Ron Unz • June 11, 2018 • 5,400 Words

www.invexnews.com/item-459521-american-pravda-understanding-world-war-ii-by-ron-unz

Print

American Pravda: Understanding World War II, by Ron Unz

In late 2006 I was approached by Scott McConnell, editor of The American Conservative (TAC), who told me that his small magazine was on the verge of closing without a large financial infusion. I’d been on friendly terms with McConnell since around 1999, and greatly appreciated that he and his TAC co-founders had been providing a focal point of opposition to America’s calamitous foreign policy of the early 2000s.

In late 2006 I was approached by Scott McConnell, editor of The American Conservative (TAC), who told me that his small magazine was on the verge of closing without a large financial infusion. I’d been on friendly terms with McConnell since around 1999, and greatly appreciated that he and his TAC co-founders had been providing a focal point of opposition to America’s calamitous foreign policy of the early 2000s.

In the wake of 9/11, the Israel-centric Neocons had somehow managed to seize control of the Bush Administration while also gaining complete ascendancy over America’s leading media outlets, purging or intimidating most of their critics. Although Saddam Hussein clearly had no connection to the attacks, his status as a possible regional rival to Israel had established him as their top target, and they soon began beating the drums for war, with America finally launching its disastrous invasion in February 2003.

Among print magazines, TAC stood almost alone in whole-hearted opposition to these policies, and had attracted considerable attention when Founding Editor Pat Buchanan published “Whose War?”, pointing the finger of blame directly at the Jewish Neocons responsible, a truth very widely recognized in political and media circles but almost never publicly voiced. David Frum, a leading promoter of the Iraq War, had almost simultaneously unleashed a National Review cover story denouncing as “unpatriotic”—and perhaps “anti-Semitic”—a very long list of conservative, liberal, and libertarian war critics, with Buchanan near the very top, and the controversy and name-calling continued for some time.

Given this recent history, I was concerned that TAC‘s disappearance might leave a dangerous political void, and being then in a relatively strong financial position, I agreed to rescue the magazine and become its new owner. Although I was much too preoccupied with my own software work to have any direct involvement, McConnell named me publisher, probably hoping to bind me to his magazine’s continuing survival and ensure future financial infusions. My title was purely a nominal one, and over the next few years, aside from writing additional checks my only involvement usually amounted to a five-minute phone call each Monday morning to see how things were going.

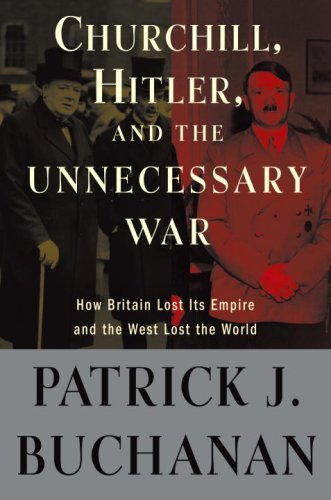

About a year after I began supporting the magazine, McConnell informed me that a major crisis was brewing. Although Pat Buchanan had severed his direct ties with the publication some years earlier, he was by far the best-known figure associated with TAC, so that it was still widely—if erroneously—known as “Pat Buchanan’s magazine.” But now McConnell had heard that Buchanan was planning to release a new book supposedly glorifying Adolf Hitler and denouncing America’s participation in the world war to defeat the Nazi menace. Promoting such bizarre beliefs would surely doom Buchanan’s career, but TAC was already under continuous attack by Jewish activists, and the resulting “Neo-Nazi” guilt by association might easily sink the magazine as well.

In desperation, McConnell had decided to protect his publication by soliciting a very hostile review by conservative historian John Lukacs, which would thereby insulate TAC from the looming disaster. Given my current role as TAC‘s funder and publisher, he naturally sought my approval in this harsh break with his own political mentor. I told him that the Buchanan book certainly sounded rather ridiculous and his own defensive strategy a pretty reasonable one, and I quickly returned to the problems I faced in my own all-consuming software project.

Although I’d been a little friendly with Buchanan for a dozen years or so, and greatly admired his courage in opposing the Neocons on foreign policy, I wasn’t too surprised to hear that he might be publishing a book promoting some rather strange ideas. Just a few years earlier, he’d released The Death of the West, which became an unexpected best-seller. After my friends at TAC had raved about its brilliance, I decided to read it for myself, and was greatly disappointed. Although Buchanan had generously quoted an excerpt from my own Commentary cover-story “California and the End of White America,” I felt that he’d completely misconstrued my meaning, and the book overall seemed a rather poorly-constructed and rhetorically right-wing treatment of the complex issues of immigration and race, topics upon which I’d been heavily focusing since the early 1990s. So under the circumstances, I was hardly surprised that the same author was now publishing some equally silly book about World War II, perhaps causing severe problems for his erstwhile TAC colleagues.

Months later, Buchanan’s history and the hostile TAC review both appeared, and as expected, a storm of controversy erupted. Mainstream publications had largely ignored the book, but it seemed to receive enormous praise from alternative writers, some of whom fiercely denounced TAC for having attacked it. Indeed, the response was so extremely one-sided that when McConnell discovered that a totally obscure blogger somewhere had agreed with his own negative appraisal, he immediately circulated those remarks in a desperate attempt at vindication. Longtime TAC contributors whose knowledge of history I much respected, including Eric Margolis and William Lind, had praised the book, so my curiosity finally got the better of me and I decided to order a copy and read it for myself.

I was quite surprised to discover a work very different from what I had expected. I had never paid much attention to twentieth century American history and my knowledge of European history in that same era was only slightly better, so my views were then mostly rather conventional, having been shaped by my History 101 courses and what I’d picked up in decades of reading my various newspapers and magazines. But within that framework, Buchanan’s history seemed to fit quite comfortably.

The first part of his volume provided what I had always considered the standard view of the First World War. In his account of events, Buchanan explained how the complex network of interlocking alliances had led to a giant conflagration even though none of the existing leaders had actually sought that outcome: a huge European powder-keg had been ignited by the spark of an assassination in Sarajevo.

But although his narrative was what I expected, he provided a wealth of interesting details previously unknown to me. Among other things, he persuasively argued that the German war-guilt was somewhat less than that of most of the other participants, also noting that despite the endless propaganda of “Prussian militarism,” Germany had not fought a major war in 43 years, an unbroken record of peace considerably better than that of most of its adversaries. Moreover, a secret military agreement between Britain and France had been a crucial factor in the unintended escalation, and even so, nearly half the British Cabinet had come close to resigning in opposition to the declaration of war against Germany, a possibility that which would have probably led to a short and limited conflict confined to the Continent. I’d also seldom seen emphasized that Japan had been a crucial British ally, and that the Germans probably would have won the war if Japan had fought on the other side.

However, the bulk of the book focused on the events leading up to the Second World War, and this was the portion that had inspired such horror in McConnell and his colleagues. Buchanan described the outrageous provisions of the Treaty of Versailles imposed upon a prostrate Germany, and the determination of all subsequent German leaders to redress it. But whereas his democratic Weimar predecessors had failed, Hitler had managed to succeed, largely through bluff, while also annexing German Austria and the German Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia, in both cases with the overwhelming support of their populations.

Buchanan documented this controversial thesis by drawing heavily upon numerous statements by leading contemporary political figures, mostly British, as well as the conclusions of highly-respected mainstream historians. Hitler’s final demand, that 95% German Danzig be returned to Germany just as its inhabitants desired, was an absolutely reasonable one, and only a dreadful diplomatic blunder by the British had led the Poles to refuse the request, thereby provoking the war. The widespread later claim that Hitler sought to conquer the world was totally absurd, and the German leader had actually made every effort to avoid war with Britain or France. Indeed, he was generally quite friendly towards the Poles and had been hoping to enlist Poland as a German ally against the menace of Stalin’s Soviet Union.

Although many Americans might have been shocked at this account of the events leading up to the outbreak of the Second World War, Buchanan’s narrative accorded reasonably well with my own impression of that period. As a Harvard freshman, I had taken an introductory history course, and one of the primary required texts on World War II had been that of A.J.P. Taylor, a renowned Oxford University historian. His famous 1961 work Origins of the Second World War had very persuasively laid out a case quite similar to that of Buchanan, and I’d never found any reason to question the judgment of my professors who had assigned it. So if Buchanan merely seemed to be seconding the opinions of a leading Oxford don and members of the Harvard history faculty, I couldn’t quite understand why his new book would be regarded as being beyond the pale.

Admittedly, Buchanan also included a very harsh critique of Winston Churchill, cataloging a long list of his supposedly disastrous policies and political reversals, and assigning him a good share of the blame for Britain’s involvement in both world wars, fateful decisions that consequently led to the collapse of the British Empire. But although my knowledge of Churchill was far too scanty to render a verdict, the case he made for the prosecution seemed reasonably strong. The Neocons already hated Buchanan and since they notoriously worshiped Churchill as a cartoon super-hero, any firestorm of criticism from those quarters would hardly be surprising. But the book overall seemed a very solid and interesting history, the best work by Buchanan that I had ever read, and I gently gave my favorable assessment to McConnell, who was obviously rather disappointed. Not long afterward, he decided to relinquish his role as TAC editor to Kara Hopkins, his longtime deputy, and the wave of vilification he had recently endured from many of his erstwhile Buchananite allies surely must have contributed to this.

Although my knowledge of the history of the Second World War was quite rudimentary back in 2008, over the decade that followed I embarked upon a great deal of reading in the history of that momentous era, and my preliminary judgment in the correctness of Buchanan’s thesis seemed strongly vindicated.

The recent 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the conflict that consumed so many tens of millions of lives naturally provoked numerous historical articles, and the resulting discussion led me to dig out my old copy of Taylor’s short volume, which I reread for the first time in nearly forty years. I found it just as masterful and persuasive as I had back in my college dorm room days, and the glowing cover-blurbs suggested some of the immediate acclaim the work had received. The Washington Post lauded the author as “Britain’s most prominent living historian,” World Politics called it “Powerfully argued, brilliantly written, and always persuasive,” The New Statesman, Britain leading leftist magazine, described it as “A masterpiece: lucid, compassionate, beautifully written,” and the august Times Literary Supplement characterized it as “simple, devastating, superlatively readable, and deeply disturbing.” As an international best-seller, it still surely ranks as Taylor’s most famous book, and I can easily understand why it was still on my college required reading list nearly two decades after its original publication.

Yet in revisiting Taylor’s ground-breaking study, I made a remarkable discovery. Despite all the international sales and critical acclaim, the book’s findings soon aroused tremendous hostility in certain quarters. Taylor’s lectures at Oxford had been enormously popular for a quarter century, but as a direct result of the controversy “Britain’s most prominent living historian” was summarily purged from the faculty not long afterwards. At the beginning of his first chapter, Taylor had noted how strange he found it that more than twenty years after the start of the world’s most cataclysmic war no serious history had been produced carefully analyzing the outbreak. Perhaps the retaliation that he encountered led him to better understand part of that puzzle.

Taylor was hardly alone in suffering such retribution. Indeed, as I have gradually discovered over the last decade or so, his fate seems to have been an exceptionally mild one, with his great existing stature partially insulting him from the backlash following his objective analysis of the historical facts. And such extremely serious professional consequences were especially common on our side of the Atlantic, where many of the victims lost their long-held media or academic positions, and permanently vanished from public view during the years surrounding World War II.

I had spent much of the 2000s producing a massive digitized archive containing the full contents of hundreds of America’s most influential periodicals from the last two centuries, a collection totaling many millions of articles. And during this process, I was repeatedly surprised to come across individuals whose enormous presence clearly marked them as among the leading public intellectuals of their day, but who had later disappeared so completely that I had scarcely ever been aware of their existence. I gradually began to recognize that our own history had been marked by an ideological Great Purge just as significant if less sanguinary than its Soviet counterpart. The parallels seemed eerie:

I sometimes imagined myself a little like an earnest young Soviet researcher of the 1970s who began digging into the musty files of long-forgotten Kremlin archives and made some stunning discoveries. Trotsky was apparently not the notorious Nazi spy and traitor portrayed in all the textbooks, but instead had been the right-hand man of the sainted Lenin himself during the glorious days of the great Bolshevik Revolution, and for some years afterward had remained in the topmost ranks of the Party elite. And who were these other figures—Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Rykov—who also spent those early years at the very top of the Communist hierarchy? In history courses, they had barely rated a few mentions, as minor Capitalist agents who were quickly unmasked and paid for their treachery with their lives. How could the great Lenin, father of the Revolution, have been such an idiot to have surrounded himself almost exclusively with traitors and spies?

But unlike their Stalinist analogs from a couple of years earlier, the American victims who disappeared around 1940 were neither shot nor Gulaged, but merely excluded from the mainstream media that defines our reality, thereby being blotted out from our memory so that future generations gradually forgot that they had ever lived.

A leading example of such a “disappeared” American was journalist John T. Flynn, probably almost unknown today but whose stature had once been enormous. As I wrote last year:

So imagine my surprise at discovering that throughout the 1930s he had been one of the single most influential liberal voices in American society, a writer on economics and politics whose status may have roughly approximated that of Paul Krugman, though with a strong muck-raking tinge. His weekly column in The New Republic allowed him to serve as a lodestar for America’s progressive elites, while his regular appearances in Colliers, an illustrated mass circulation weekly reaching many millions of Americans, provided him a platform comparable to that of an major television personality in the later heyday of network TV.

To some extent, Flynn’s prominence may be objectively quantified. A few years ago, I happened to mention his name to a well-read and committed liberal born in the 1930s, and she unsurprisingly drew a complete blank, but wondered if he might have been a little like Walter Lippmann, the very famous columnist of that era. When I checked, I saw that across the hundreds of periodicals in my archiving system, there were just 23 articles by Lippmann from the 1930s but fully 489 by Flynn.

An even stronger American parallel to Taylor was that of historian Harry Elmer Barnes, a figure almost unknown to me, but in his day an academic of great influence and stature:

Imagine my shock at later discovering that Barnes had actually been one of the most frequent early contributors to Foreign Affairs, serving as a primary book reviewer for that venerable publication from its 1922 founding onward, while his stature as one of America’s premier liberal academics was indicated by his scores of appearances in The Nation and The New Republic throughout that decade. Indeed, he is credited with having played a central role in “revising” the history of the First World War so as to remove the cartoonish picture of unspeakable German wickedness left behind as a legacy of the dishonest wartime propaganda produced by the opposing British and American governments. And his professional stature was demonstrated by his thirty-five or more books, many of them influential academic volumes, along with his numerous articles in The American Historical Review, Political Science Quarterly, and other leading journals.

A few years ago I happened to mention Barnes to an eminent American academic scholar whose general focus in political science and foreign policy was quite similar, and yet the name meant nothing. By the end of the 1930s, Barnes had become a leading critic of America’s proposed involvement in World War II, and was permanently “disappeared” as a consequence, barred from all mainstream media outlets, while a major newspaper chain was heavily pressured into abruptly terminating his long-running syndicated national column in May 1940.

Many of Barnes’ friends and allies fell in the same ideological purge, which he described in his own writings and which continued after the end of the war:

Over a dozen years after his disappearance from our national media, Barnes managed to publish Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace, a lengthy collection of essays by scholars and other experts discussing the circumstances surrounding America’s entrance into World War II, and have it produced and distributed by a small printer in Idaho. His own contribution was a 30,000 word essay entitled “Revisionism and the Historical Blackout” and discussed the tremendous obstacles faced by the dissident thinkers of that period.

The book itself was dedicated to the memory of his friend, historian Charles A. Beard. Since the early years of the 20th century, Beard had ranked as an intellectual figure of the greatest stature and influence, co-founder of The New School in New York and serving terms as president of both The American Historical Association and The American Political Science Association. As a leading supporter of the New Deal economic policies, he was overwhelmingly lauded for his views.

Yet once he turned against Roosevelt’s bellicose foreign policy, publishers shut their doors to him, and only his personal friendship with the head of the Yale University Press allowed his critical 1948 volume President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War, 1941 to even appear in print. Beard’s stellar reputation seems to have begun a rapid decline from that point onward, so that by 1968 historian Richard Hofstadter could write: “Today Beard’s reputation stands like an imposing ruin in the landscape of American historiography. What was once the grandest house in the province is now a ravaged survival”. Indeed, Beard’s once-dominant “economic interpretation of history” might these days almost be dismissed as promoting “dangerous conspiracy theories,” and I suspect few non-historians have even heard of him.

Another major contributor to the Barnes volume was William Henry Chamberlin, who for decades had been ranked among America’s leading foreign policy journalists, with more than 15 books to his credit, most of them widely and favorably reviewed. Yet America’s Second Crusade, his critical 1950 analysis of America’s entry into World War II, failed to find a mainstream publisher, and when it did appear was widely ignored by reviewers. Prior to its publication, his byline had regularly run in our most influential national magazines such as The Atlantic Monthly and Harpers. But afterward, his writing was almost entirely confined to small circulation newsletters and periodicals, appealing to narrow conservative or libertarian audiences.

In these days of the Internet, anyone can easily establish a website to publish his views, thus making them immediately available to everyone in the world. Social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter can bring interesting or controversial material to the attention of millions with just a couple of mouse-clicks, completely bypassing the need for the support of establishmentarian intermediaries. It is easy for us to forget just how extremely challenging the dissemination of dissenting ideas remained back in the days of print, paper, and ink, and recognize that an individual purged from his regular outlet might require many years to regain any significant foothold for the distribution of his work.

British writers had faced similar ideological perils year before A.J.P. Taylor ventured into those troubled waters, as a distinguished British naval historian discovered in 1953:

The author of Unconditional Hatred was Captain Russell Grenfell, a British naval officer who had served with distinction in the First World War, and later helped direct the Royal Navy Staff College, while publishing six highly-regarded books on naval strategy and serving as the Naval Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph. Grenfell recognized that great quantities of extreme propaganda almost inevitably accompany any major war, but with several years having passed since the close of hostilities, he was growing concerned that unless an antidote were soon widely applied, the lingering poison of such wartime exaggerations might threaten the future peace of Europe.

His considerable historical erudition and his reserved academic tone shine through in this fascinating volume, which focuses primarily upon the events of the two world wars, but often contains digressions into the Napoleonic conflicts or even earlier ones. One of the intriguing aspects of his discussion is that much of the anti-German propaganda he seeks to debunk would today be considered so absurd and ridiculous it has been almost entirely forgotten, while much of the extremely hostile picture we currently have of Hitler’s Germany receives almost no mention whatsoever, possibly because it had not yet been established or was then still considered too outlandish for anyone to take seriously. Among other matters, he reports with considerable disapproval that leading British newspapers had carried headlined articles about the horrific tortures that were being inflicted upon German prisoners at war crimes trials in order to coerce all sorts of dubious confessions out of them.

Some of Grenfell’s casual claims do raise doubts about various aspects of our conventional picture of German occupation policies. He notes numerous stories in the British press of former French “slave-laborers” who later organized friendly post-war reunions with their erstwhile German employers. He also states that in 1940 those same British papers had reported the absolutely exemplary behavior of German soldiers toward French civilians, though after terroristic attacks by Communist underground forces provoked reprisals, relations often grew much worse.

Most importantly, he points out that the huge Allied strategic bombing campaign against French cities and industry had killed huge numbers of civilians, probably far more than had ever died at German hands, and thereby provoked a great deal of hatred as an inevitable consequence. At Normandy he and other British officers had been warned to remain very cautious among any French civilians they encountered for fear they might be subject to deadly attacks.

Although Grenfell’s content and tone strike me as exceptionally even-handed and objective, others surely viewed his text in a very different light. The Devin-Adair jacket-flap notes that no British publisher was willing to accept the manuscript, and when the book appeared no major American reviewer recognized its existence. Even more ominously, Grenfell is described as having been hard at work on a sequel when he suddenly died in 1954 of unknown causes, and his lengthy obituary in the London Times gives his age as 62.

Another top contemporary observer from that era provides a portrayal of France during World War II that is diametrically opposed to that of today’s widely-accepted narrative:

On French matters, Grenfell provides several extended references to a 1952 book entitled France: The Tragic Years, 1939-1947 by Sisley Huddleston, an author totally unfamiliar to me, and this whet my curiosity. One helpful use of my content-archiving system is to easily provide the proper context for long-forgotten writers, and Huddleston’s scores of appearances in The Atlantic Monthly, The Nation, and The New Republic, plus his thirty well-regarded books on France, seem to confirm that he spent decades as one of the leading interpreters of France to educated American and British readers. Indeed, his exclusive interview with British Prime Minister Lloyd George at the Paris Peace Conference became an international scoop. As with so many other writers, after World War II his American publisher necessarily became Devin-Adair, which released a posthumous 1955 edition of his book. Given his eminent journalistic credentials, Huddleston’s work on the Vichy period was reviewed in American periodicals, although in rather cursory and dismissive fashion, and I ordered a copy and read it.

I cannot attest to the correctness of Huddleston’s 350 page account of France during the war years and immediately after, but as a very distinguished journalist and longtime observer who was an eyewitness to the events he describes, writing at a time when the official historical narrative had not yet hardened into concrete, I do think that his views should be taken quite seriously. Huddleston’s personal circle certainly extended quite high, with former U.S. Ambassador William Bullitt being one of his oldest friends. And without doubt Huddleston’s presentation is radically different from the conventional story I had always heard.

As Huddleston describes things, the French army collapsed in May of 1940, and the government desperately recalled Petain, then in his mid-80s and the country’s greatest war hero, from his posting as the Ambassador to Spain. Soon he was asked by the French President to form a new government and arrange an armistice with the victorious Germans, and this proposal received near-unanimous support from France’s National Assembly and Senate, including the backing of virtually all the leftist parliamentarians. Petain achieved this result, and another near-unanimous vote of the French parliament then authorized him to negotiate a full peace treaty with Germany, which certainly placed his political actions on the strongest possible legal basis. At that point, almost everyone in Europe believed that the war was essentially over, with Britain soon to make peace.

While Petain’s fully-legitimate French government was negotiating with Germany, a small number of diehards, including Col. Charles de Gaulle, deserted from the army and fled aboard, declaring that they intended to continue the war indefinitely, but they initially attracted minimal support or attention. One interesting aspect of the situation was that De Gaulle had long been one of Petain’s leading proteges, and once his political profile began rising a couple of years later, there were often quiet speculations that he and his old mentor had arranged a “division of labor,” with the one making an official peace with the Germans while the other left to become the center of overseas resistance in the uncertain event that different opportunities arose.

Although Petain’s new French government guaranteed that its powerful navy would never be used against the British, Churchill took no chances, and quickly launched an attack on the fleet of its erstwhile ally, whose ships were already disarmed and helplessly moored in port, sinking most of them, and killing up to 2,000 Frenchmen in the process. This incident was not entirely dissimilar to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the following year, and rankled the French for many years to come.

Huddleston then spends much of the book discussing the complex French politics of the next few years, as the war unexpectedly continued, with Russia and America eventually joining the Allied cause, greatly raising the odds against a German victory. During this period, the French political and military leadership performed a difficult balancing act, resisting German demands on some points and acquiescing to them on others, while the internal Resistance movement gradually grew, attacking German soldiers and provoking harsh German reprisals. Given my lack of expertise, I cannot really judge the accuracy of his political narrative, but it seems quite realistic and plausible to me, though specialists might surely find fault.

However, the most remarkable claims in Huddleston’s book come towards the end, as he describes what eventually became known as “the Liberation of France” during 1944-45 when the retreating German forces abandoned the country and pulled back to their own borders. Among other things, he suggests that the number of Frenchmen claiming “Resistance” credentials grew as much as a hundred-fold once the Germans had left and there was no longer any risk in adopting that position.

And at that point, enormous bloodshed soon began, by far the worst wave of extra-judicial killings in all of French history. Most historians agree that around 20,000 lives were lost in the notorious “Reign of Terror” during the French Revolution and perhaps 18,000 died during the Paris Commune of 1870-71 and its brutal suppression. But according to Huddleston the American leaders estimated there were at least 80,000 “summary executions” in just the first few months after Liberation, while the Socialist Deputy who served as Interior Minister in March 1945 and would have been in the best position to know, informed De Gaulle’s representatives that 105,000 killings had taken place just from August 1944 to March 1945, a figure that was widely quoted in public circles at the time.

Since a large fraction of the entire French population had spent years behaving in ways that now suddenly might be considered “collaborationist,” enormous numbers of people were vulnerable, even at risk of death, and they sometimes sought to save their own lives by denouncing their acquaintances or neighbors. Underground Communists had long been a major element of the Resistance, and many of them eagerly retaliated against their hated “class enemies,” while numerous individuals took the opportunity to settle private scores. Another factor was that many of the Communists who had fought in the Spanish Civil War, including thousands of the members of the International Brigades, had fled to France after their military defeat in 1938, and now often took the lead in enacting vengeance against the same sort of conservative forces who had previously vanquished them in their own country.

Although Huddleston himself was an elderly, quite distinguished international journalist with very highly placed American friends, and he had performed some minor services on behalf of the Resistance leadership, he and his wife narrowly escaped summary execution during that period, and he provides a collection of the numerous stories he heard of less fortunate victims. But what appears to have been by far the worst sectarian bloodshed in French history has been soothingly rechristened “the Liberation” and almost entirely removed from our historical memory, except for the famously shaved heads of a few disgraced women. These days Wikipedia constitutes the congealed distillation of our Official Truth, and its entry on those events puts the death toll at barely one-tenth the figures quoted by Huddleston, but I find him a far more credible source.

We may easily imagine that some prominent and highly-regarded individual at the peak of his career and public influence might suddenly take leave of his senses and begin promoting eccentric and erroneous theories, thereby ensuring his downfall. Under such circumstances, his claims may be treated with great skepticism and perhaps simply disregarded.

But when the number of such very reputable yet contrary voices becomes sufficiently large and the claims they make seem generally consistent with each other, we can no longer casually dismiss their critiques. Their committed stance on these controversial matters had proved fatal to their continued public standing, and although they must have recognized these likely consequences, they nonetheless followed that path, even going to the trouble of writing lengthy books presenting their views, and seeking out some publisher somewhere who was willing to release these.

John T. Flynn, Harry Elmer Barnes, Charles Beard, William Henry Chamberlin, Russell Grenfell, Sisley Huddleston, and numerous other scholars and journalists of the highest caliber and reputation all told a rather consistent story of the Second World War but one at total variance with that of today’s established narrative, and they did so at the cost of destroying their careers. A decade or two later, renowned historian A.J.P. Taylor reaffirmed this same basic narrative, and was purged from Oxford as a consequence. I find it very difficult to explain the behavior of all these individuals unless they were presenting a truthful account.

If a ruling political establishment and its media organs offer lavish rewards of funding, promotion, and public acclaim to those who endorse its party-line propaganda while casting into outer darkness those who dissent, the pronouncements of the former should be viewed with considerable suspicion. Barnes popularized the phrase “court historians” to describe these disingenuous and opportunistic individuals who follow the prevailing political winds, and our present-day media outlets are certainly replete with such types.

A climate of serious intellectual repression greatly complicates our ability to uncover the events of the past. Under normal circumstances, competing claims can be weighed in the give-and-take of public or scholarly debate, but this obviously becomes impossible if the subjects being discussed are forbidden ones. Moreover, writers of history are human beings, and if they have been purged from their prestigious positions, blacklisted from public venues, and even cast into poverty, we should hardly be surprised if they sometimes grow angry and bitter at their fate, perhaps reacting in ways that their enemies may later use to attack their credibility.

A.J.P. Taylor lost his Oxford post for publishing his honest analysis of the origins of World War II, but his enormous previous stature and the widespread acclaim his book had received seemed to protect him from further damage, and the work itself soon became recognized as a great classic, remaining permanently in print and later gracing the required reading lists of our most elite universities. However, others who delved into those same troubled waters were much less fortunate.

The same year that Taylor’s book appeared so did a work covering much the same ground by a fledgling scholar named David L. Hoggan. Hoggan had earned his 1948 Ph.D. in diplomatic history at Harvard under Prof. William Langer, one of the towering figures in that field, and his maiden work The Forced War was a direct outgrowth of his doctoral dissertation. While Taylor’s book was fairly short and mostly based upon public sources and some British documents, Hoggan’s volume was exceptionally long and detailed, running nearly 350,000 words including references, and drew upon his many years of painstaking research in the newly available governmental archives of Poland and Germany. Although the two historians were fully in accord that Hitler had certainly not intended the outbreak of World War II, Hoggan argued that various powerful individuals within the British government had deliberately worked to provoke the conflict, thereby forcing the war upon Hitler’s Germany just as his title suggested.

Given the highly controversial nature of Hoggan’s conclusions and his lack of previous scholarly accomplishments, his huge work only appeared in a German edition, where it quickly became a hotly-debated bestseller in that language. As a junior academic, Hoggan was quite vulnerable to the enormous pressure and opprobrium he surely must have faced. He seems to have quarreled with Barnes, his revisionist mentor, while his hopes of arranging an English language edition via a small American publisher soon dissipated. Perhaps as a consequence, the embattled young scholar later suffered a series of nervous breakdowns, and by the end of the 1960s he had resigned his position at San Francisco State College, the last serious academic position he was ever to hold. He subsequently earned his living as a research fellow at a small libertarian thinktank, and after it folded taught at a local junior college, hardly the expected professional trajectory of someone who had begun with such auspicious Harvard credentials.

In 1984 an English version of his major work was finally about to be released when the facilities of its small revisionist publisher in the Los Angeles area were fire-bombed and totally destroyed by Jewish militants, thus obliterating the plates and all existing stock. Living in total obscurity, Hoggan himself died of a heart-attack in 1988, aged 65, and the following year an English version of his work finally appeared, nearly three decades after originally produced, with the scarce surviving copies today being extremely rare and costly. However, a PDF version lacking all footnotes is available on the Internet, and I have now added Hoggan’s volume to my collection of HTML Books, finally making it conveniently available to a broader audience almost six decades after it was completed.

When Peaceful Revisionism Failed

David L. Hoggan • 1989 • 320,000 Words

I only recently discovered Hoggan’s opus, and found it exceptionally detailed and comprehensive, though rather dry. I read through the first hundred pages or so, plus a few selections here and there, just a small portion of the 700 pages, but enough to develop a sense of the material.

The short 1989 introduction by the publisher characterizes it as a uniquely comprehensive treatment of the ideological and diplomatic circumstances surrounding the outbreak of the war, and that seems an accurate appraisal, one which may even still hold true today. For example, the first chapter provides a remarkably detailed description of the several conflicting ideological currents of Polish nationalism during the century or so prior to 1939, a very specialized topic that I had never encountered anywhere else nor found of huge interest.

Despite its long suppression, under many circumstances such an exhaustive work based upon many years of archival research might constitute the foundational research for subsequent historians, and indeed various recent revisionist authors have relied upon Hoggan in exactly that manner. But unfortunately there are some serious concerns. Just as we might expect, the overwhelming majority of the discussion of Hoggan found on the Internet is hostile and insulting, and for obvious reasons this might normally be dismissed. However, Gary North, himself a prominent revisionist who personally knew Hoggan, has been equally critical, portraying him as biased, factually unreliable, and even dishonest.

My own sense is that the overwhelming majority of Hoggan’s material is likely correct and accurate, though we might dispute his interpretations. However, given such serious accusations, we should probably treat all his claims with some caution, especially since it would take considerable archival investigation to verify most of his specific research findings. Indeed, since so much of Hoggan’s overall framework of events matches that of Taylor, I think we are far better off generally relying upon the latter.

Fortunately, these same concerns about accuracy can be entirely dismissed in the case of a far more important writer, and one whose voluminous output easily eclipses that of Hoggan or almost any other historian of World War II. As I described David Irving last year:

With many millions of his books in print, including a string of best-sellers translated into numerous languages, it’s quite possible that the eighty-year-old Irving today ranks as the most internationally-successful British historian of the last one hundred years. Although I myself have merely read a couple of his shorter works, I found these absolutely outstanding, with Irving regularly deploying his remarkable command of the primary source documentary evidence to totally demolish my naive History 101 understanding of major historical events. It would hardly surprise me if the huge corpus of his writings eventually constitutes a central pillar upon which future historians seek to comprehend the catastrophically bloody middle years of our hugely destructive twentieth century even after most of our other chroniclers of that era are long forgotten.

When confronted with astonishing claims that completely overturn an established historical narrative, considerable skepticism is warranted, and my own lack of specialized expertise in World War II history left me especially cautious. The documents Irving unearths seemingly portray a Winston Churchill so radically different from that of my naive understanding as to be almost unrecognizable, and this naturally raised the question of whether I could credit the accuracy of Irving’s evidence and his interpretation. All his material is massively footnoted, referencing copious documents in numerous official archives, but how could I possibly muster the time or energy to verify them?

Rather ironically, an extremely unfortunate turn of events seems to have fully resolved that crucial question.

Irving is an individual of uncommonly strong scholarly integrity, and as such he is unable to see things in the record that do not exist, even if it were in his considerable interest to do so, nor to fabricate non-existent evidence. Therefore, his unwillingness to dissemble or pay lip-service to various widely-worshiped cultural totems eventually provoked an outpouring of vilification by a swarm of ideological fanatics drawn from a particular ethnic persuasion. This situation was rather similar to the troubles my old Harvard professor E.O. Wilson had experienced around that same time upon publication of his own masterwork Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, the book that helped launch the field of modern human evolutionary psychobiology.

These zealous ethnic-activists began a coordinated campaign to pressure Irving’s prestigious publishers into dropping his books, while also disrupting his frequent international speaking tours and even lobbying countries to bar him from entry. They also maintained a drumbeat of media vilification, continually blackening his name and his research skills, even going so far as to denounce him as a “Nazi” and a “Hitler-lover,” just as had similarly been done in the case of Prof. Wilson.

During the 1980s and 1990s, these determined efforts, sometimes backed by considerable physical violence, increasingly bore fruit, and Irving’s career was severely impacted. He had once been feted by the world’s leading publishing houses and his books serialized and reviewed in Britain’s most august newspapers; now he gradually became a marginalized figure, almost a pariah, with enormous damage to his sources of income.

In 1993, Deborah Lipstadt, a rather ignorant and fanatic professor of Theology and Holocaust Studies (or perhaps “Holocaust Theology”) ferociously attacked him in her book as being a “Holocaust Denier,” leading Irving’s timorous publisher to suddenly cancel the contract for his major new historical volume. This development eventually sparked a rancorous lawsuit in 1998, which resulted in a celebrated 2000 libel trial held in British Court.

That legal battle was certainly a David-and-Goliath affair, with wealthy Jewish movie producers and corporate executives providing a huge war-chest of $13 million to Lipstadt’s side, allowing her to fund a veritable army of 40 researchers and legal experts, captained by one of Britain’s most successful Jewish divorce lawyers. By contrast, Irving, being an impecunious historian, was forced to defend himself without benefit of legal counsel.

In real life unlike in fable, the Goliaths of this world are almost invariably triumphant, and this case was no exception, with Irving being driven into personal bankruptcy, resulting in the loss of his fine central London home. But seen from the longer perspective of history, I think the victory of his tormenters was a remarkably Pyrrhic one.

Although the target of their unleashed hatred was Irving’s alleged “Holocaust denial,” as near as I can tell, that particular topic was almost entirely absent from all of Irving’s dozens of books, and exactly that very silence was what had provoked their spittle-flecked outrage. Therefore, lacking such