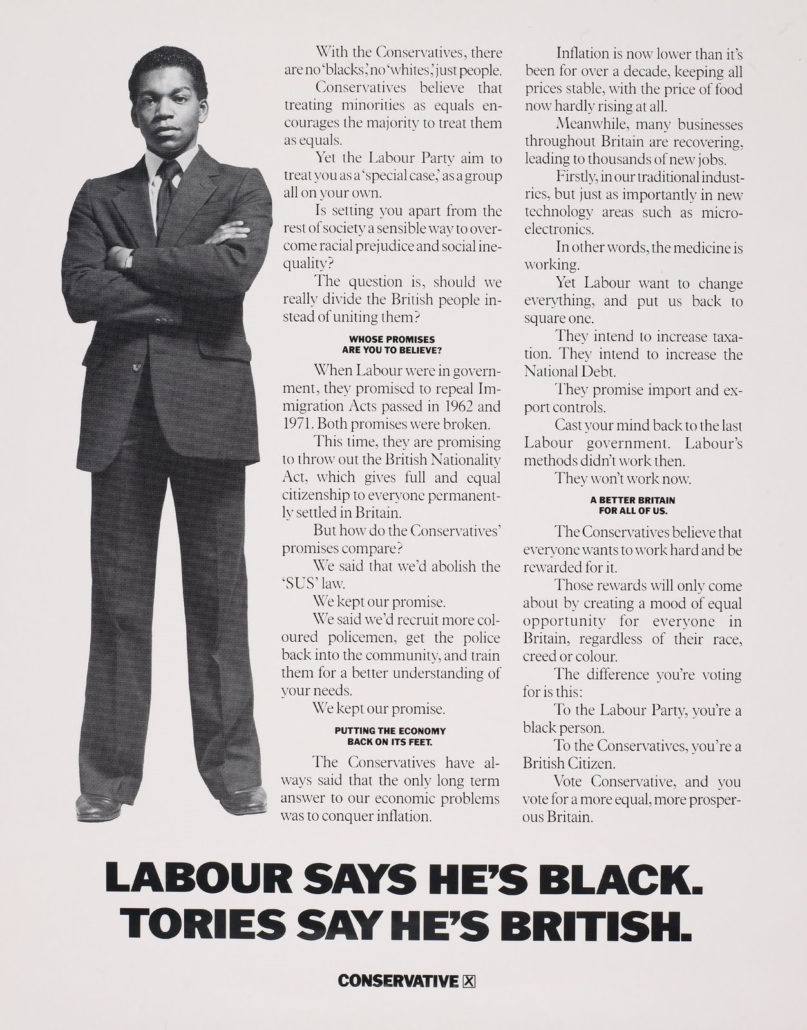

As such, the “right wing” political and economic philosophy of Thatcher and Joseph was perfectly happy with non-White migration as long as the immigrants were good free market capitalists. Harris, discussing Thatcher’s attitudes to Enoch Powell by the 1970s, remarks that “She no longer agreed with him, if she ever had, about the Kenyan Asians who found sanctuary in Britain in 1972. She regarded them as industrious and and entrepreneurial, in fact model Thatcherites.”In fact, the Conservatives under Thatcher and Joseph introduced propaganda that portrayed beliefs in multicultural, multi-racial, free market populism as fundamentally British, a fact amply demonstrated by the debut of a 1983 election poster showing a Pakistani or an African together with the slogan “Labour Says He’s Black. Tories [Conservatives] say he’s British.” Such posters were paired with a manifesto that stated bluntly: “We are utterly opposed to racial discrimination wherever it occurs, and we are determined to see that there is real equality of opportunity. The Conservative Party is, and always has been, strongly opposed to unfairness, harassment and persecution whether it be inspired by racial, religious, or ideological motives.” It goes without saying that this kind of multicultural, multi-racial, free market populism is almost identical to that advanced by Trump, whose increasingly vacuous declamations on “The Wall” are only matched in frequency by his references to the Black employment rate [it’s now rising again].

A final parallel worth considering is Thatcher’s position on Israel. Even as Leader of the Opposition, on March 22 1977, Thatcher posed in an Israeli General’s anorak, complete with visible markings of rank, on an Israeli hilltop lookout post on the Golan Heights. She was there as part of a three-day “fact-finding” visit to Israel. Just as Israel currently enjoys a love affair with Trump, scholar Neill Lochery recalls that “Even at this early stage, Israel’s love affair with Thatcher was underway with the Israeli press and public paying a great deal more attention to her visit that those of most VIP.”Until this date, the British Foreign Office had been resolutely hostile to Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, who was involved in the brutal mutilation and murder of two British Army sergeants in 1947, as well as the 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel, during which 28 British citizens were killed. In the late 1970s, when a potential visit by Begin to London was discussed, a Foreign Office memo was circulated containing the words: “I hope we will firmly repel this viper from our bosom.” On May 23 1979, Begin entered Number 10 Downing Street as the guest of Margaret Thatcher, whose daughter had by now spent a summer on a Kibbutz and who was herself a regular supporter of the Finchley Anglo–Israel Friendship League.

Thatcher was seen by Jews and Israel almost as their “agent,” capable of overturning the moves of those opposed to Israel and asserting their will in government. Lochery discusses how Israel viewed the British Foreign Office as implacably hostile to their interests, but saw Thatcher as incredibly useful. When the nine members of the European Economic Community (EEC) tried to frame a common policy towards the Arab–Israeli conflict and agreed to talk of the right of the Palestinians to self-determination (The Venice Declaration of June 13 1980), “The Israelis were shocked by the Venice Declaration, although they blamed the Foreign Office for Britain’s part in it rather than Thatcher. On 15 June 1980, the Israeli Cabinet strongly criticised the declaration. In Britain, the local Jewish lobby was mobilised to persuade Thatcher, in effect, to overturn or ignore the declaration. From this point forward, the Israelis looked for allies within the EEC who could offer some type of shield against what it saw as further anti-Israeli moves within the community. Thatcher was clearly a figure that the Israelis saw as fulfilling such a role.” They were correct, and on May 24 1986, Thatcher became the first British prime minister to pay an official visit to Israel. She was welcomed by Shimon Peres, who said the strength of the Anglo–Israeli relationship had never been better.

Whither Trump?

It’s argued here that there are sufficient parallels between the historical example of Margaret Thatcher and the contemporary phenomenon of Donald Trump to merit serious consideration of the desirability of a continuance of the Trump presidency. The primary concern, in light of historical examples, should be that, contrary to hysterical media narratives, multicultural right-wing populism of the variety espoused by both Trump and Thatcher has a confounding rather than galvanising effect on the basic instinct of Whites to assert and pursue their interests. These approaches are typified by a lack of tangible results on the primary concern (immigration), which is often disguised by diversions into superficial, even puerile, jingoism and in some instances actual war (Falklands War for Thatcher, and the real possibility of Trump engaging in conflict in the Middle East). It is unfortunate that one of the major strengths of the Dissident Right (its focus on immigration as a White concern) is also a weakness in the sense that it is remarkably easy to water down, repackage, and market to the electorate. Nigel Copsey has argued that one of the reasons for the failure of the National Front was not only that Thatcher had essentially stolen its ideological basics, but that the Front itself had failed to “build an effective social movement space.” It is particularly alarming that the American Dissident Right of 2012–2016 really had developed an effective social movement space (albeit one that was in large part located online) but was still lulled into a position where its ideological basics were stolen, and its energy was drained or diverted. At the heart of the issue here is whether the Dissident Right influenced Trump, or whether the energy and points of policy inherent in the Dissident Right were diverted to a Trump campaign that will ultimately fail to deliver on anything except Jewish/Israeli interests.

Just prior to Trump’s election, I participated in a number of podcasts where I offered my tentative support to the Trump campaign but mentioned that Dissident Right groups always perform best against strongly Leftist governments. I expressed my concern that we might, under Trump, see a chilling effect on the Alt-Right and an emergence of the “Thatcher Effect.” I hesitated to elaborate then on what I meant because of the optimism, and because I wanted to believe, like everyone else, that the Wall would be built, that ICE would be conducting raids, and that Whites across America would get used to a harder rhetoric on race and immigration than they had hitherto been exposed to or permitted. But I write this elaboration on the “Thatcher Effect” in a different context entirely to that which was expected — a context of censorship and deplatforming, seemingly unstoppable migrant caravans, and a settlement in the Golan Heights named after Trump. If nothing else, I hope it’s food for thought.

Notes

J. Solomos, Race and Racism in Contemporary Britain (London: Macmillan, 1989), 132.

R. Garbaye, Getting Into Local Power: The Politics of Ethnic Minorities in British and French Cities (Oxford: Blackwell, 2005), 51.

R. Witte, Racist Violence and the State: a comparative analysis of Britain, France, and the Netherlands (London: Routledge, 2014), 54.

Ibid.

E. A. Reitan, The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, and the Transformation of Modern Britain, 1979-2001 (New York: Rowan and Littlefield, 2003), 22.

R. Harris, Not for Turning: The Life of Margaret Thatcher (London: Bantam Press, 2013), 144.

S. Taylor, The National Front in English Politics (London: Macmillan, 1989), 145.

Ibid.

Ibid.

R. Harris, Not for Turning: The Life of Margaret Thatcher (London: Bantam Press, 2013), 144.

R. Witte, Racist Violence and the State: a comparative analysis of Britain, France, and the Netherlands (London: Routledge, 2014), 54.

R. Harris, Not for Turning: The Life of Margaret Thatcher (London: Bantam Press, 2013), 143.

N. Copsey, Cultures of Post-War British Fascism (New York: Routledge, 2015), 66.

B. Harrison, ‘Mrs Thatcher and the Intellectuals,’ Twentieth Century British History, Vol. 5, No. 2, 1994, 206-45, (207).

Ibid, 209.

R. Harris, Not for Turning: The Life of Margaret Thatcher (London: Bantam Press, 2013), 143.

Z. Layton‐Henry (1983). ‘Immigration and race relations: Political aspects,’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 11(1-2), 109–116, (111).

Ibid.

N. Lochery (2010). ‘Debunking the Myths: Margaret Thatcher, the Foreign Office and Israel, 1979–1990.’ Diplomacy & Statecraft, 21(4), 690–706.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

N. Copsey, Cultures of Post-War British Fascism (New York: Routledge, 2015), 66.