The Great American Shale Oil & Gas Bust: Fracking Gushes Bankruptcies, Defaulted Debt, and Worthless Shares

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

Texas at the epicenter. We’re witnessing the destruction of money that loosey-goosey monetary policies encouraged.

Texas at the epicenter. We’re witnessing the destruction of money that loosey-goosey monetary policies encouraged.

Following the sharp re-drop in oil and natural gas prices in late 2018, bankruptcy filings in the US by already weakened exploration and production companies , oilfield services companies, and “midstream” companies (they gather, transport, process, or store oil and natural gas) jumped by 51% in 2019, to 65 filings, according to data compiled by law firm Haynes and Boone. This brought the total of the Great American Shale Oil & Gas Bust since 2015 in these three sectors to 402 bankruptcy filings.

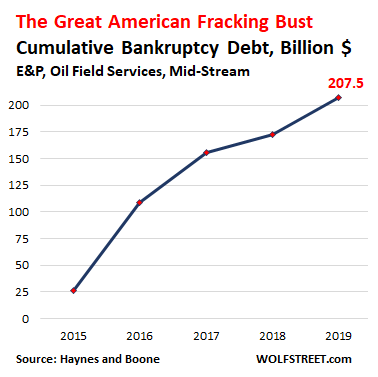

The debt involved in these bankruptcies in 2019 doubled from 2018 to $35 billion. This pushed the total debt listed in these bankruptcy filings since 2015 to $207 billion. The chart below shows the cumulative total debt involved in these bankruptcies since 2015.

But this does not include the much larger losses suffered by shareholders that get mostly wiped out in the years before the bankruptcy as the shares descend into worthlessness, and that then may get finished off in bankruptcy court.

The banks, which generally had the best collateral, took the smallest losses; bondholders took bigger losses, with unsecured bondholders taking the biggest losses. Some of them lost most of their investment; others got high-and-tight haircuts; others held debt that was converted to equity in the restructured companies, some of which soon became worthless again when the company filed for bankruptcy a second time. The old shareholders took the biggest losses.

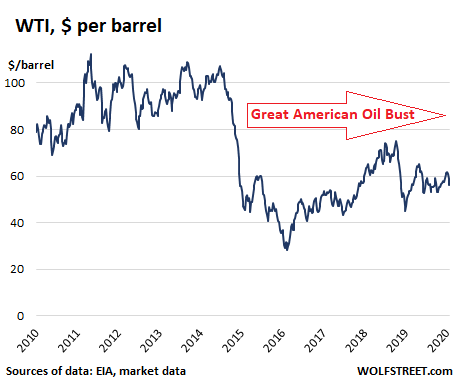

The Great American Fracking Bust started in mid-2014, when the price of WTI dropped from over $100 a barrel to below $30 a barrel by early 2016. Then the price began to recover, going over $70 a barrel in September and October 2018. But then it began to re-plunge. By the end of 2018, WTI had dropped to $47 a barrel.

Two major geopolitical events in the Middle East – the attack on Saudi Aramco’s oil facilities last September and the US assassination of Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani – that would have shaken up oil markets before, only caused brief ripples, quickly squashed by the onslaught of surging US production. At the moment, WTI trades at $56.08 per barrel, which is still below where the shale oil industry can survive long-term:

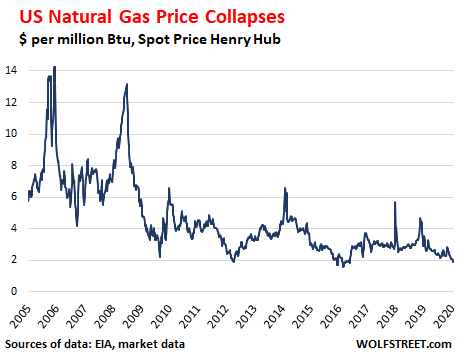

And 2020 is starting out terrible for natural gas producers. The price of natural gas has plunged to $1.90 per million Btu at the moment, a dreadfully low price where no one can make any money. Producers in shale fields that produce mostly gas, such as the Marcellus, are in deeper trouble still, because oil, even at these prices, would be a lot better than just natural gas.

Producing areas with constrained takeaway capacity (it takes a lot longer to build pipelines than to ramp up production) are subject to local prices, which can be lower still. In some areas, such as the Permian in Texas and New Mexico, the most prolific oil field in the US, where natural gas is a byproduct of oil production, limited takeaway capacity has caused local prices to collapse, and flaring to surge.

The chart shows the spot price for delivery at the Henry Hub:

Texas at the epicenter.

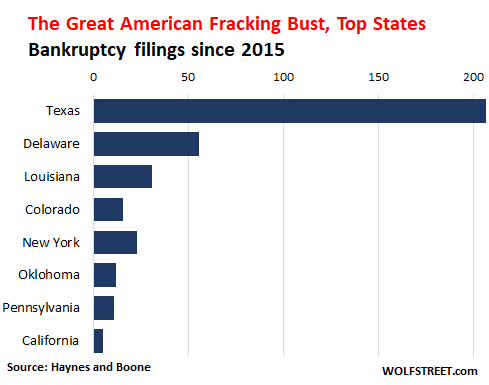

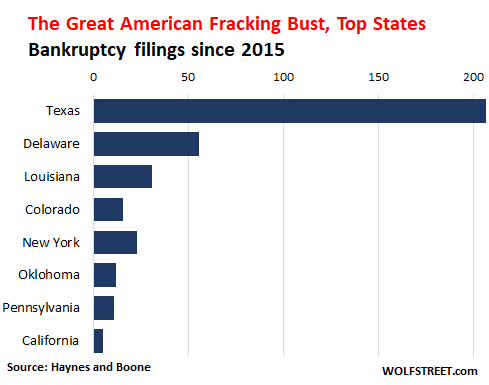

The most affected state, in terms of the number of bankruptcy filings, is Texas, the largest oil producer in the US. Since 2015, the state had 207 oil-and-gas bankruptcy filings, of the 402 total US filings. In 2019, Texas had 30 of the 65 US filings.

Delaware, obviously, is not into oil and gas production, but into coddling corporations, and many companies are incorporated in Delaware, including some oil-and-gas companies in Texas. When they file for bankruptcy, they do so in Delaware. These are the eight states with the most oil-and-gas bankruptcy filings since 2015:

Bankruptcy filings are triggered when the E&P companies no longer get funding from Wall Street or from their banks to continue with their perennially cash-flow negative operations and service their debts. And this is what is happening now. Wall Street and the banks have started to demand that these companies stick to an entirely new mantra in the fracking business: “live within cash flow.”

When E&P companies run short on funding, they cut back on drilling activity which puts the squeeze on oilfield services companies that provide products and services to the oilfield, including drilling and completing wells. And then these OFS companies go bankrupt.

Loading...