Does anyone use the IMF’s SDR?

by JP Koning, BullionStar:

Last week I poked some fun at the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing rights. I claimed that no on uses them. I wouldn’t be the first to make this accusation. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) itself once described the role that special drawing rights (SDRs) play as “insignificant”.

In response, people tweeted out some interesting uses of SDRs that I wasn’t previously aware of. In this post I’ll do a run-down of the surprising places that SDRs make an appearance.

No one uses the IMF’s SDR as a unit-of-account.

One exception. If you lose your life at sea, the ship owner’s liability is limited to 3.02 million SDRs. So says International Maritime Organization: https://t.co/a4aRSGymip pic.twitter.com/S3uxRdN308

— John Paul Koning (@jp_koning) September 25, 2019

Let’s start from the beginning

First, what is an SDR? The SDR was introduced in 1969 by the IMF as a transferable reserve asset. At the time economists were worried about a shortage of reserve assets, specifically gold and U.S. dollars. The SDR was intended to be a version of paper gold. Rather than holding gold or dollars in their portfolio, central banks could substitute SDRs. The IMF designed SDRs so that they could also be used to make payments to other IMF members.

Ownership of SDRs has always been limited to the IMF’s member nations (currently 189) and a small group of non-members, or “prescribed holders.” These group of prescribed holders includes supra-national central banks such as the European Central Bank, intergovernmental organizations such as the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and development institutions like the African Development Bank. Notably, individuals and corporations can not hold or transact in SDRs.

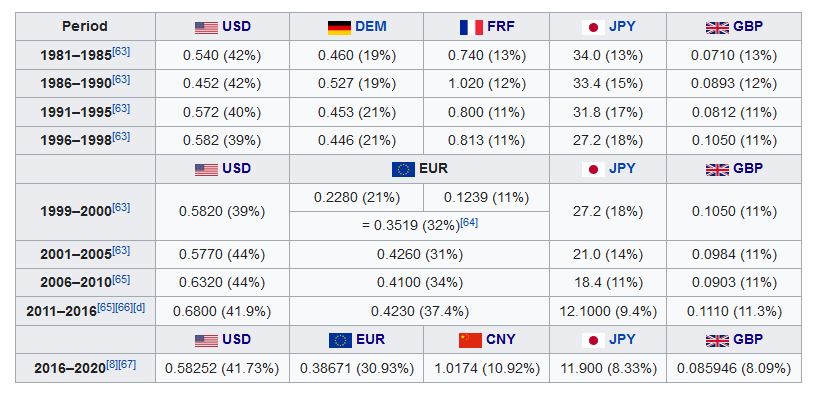

In addition to serving as a specialized payments medium, the SDR acts as a unit of account, or a way of expressing value. Originally defined as 0.888671 grams of gold, in 1976 this definition was changed to a basket of currencies that currently includes the U.S. dollar, euro, Chinese yuan, sterling, and yen.

The chart above shows the history of the basket going back to 1981. The most recent change to the cocktail of currencies making up the SDR is the addition of the Chinese yuan in 2016.

A (mostly) failed experiment

My original tweet implied that the SDR is a failure. And in most cases, this assessment is correct. The SDR never really took off as a transferable reserve asset. One reason for this is that not many of them were issued. Another is that SDRs are just not as useful as U.S. dollars. Since most of the world is prohibited from owning SDRs, a central bank that keeps some in reserve can only mobilize them after converting them into dollars or euros. The result is that SDRs tended to accumulate back at the IMF rather than being traded between members, a phenomenon I once described here.

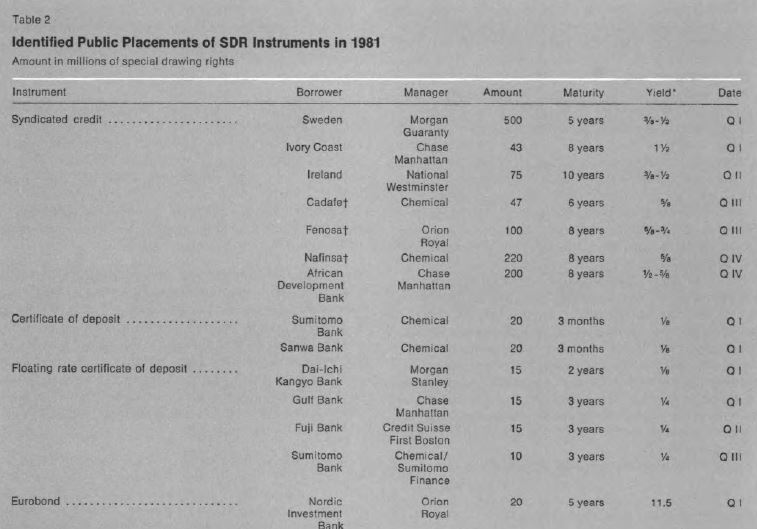

What about usage of the SDR as a unit of account? Early on, the private sector began to experiment with SDRs by using them to denominate financial securities and to offer banking services. For instance, in 1975 Chase Manhattan Bank began to provide SDR-linked bank accounts (see Aschheim & Park, 1976). These weren’t official SDRs. After all, the private sector was not allowed to hold the real thing. Rater, these were a bank-provided version of transferable SDRs .

In a 1981 paper, Sobol documents a number of bonds and other credit instruments that were denominated in SDR:

Since then activity has tailed off. Today, China seems to be the only nation active in the SDR-denominated bond space as it tries to kick-start a nascent Mulan bond market.

If you lose your bag, you get 1,130 SDRs

The SDR doesn’t get much usage as a reserve asset nor as a private unit-of-account. But there is one niche in which it seems to have become popular. The SDR has become a widely used unit-of-account in international treaties and law. Government-owned corporations, international agencies, and other intergovernmental organizations have also adopted the SDR for accounting purposes.

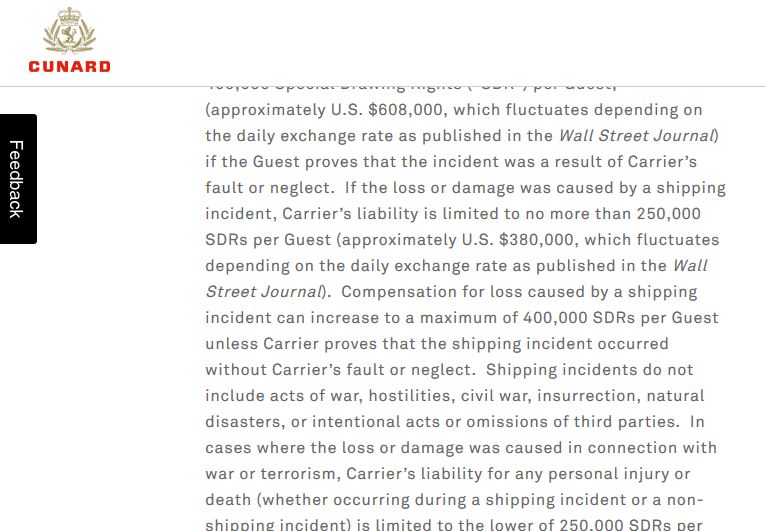

Say that you take a flight or go on a cruise boat and you lose your life or get injured. In either case the standard amount you (or your family) can claim is set in SDR terms. Should you drown, your family is entitled to no more than 250,000 SDRs (US$340,000). In case of an air disaster, the award is 113,100 SDRs (US$150,000).

These amounts are stipulated in two different international conventions, or treaties. The first is the Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules for International Carriage by Air (otherwise known as the Montreal Convention). The other is the Athens Convention relating to the Carriage of Passengers and their Luggage by Sea (link).

Below is the fine print of a Cunard Lines ticket. Cunard offers luxury cruises. The SDR liability limits that it lists come straight out of the Athens Convention.

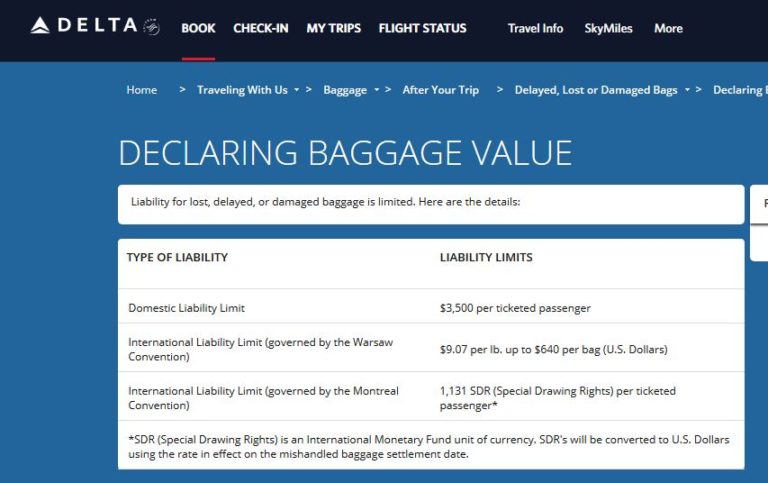

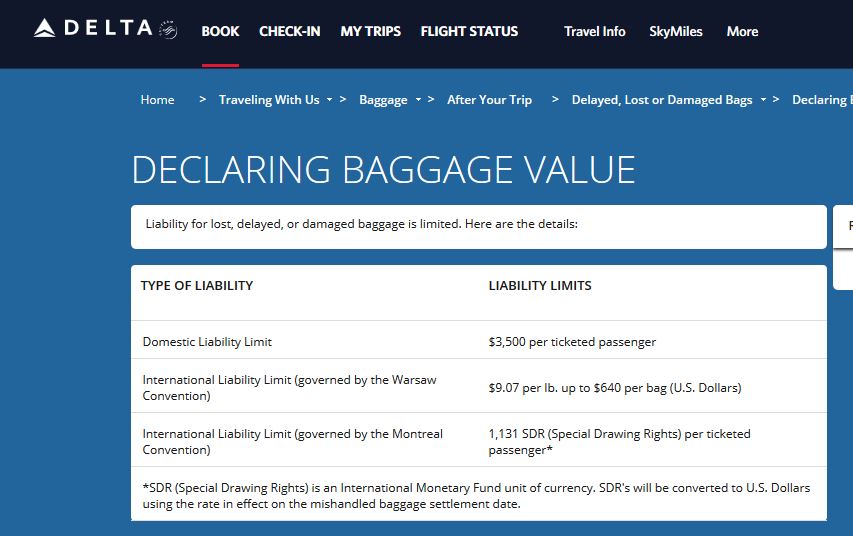

The Montreal Convention also stipulates that airlines are liable for up to 1,131 SDRs (US$1,500) per lost or damaged bag for damaged or lost luggage. This figure can be located in the fine-print of any airline contract. Below I’ve provided a screenshot of a Delta contract:

Along with the Montreal Protocol, several other conventions govern liability limits for luggage and cargo. The Convention on the Contract of International Carriage of Passengers and Luggage by Road (CMR) sets a 8.33 SDR per kilo limit on cargo damaged while being transported by road. Rail liability limits are regulated by the The Convention Concerning International Carriage by Rail (CIM) at 17 SDRs per kilogram. A trio of protocols set the amount of damage that can be rewarded for cargo damaged on sea. These include the Hague-Visby rules, Hamburg rules, and Rotterdam rules (2, 2.5, and 3 SDRs per kilogram respectively).

Loading...