Sam Francis and the Triple Melting Pot: Race vs. Religion, by E. Michael Jones

“The civilization that we as whites created in Europe and America could not have developed apart from the genetic endowments of the creating people.”

— Samuel Francis

American Renaissance Conference, May 1994

“In sum, the diminution and rupture of the human family and the rise of identity politics are not only happening at the same time. They cannot be understood apart from one another.”

— Mary Eberstadt, Primal Screams

It was sheer coincidence, which of course does not exist in the mind of God, that allowed me to take part in this year’s Arbaeen march organized largely by Iraqi Shi’a in Dearborn, Michigan. My opportunity to go on the real Arbaeen pilgrimage from Najaf to Karbala in Iraq to mourn the death of Hussein ibn Ali at the hands of the wicked Khalif Yazid had been thwarted by an unexpected surgery three years ago. Participating in the American replication of that march was more interesting from a sociological point of view because it allowed me to ponder one of the fundamental pillars of ethnic life in America, namely, the Triple Melting Pot. For those who are unaware of its existence, the Triple Melting Pot is “a metaphor that describes a pattern of assimilation in which various nationality groups merge through intermarriage, but with a strong tendency to do so within the three major religious groupings: Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish.” The Triple Melting Pot argues that “as immigrants assimilated into American culture, religious boundaries would replace ethnic boundaries as the main point of differentiation among people of European descent in the United States.”

In spite of the claim in the Pledge of Allegiance that we are “one nation under God,” America is a country of three nations or ethnic groups under God based on three religions, Protestant, Catholic, and Jew. Religion, in other words, is the source of ethnic identity in America. According to Will Herberg, the most famous popularizer of the Triple Melting Pot concept, America demanded that immigrants learn how to speak English “from the very beginning,” but “we did not really expect a man to change his faith,” because “almost from the beginning, the structure of American society presupposed diversity and substantial equality of religious associations.” Religion supplied the identity which was missing after the third generation lost its immigrant grandparents’ language. Unlike the foreign language which separated immigrants from their new American neighbors, “the old ethnic religion” was:

both genuinely American and a familiar principle of group identification. The connection with the family religion had never been completely broken, and to religion, therefore, the men and women of the third generation now began to turn to define their place in American society in a way that would sustain their Americanness and yet confirm the tie that bound them to their forebears, whom they now no longer had any reason to reject, whom indeed, for the sake of a “heritage,” they now wanted to “remember.” Thus “religion became the focal point of ethnic affiliations.… Through its institutions, the church supplied a place where children could learn what they were.…”

Herberg based his understanding of the Triple Melting Pot on an article by Ruby Jo Kennedy which appeared in the January 1944 issue of the American Journal of Sociology under the title “Single or Triple Melting Pot?” That article analyzed marriage patterns among large nationality groups in New Haven, Connecticut and found that “while strict ethnic endogamy is loosening, religious endogamy is persisting.” Catholics, Kennedy discovered:

married Catholics in 95.35% of the cases in 1870, 85.78% in 1900, 82.05% in 1930, and 83.71% in 1940; members of Protestant stocks married Protestants in 99.11% of the cases in 1870, 90.86% in 1900, 78.19% in 1930, and 79.72% in 1940; Jews married Jews in 100% of the cases in 1870, 98.82% in 1900, 97.01% 1930, and 94.32% in 1940.

After reviewing the data, Kennedy concluded that: “The traditional ‘single melting pot’ idea must be abandoned, and a new conception, which we term the ‘triple melting pot’ theory of American assimilation, will take its place, as the true expression of what is happening to the various nationality groups in the United States” and that this division “seems likely to characterize American society in the future.” After three generations in America, when the grandchildren of the first wave of immigration had lost the language of its forebears, the religious community becomes the “over-all medium” in which “remaining ethnic concerns are preserved, redefined and given appropriate expression.” Being a generic American wasn’t enough. Ethnic identity was essential because it answered the basic question: Who am I? Herberg points out that:

When an American asks of a new family in town, “What does he do?”, he means the occupation or profession of the head of the family, which helps define its social-class status. But when today he asks, “What are they?”, he means to what religious community do they belong, and the answer is in such terms as: “They’re Catholic (or Protestant, or Jewish).” A century or even half a century ago, the question, “What are they?”, would have been answered in terms of ethnic-immigrant origin: “They’re Irish (or Germans, or Italians, or Jews).”

This means that those who lack religious affiliation in America lack identity. As Herberg puts it: “Unless one is either a Protestant, or a Catholic, or a Jew, one is a “nothing”; to be a “something,” to have a name, one must identify oneself to oneself, and be identified by others, as belonging to one or another of the three great religious communities in which the American people are divided.”

Will Herberg died on March 26, 1977, long before Muslim immigration became a significant issue in American life, largely thanks to the 1965 Immigration Bill proposed by New York’s Jewish Senator Jacob Javits. The intention of the bill was to dilute European ethnicity, but the Jewish intervention into immigration also denied Muslims a place in the Triple Melting Pot. Herberg is adamant in insisting that “in order to be ‘something’ one must be either a Protestant, a Catholic, or a Jew” in a negative sense which excluded Muslims. Jews had a place at the table, but the church played the main role in “identity politics” in the 1950s, because “the church supplies a place where children come to learn what they are.”

Ten years ago, I attempted to make this point at a memorial service for the paleo-conservative thinker Sam Francis when I claimed that the culture wars weren’t fought along racial lines, but they were fought along ethnic lines. Sam and I were both “white,” whatever that meant, but we belonged to two different ethnic groups because ethnicity in America is based on religion. I then brought up the Triple Melting Pot and claimed that America far from being some unified nation inhabited by generic Americans turns out to be a lot like the former Yugoslavia, a country made up of three ethnic groups based on three religions, each engaged in a form of long-standing covert (and in Yugoslavia, oftentimes overt) warfare against each other. As I attempted to show in my book The Slaughter of Cities, one of the most common forms of warfare in both America and Yugoslavia involves ethnic cleansing.

I bring up the connection between Sam Francis and the Triple Melting Pot now because the posthumous publication of his book Leviathan and its Enemies has sparked renewed interest in his writings. Francis, according to an article by Matthew Rose in First Things:

was a pathologist of American conservatism, a movement he considered terminally ill even during its years of seeming health. As Republicans won five of seven presidential elections and took control of Congress for the first time in four decades, Francis saw a movement being assimilated slowly into the structures of power it professed to reject.

Unfortunately, Francis was unable to stop this inexorable process of assimilation, and so ended up writing “essays in small-circulation journals” like Chronicles, which:

applauded his attacks on globalism and his defenses of those he called, without irony, “real Americans.” But he won almost no access to major conservative outlets, where his views were denounced, with varying degrees of accuracy, as racist, chauvinist, and unpatriotic. Francis spent his last decade as an editor of far-right newsletters, having been fired by the Washington Times in 1995 for defending the morality of slavery.

Rose makes it look as if Sam Francis had no one to blame but himself for his demise as a pundit, but that was not the case. During a conversation I had with Sam shortly before he died, Sam told me that he had lost his post as columnist at the Washington Times because the ADL had issued a fatwa against him, and because William F. Buckley, editor and founder of the conservative journal National Review had gone in person to the editorial board of the Washington Times and demanded that he be fired.

So the story of Sam and slavery is one more example of the sanitized version of conservatism that First Things was created to promote. First Things was a Jewish creation, specifically intended to marginalize the paleoconservatism that Sam represented at magazines like Chronicles, then being edited by Tom Fleming, Sam’s friend from their graduate school days in the Classics department at the University of North Carolina. When we were on speaking terms (more on that later), Tom told me of a conversation with soon-to-be First Things founder Richard John Neuhaus in which Neuhaus threatened to “cut [Fleming] off at the knees.” Neuhaus did this when he founded First Things by hijacking a $250,000 grant from the Bradley Foundation with the help of two Jewish accomplices, Norman Podhoretz and Midge Dector, the then reigning power couple of neoconservatism.

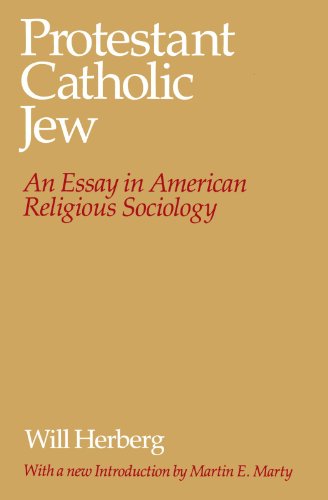

Herberg’s popularization of the Triple Melting Pot theory appeared in his 1954 book Protestant, Catholic, Jew, which rolled off the presses in the same year that the Supreme Court handed down its Brown vs. Board of Education ruling, which inaugurated the current wave of racial consciousness in America. But that was over the horizon of time in 1954. During the years immediately following its publication, Protestant, Catholic, Jew became a best-seller, garnering over 40 reviews in the year following its publication and dominating the discussion of ethnicity for influential figures like Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Within a decade of its publication, however, sociologists were saying that Herberg’s analysis was outdated because it ignored race. Herberg ran afoul of both the universalists, who claimed that there was only a single melting pot and one undifferentiated American group, and the ethnic particularism of the sort defended by Michael Novak in his mid-1970s book The Rise of the Unmeltable Ethnics. “With the rise of race as a serious social concern, and with the defense of group rights and ethnic particularism, Herberg’s star declined.”

Schulz says that Herberg failed to understand that there was “a contested middle ground” missing from Herberg’s discussion of the Triple Melting Pot. Unfortunately, Schulz failed to identify what it was. Schulz failed to see that the missing “contested middle ground” is ethnicity.

Because of his background, Sam found any clear understanding of either religion or ethnicity problematic. Sam Francis was born in 1947 in Chattanooga, Tennessee at a time when the main ethnic indicators were racial. “Down South,” as Dorothy Tillman later famously stated, “you were either black or white. You wasn’t Irish or Polish or all of this.”

Sam came from a time and place that had little to no understanding of ethnicity as it existed in America. He was presumably raised as a Christian, but by the time he received his doctorate from the University of North Carolina in British history, he was a thoroughgoing materialist and skeptic, who drew his intellectual categories from Machiavelli in politics and David Hume in philosophy. Sam “accepted the materialism and secularism which lay at the basis of modern thought, rejecting the primacy of metaphysics and theology.” More importantly in terms of Francis’s intellectual development, he accepted modernity’s description of political life as “an unending contest for power, emphasizing the human appetite for power as our overriding social passion.”

The full version of this article can be found in the December issue of Culture Wars magazine and is available online at https://culturewars.com