American Pravda: Mossad Assassinations, by Ron Unz

The January 2nd American assassination of Gen. Qassem Suleimani of Iran was an event of enormous moment.

The January 2nd American assassination of Gen. Qassem Suleimani of Iran was an event of enormous moment.

Gen. Suleimani had been the highest-ranking military figure in his nation of 80 million, and with a storied career of 30 years, one of the most universally popular and highly-regarded. Most analysts ranked him second in influence only to Ayatollah Khameini, Iran’s elderly Supreme Leader, and there were widespread reports that he was being urged to run for the presidency in the 2021 elections.

The circumstances of his peacetime death were also quite remarkable. His vehicle was incinerated by the missile of an American Reaper drone near Iraq’s Baghdad international airport just after he had arrived there on a regular commercial flight for peace negotiations originally suggested by the American government.

Our major media hardly ignored the gravity of this sudden, unexpected killing of so high-ranking a political and military figure, and gave it enormous attention. A day or so later, the front page of my morning New York Times was almost entirely filled with coverage of the event and its implications, along with several inside pages devoted to the same topic. Later that same week, America’s America’s national newspaper of record allocated more than one-third of all the pages of its front section to the same shocking story.

But even such copious coverage by teams of veteran journalists failed to provide the incident with its proper context and implications. Last year, the Trump Administration had declared the Iranian Revolutionary Guard “a terrorist organization,” drawing widespread criticism and even ridicule from national security experts appalled at the notion of classifying a major branch of Iran’s armed forces as “terrorists.” Gen. Suleimani was a top commander in that body, and this apparently provided the legal figleaf for his assassination in broad daylight while on a diplomatic peace mission.

But consider that Congress has been considering legislation declaring Russia an official state sponsor of terrorism, and Stephen Cohen, the eminent Russia scholar, has argued that no foreign leader since the end of World War II has been so massively demonized by the American media as Russian President Vladimir Putin. For years, numerous agitated pundits have denounced Putin as “the new Hitler,” and some prominent figures have even called for his overthrow or death. So we are now only a step or two removed from undertaking a public campaign to assassinate the leader of a country whose nuclear arsenal could quickly annihilate the bulk of the American population. Cohen has repeatedly warned that the current danger of global nuclear war may exceed that which we faced during the days of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, and can we entirely dismiss such concerns?

Even if we focus solely upon Gen. Solemaini’s killing and entirely disregard its dangerous implications, there seem few modern precedents for the official public assassination of a top-ranking political figure by the forces of another major country. In groping for past examples, the only ones that come to mind occurred almost three generations ago during World War II, when Czech agents assisted by the Allies assassinated Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in 1941 and the US military later shot down the plane of Japanese admiral Isoroku Yamamoto in 1943. But these events occurred in the heat of a brutal global war, and the Allied leadership hardly portrayed them as official government assassinations. During that same conflict, when one of Adolf Hitler’s aides suggested that an attempt be made to assassinate Soviet leaders, the German Fuhrer immediately forbade such practices as obvious violations of the laws of war.

The 1914 terrorist assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, was certainly organized by fanatical elements of Serbian Intelligence, but the Serbian government fiercely denied its own complicity, and no major European power was ever directly implicated in the plot. The aftermath of the killing soon led to the outbreak of World War I, and although many millions died in the trenches over the next few years, it would have been completely unthinkable for one of the major belligerents to consider assassinating the leadership of another.

A century earlier, the Napoleonic Wars had raged across the entire continent of Europe for most of a generation, but I don’t recall reading of any governmental assassination plots during that era, let alone in the quite gentlemanly wars of the preceding 18th century when Frederick the Great and Maria Theresa disputed ownership of the wealthy province of Silesia by military means. I am hardly a specialist in modern European history, but after the 1648 Peace of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years War and regularized the rules of warfare, no assassination as high-profile as that of Gen. Soleimani comes to mind.

The bloody Wars of Religion of previous centuries did see their share of assassination schemes. For example, I think that Philip II of Spain supposedly encouraged various plots to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I of England on grounds that she was a murderous heretic, and their repeated failure helped persuade him to launch the ill-fated Spanish Armada; but being a pious Catholic, he probably would have balked at using the ruse of peace-negotiations to lure Elizabeth to her doom. In any event, that was more than four centuries ago, so America has now placed itself in rather uncharted waters.

Different peoples possess different political traditions, and this may play a major role in influencing the behavior of the countries they establish. Bolivia and Paraguay were created in the early 18th century as shards from the decaying Spanish Empire, and according to Wikipedia they have experienced nearly three dozen successful coups in their history, the bulk of these prior to 1950, while Mexico has had a half-dozen. By contrast, the U.S. and Canada were founded as Anglo-Saxon settler colonies, and neither history records even a failed attempt.

During our Revolutionary War, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and our other Founding Fathers fully recognized that if their effort failed, they would all be hanged by the British as rebels. However, I have never heard that they feared falling to an assassin’s blade, nor that King George III ever considered such an underhanded means of attack. During the first century and more of our nation’s history, nearly all our presidents and other top political leaders traced their ancestry back to the British Isles, and political assassinations were exceptionally rare, with Abraham Lincoln’s death being one of the very few that come to mind.

At the height of the Cold War, our CIA did involve itself in various secret assassination plots against Cuba’s Communist dictator Fidel Castro and other foreign leaders considered hostile to US interests. But when these facts later came out in the 1970s, they evoked such enormous outrage from the public and the media, that three consecutive American presidents—Gerald R. Ford, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan—issued successive Executive Orders absolutely prohibiting assassinations by the CIA or any other agent of the US government.

Although some cynics might claim that these public declarations represented mere window-dressing, a March 2018 book review in the New York Times strongly suggests otherwise. Kenneth M. Pollock spent years as a CIA analyst and National Security Council staffer, then went on to publish a number of influential books on foreign policy and military strategy over the last two decades. He had originally joined the CIA in 1988, and opens his review by declaring:

One of the very first things I was taught when I joined the CIA was that we do not conduct assassinations. It was drilled into new recruits over and over again.

Yet Pollack notes with dismay that over the last quarter-century, these once solid prohibitions have been steadily eaten away, with the process rapidly accelerating after the 9/11 attacks of 2001. The laws on our books may not have changed, but

Today, it seems that all that is left of this policy is a euphemism.

We don’t call them assassinations anymore. Now, they are “targeted killings,” most often performed by drone strike, and they have become America’s go-to weapon in the war on terror.

The Bush Administration had conducted 47 of these assassinations-by-another-name, while his successor Barack Obama, a constitutional scholar and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, had raised his own total to 542. Not without justification, Pollack wonders whether assassination has become “a very effective drug, but [one that] treats only the symptom and so offers no cure.”

Thus over the last couple of decades American policy has followed a very disturbing trajectory in its use of assassination as a tool of foreign policy, first restricting its use to only the most extreme circumstances, next targeting small numbers of high-profile “terrorists” hiding in rough terrain, then escalating those same such killings to the many hundreds. And now under President Trump, the fateful step has been taken of America claiming the right to assassinate any world leader not to our liking whom we unilaterally declare worthy of death.

Pollack had made his career as a Clinton Democrat, and is best known for his 2002 book The Threatening Storm that strongly endorsed President Bush’s proposed invasion of Iraq and was enormously influential in producing bipartisan support for that ill-fated policy. I have no doubt that he is a committed supporter of Israel, and he probably falls into a category that I would loosely describe as “Left Neocon.”

But while reviewing a history of Israel’s own long use of assassination as a mainstay of its national security policy, he seems deeply disturbed that America might be following along that same terrible path. Less than two years later, our sudden assassination of a top Iranian leader demonstrates that his fears may have been greatly understated.

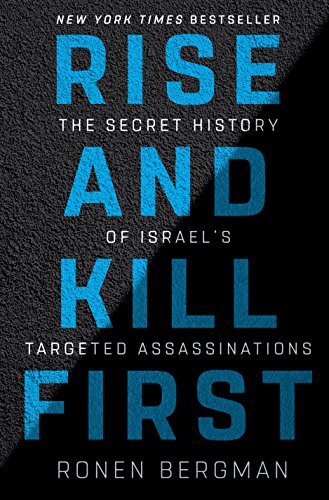

The book being reviewed was Rise and Kill First by New York Times reporter Ronan Bergman, a weighty study of the Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence service, together with its sister agencies. The author devoted six years of research to the project, which was based upon a thousand personal interviews and access to some official documents previously unavailable. As suggested by the title, his primary focus was Israel’s long history of assassinations, and across his 750 pages and thousand-odd source references he recounts the details of an enormous number of such incidents.

That sort of topic is obviously fraught with controversy, but Bergman’s volume carries glowing cover-blurbs from Pulitzer Prize-winning authors on espionage matters, and the official cooperation he received is indicated by similar endorsements from both a former Mossad chief and Ehud Barak, a past Prime Minister of Israel who himself had once led assassination squads. Over the last couple of decades, former CIA officer Robert Baer has become one of our most prominent authors in this same field, and he praises the book as “hands down” the best he has ever read on intelligence, Israel, or the Middle East. The reviews across our elite media were equally laudatory.

Although I had seen some discussions of the book when it appeared, I only got around to reading it a few months ago. And while I was deeply impressed by the thorough and meticulous journalism, I found the pages rather grim and depressing reading, with their endless accounts of Israeli agents killing their real or perceived enemies, with the operations sometimes involving kidnappings and brutal torture, or resulting in considerable loss of life to innocent bystanders. Although the overwhelming majority of the attacks described took place in the various countries of the Middle East or the occupied Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza, others ranged across the world, including Europe. The narrative history began in the 1920s, decades before the actual creation of the Jewish Israel or its Mossad organization, and ranged up to the present day.

The sheer quantity of such foreign assassinations was really quite remarkable, with the knowledgeable reviewer in the New York Times suggesting that the Israeli total over the last half-century or so seemed far greater than that of any other country. I might even go farther, if we excluded domestic killings, I wouldn’t be surprised if the body-count exceeded the combined total for that of all other major countries in the world. I think all the lurid revelations of lethal CIA or KGB Cold War assassination plots that I have seen discussed in newspaper stories might fit comfortably into just a chapter or two of Bergman’s extremely long book.

National militaries have always been nervous about deploying biological weapons, knowing full well that if once released, the deadly microbes might easily spread back across the border and inflict great suffering upon the civilians of the country that deployed them. Similarly, intelligence operatives who have spent their long careers so heavily focused upon planning, organizing, and implementing what amount to judicially-sanctioned murders may develop ways of thinking that become a danger both to each other and to the larger society they serve, and some examples of this possibility leak out here and there in Bergman’s comprehensive narrative.

In the so-called “Askelon Incident” of 1984, a couple of captured Palestinians were beaten to death in public by the notoriously ruthless head of the Shin Bet domestic security agency and his subordinates. Under normal circumstances, this deed would have carried no consequences, but the incident happened to be captured by the camera by a nearby Israeli photo-journalist, who managed to avoid confiscation of his film. His resulting scoop sparked an international media scandal, even reaching the pages of the New York Times, and this forced a governmental investigation aimed at criminal prosecution. To protect themselves, the Shin Bet leadership infiltrated the inquiry and organized an effort to fabricate evidence pinning the murders upon ordinary Israeli soldiers and a leading general, all of whom were completely innocent. A senior Shin Bet officer who expressed misgivings about this plot apparently came close to being murdered by his colleagues until he agreed to falsify his official testimony. Organizations that increasingly operate like mafia crime families may eventually adopt similar cultural norms.

Mossad agents sometimes even contemplated the elimination of top-ranking Israeli leaders whose policies they viewed as sufficiently counter-productive. For decades, Gen. Ariel Sharon had been one of Israel’s greatest military heroes and someone of extreme right-wing sentiments. As Defense Minister in 1982, he orchestrated the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, which soon turned into a major political debacle, seriously damaging Israel’s international standing by inflicting great destruction upon that neighboring country and its capital city of Beirut. As Sharon stubbornly continued his military strategy and the problems grew more severe, a group of disgruntled Mossad officers decided that the best means of cutting Israel’s losses was to assassinate Sharon, though the proposal was never carried out.

An even more striking example occurred a decade later. For many years, Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat had been the leading object of Israeli antipathy, so much so that at one point Israel made plans to shoot down an international civilian jetliner in order to assassinate him. But after the end of the Cold War, pressure from America and Europe led Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin to sign the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords with his Palestinian foe. Although the Israeli leader received worldwide praise and shared a Nobel Peace Prize for his peacemaking efforts, powerful segments of the Israeli public and its political class regarded the act as a betrayal, with some extreme nationalists and religious zealots demanding that he be killed for his treason. A couple of years later, he was indeed shot dead by a lone gunman from those ideological circles, becoming the first Middle Eastern leader in decades to suffer that fate. Although his killer was mentally unbalanced and stubbornly insisted that he acted alone, he had had a long history of intelligence associations, and Bergman delicately notes that the gunman slipped past Rabin’s numerous bodyguards “with astonishing ease” in order to fire his three fatal shots at close range.

Many observers drew parallels between Rabin’s assassination and that of our own president in Dallas three decades earlier, and the latter’s heir and namesake, John F. Kennedy, Jr., developed a strong interest in the tragic event. In March 1997, his glossy political magazine George published an article by the Israeli assassin’s mother, implicating her own country’s security services in the crime, a theory also promoted by the late Israeli-Canadian writer Barry Chamish. These accusations sparked a furious international debate, but after Kennedy himself died in an unusual plane crash a couple of years later and his magazine quickly folded, the controversy soon subsided. The George archives are not online nor easily available, so I cannot easily judge the credibility of the charges.

Having himself narrowly avoided Mossad assassination, Sharon gradually regained his political influence in Israel, and did so without compromising his hard-line views, even boastfully describing himself as a “Judeo-Nazi” to an appalled journalist. A few years after Rabin’s death, he provoked major Palestinian protests, then used the resulting violence to win election as Prime Minister, and once in office, his very harsh methods led to a widespread uprising in Occupied Palestine. But Sharon merely redoubled his repression, and after world attention was diverted by 9/11 attacks and the American invasion of Iraq, he began assassinating numerous top Palestinian political and religious leaders in attacks that sometimes inflicted heavy civilian casualties.

The central object of his anger was Palestine President Yasir Arafat, who suddenly took ill and died, thereby joining his erstwhile negotiating partner Rabin in permanent repose. Arafat’s wife claimed that he had been poisoned and produced some medical evidence to support this charge, while longtime Israeli political figure Uri Avnery published numerous articles substantiating those accusations. Bergman simply reports the categorical Israeli denials while noting that “the timing of Arafat’s death was quite peculiar,” then emphasizes that even if he knew the truth, he couldn’t publish it since his entire book was written under strict Israeli censorship.

This last point seems an extremely important one, and although it only appears just that one time in the text, the disclaimer obviously applies to the entirety of the very long volume and should always be kept in the back of our minds. Bergman’s book runs some 350,000 words and even if every single sentence were written with the most scrupulous honesty, we must recognize the huge difference between “the Truth” and “the Whole Truth.”

Another item also raised my suspicions. Thirty years ago, a disaffected Mossad officer named Victor Ostrovsky left that organization and wrote By Way of Deception, a highly-critical book recounting numerous alleged operations known to him, especially those contrary to American and Western interests. The Israeli government and its pro-Israel advocates launched an unprecedented legal campaign to block publication, but this produced in a major backlash and media uproar, with the heavy publicity landing it as #1 on the New York Times sales list. I finally got around to reading his book about a decade ago and was shocked by many of the remarkable claims, while being reliably informed that CIA personnel had judged his material as probably accurate when they reviewed it.

Although much of Ostrovsky’s information was impossible to independently confirm, for more than a quarter-century his international bestseller and its 1994 sequel The Other Side of Deception have heavily shaped our understanding of Mossad and its activities, so I naturally expected to see a very detailed discussion, whether supportive or critical, in Bergman’s exhaustive parallel work. Instead, there was only a single reference to Ostrovsky buried in a footnote on p. 684. There we are told of Mossad’s utter horror at the numerous deep secrets that Ostrovsky was preparing to reveal, which led its top leadership to formulate a plan to assassinate him. Ostrovsky only survived because Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who had formerly spent decades as the Mossad assassination chief, vetoed the proposal on the grounds that “We don’t kill Jews.” Although this reference is brief and almost hidden, I regard it as providing considerable support for Ostrovsky’s general credibility.

Having thus acquired serious doubts about the completeness of Bergman’s seemingly comprehensive narrative history, I noted a curious fact. I have no specialized expertise in intelligence operations in general nor those of Mossad in particular, so I found it quite remarkable that the overwhelming majority of all the higher-profile incidents recounted by Bergman was already familiar to me simply from the decades I had spent closely reading the New York Times every morning. Is it really plausible that six years of exhaustive research and so many personal interviews would have uncovered so few major operations that had not already been known and reported in the international media? Bergman obviously provides a wealth of detail previously limited to insiders, along with numerous unreported assassinations of relatively minor individuals, but it seems strange that he came up with so few surprising revelations.

Indeed, some major gaps in his coverage are quite apparent to anyone who has even somewhat investigated the topic, and these begin in the early chapters of his volume, which include coverage of the Zionist prehistory in Palestine prior to the establishment of the Jewish state.

Bergman would have severely damaged his credibility if he had failed to include the infamous 1940s Zionist assassinations of Britain’s Lord Moyne or U.N. Peace Negotiator Count Folke Bernadotte. But he unaccountably fails to mention that in 1937 the more right-wing Zionist faction whose political heirs have dominated Israel in recent decades assassinated Chaim Arlosoroff, the highest-ranking Zionist figure in Palestine. Moreover, he omits a number of similar incidents, including some of those targeting top Western leaders. As I wrote last year:

Indeed, the inclination of the more right-wing Zionist factions toward assassination, terrorism, and other forms of essentially criminal behavior was really quite remarkable. For example, in 1943 Shamir had arranged the assassination of his factional rival, a year after the two men had escaped together from imprisonment for a bank robbery in which bystanders had been killed, and he claimed he had acted to avert the planned assassination of David Ben-Gurion, the top Zionist leader and Israel’s future founding-premier. Shamir and his faction certainly continued this sort of behavior into the 1940s, successfully assassinating Lord Moyne, the British Minister for the Middle East, and Count Folke Bernadotte, the UN Peace Negotiator, though they failed in their other attempts to kill American President Harry Truman and British Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin, and their plans to assassinate Winston Churchill apparently never moved past the discussion stage. His group also pioneered the use of terrorist car-bombs and other explosive attacks against innocent civilian targets, all long before any Arabs or Muslims had ever thought of using similar tactics; and Begin’s larger and more “moderate” Zionist faction did much the same.

As far as I know, the early Zionists had a record of political terrorism almost unmatched in world history, and in 1974 Prime Minister Menachem Begin once even boasted to a television interviewer of having been the founding father of terrorism across the world.

In the aftermath of World War II, Zionists were bitterly hostile towards all Germans, and Bergman describes the campaign of kidnappings and murders they soon unleashed, both in parts of Europe and in Palestine, which claimed as many as two hundred lives. A small ethnic German community had lived peacefully in the Holy Land for many generations, but after some of its leading figures were killed, the rest permanently fled the country, and their abandoned property was seized by Zionist organizations, a pattern which would soon be replicated on a vastly larger scale with regard to the Palestinian Arabs.

These facts were new to me, and Bergman seemingly treats this wave of vengeance-killings with considerable sympathy, noting that many of the victims had actively supported the German war effort. But oddly enough, he fails to mention that throughout the 1930s, the main Zionist movement had itself maintained a strong economic partnership with Hitler’s Germany, whose financial support was crucial to the establishment of the Jewish state. Moreover, after the war began a small right-wing Zionist faction led by a future prime minister of Israel attempted to enlist in the Axis military alliance, offering to undertake a campaign of espionage and terrorism against the British military in support of the Nazi war effort. These undeniable historical facts have obviously been a source of immense embarrassment to Zionist partisans, and over the last few decades they have done their utmost to expunge them from public awareness, so as a native-born Israeli now in his mid-40s, Bergman may simply be unaware of this reality.

Bergman’s long book contains thirty-five chapters of which only the first two cover the period prior to the creation of Israel, and if his notable omissions were limited to those, they would merely amount to a blemish on an otherwise reliable historical narrative. But a considerable number of major lacunae seem evident across the decades that follow, though they may be less the fault of the author himself than the tight Israeli censorship he faced or the realities of the American publishing industry. By the year 2018, pro-Israeli influence over America and other Western countries had reached such enormous proportions that Israel would risk little international damage by admitting to numerous illegal assassinations of various prominent figures in the Arab world or the Middle East. But other sorts of past deeds might still be considered far too damaging to yet acknowledge.

In 1991 renowned investigative journalist Seymour Hersh published The Samson Option, describing Israel’s secret nuclear weapons development program of the early 1960s, which was regarded as an absolute national priority by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, There are widespread claims that it was the threatened use of that arsenal that later blackmailed the Nixon Administration into its all-out effort to rescue Israel from the brink of military defeat during the 1973 war, a decision that provoked the Arab Oil Embargo and led to many years of economic hardship for the West.

The Islamic world quickly recognized the strategic imbalance produced by their lack of nuclear deterrent capability, and various efforts were made to redress that balance, which Tel Aviv did its utmost to frustrate. Bergman covers in great detail the widespread campaigns of espionage, sabotage, and assassination by which the Israelis successfully forestalled the Iraqi nuclear program of Saddam Hussein, finally culminating in their long-distance 1981 air raid that destroyed his Osirik reactor complex. The author also covers the destruction of a Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007 and Mossad’s assassination campaign that claimed the lives of several leading Iranian physicists a few years later. But all these events were reported at the time in our major newspapers, so no new ground is being broken. Meanwhile, an important story not widely known is entirely missing.

About seven months ago, my morning New York Times carried a glowing 1,500 word tribute to former U.S. ambassador John Gunther Dean, dead at age 93, giving that eminent diplomat the sort of lengthy obituary usually reserved these days for a rap-star slain in a gun-battle with his drug-dealer. Dean’s father had been a leader of his local Jewish community in Germany, and after the family left for America on the eve of World War II, Dean became a naturalized citizen in 1944. He went on to have a very distinguished diplomatic career, notably serving during the Fall of Cambodia, and under normal circumstances, the piece would have meant no more to me than it did to nearly all its other readers. But I had spent much of the first decade of the 2000s digitizing the complete archives of hundreds of our leading publications, and every now and a particularly intriguing title led me to read the article in question. Such was the case with “Who Killed Zia?” which appeared in 2005.

Throughout the 1980s, Pakistan had been the lynchpin of America’s opposition to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, with its military dictator Zia ul-Haq being one of our most important regional allies. Then in 1988, he and most of his top leadership died in a mysterious plane crash, which also claimed the lives of the U.S. ambassador and an American general.

Although the deaths might have been accidental, Zia’s wide assortment of bitter enemies led most observers to assume foul play, and there was some evidence that a nerve gas agent, possibly released from a crate of mangos, had been used to incapacitate the crew and thereby cause the crash.

At the time, Dean had reached the pinnacle of his career, serving as our ambassador in neighboring India, while the ambassador killed in the crash, Arnold Raphel, had been his closest personal friend, also Jewish. By 2005, Dean was elderly and long-retired, and he finally decided to break his seventeen years of silence and reveal the strange circumstances surrounding the events, saying that he was convinced that the Israeli Mossad had been responsible.

A few years before his death, Zia had boldly declared the production of an “Islamic atomic bomb” as a top Pakistani priority. Although his primary motive was the need to balance India’s small nuclear arsenal, he promised to share such powerful weapons with other Muslim countries, including those in the Middle East. Dean describes the tremendous alarm Israel expressed at this possibility, and how pro-Israel members of Congress began a fierce lobbying campaign to stop Zia’s efforts. According to longtime journalist Eric Margolis, a leading expert on South Asia, Israel repeatedly tried to enlist India in launching a joint all-out attack against Pakistan’s nuclear facilities, but after carefully considering the possibility, the Indian government declined.

This left Israel in a quandary. Zia was a proud and powerful military dictator and his very close ties with the U.S. greatly strengthened his diplomatic leverage. Moreover, Pakistan was 2,000 miles from Israel and possessed a strong military, so any sort of long-distance bombing raid similar to the one used against the Iraqi nuclear program was impossible. That left assassination as the remaining option.

Given Dean’s awareness of the diplomatic atmosphere prior to Zia’s death, he immediately suspected an Israeli hand, and his past personal experiences supported that possibility. Eight years earlier, while posted in Lebanon, the Israelis had sought to enlist his personal support in their local projects, drawing upon his sympathy as a fellow Jew. But when he rejected those overtures and declared that his primary loyalty was to America, an attempt was made to assassinate him, with the munitions used eventually traced back to Israel.

Although Dean was tempted to immediately disclose his strong suspicions regarding the annihilation of the Pakistani government to the international media, he decided instead to pursue proper diplomatic channels, and immediately departed for Washington to share his views with his State Department superiors and other top Administration officials. But upon reaching DC, he was quickly declared mentally incompetent, prevented from returning to his India posting, and soon forced to resign. His four decade long career in government service ended summarily at that point. Meanwhile, the US government refused to assist Pakistan’s efforts to properly investigate the fatal crash and instead tried to convince a skeptical world that Pakistan’s entire top leadership had died due to a simple mechanical failure in their American aircraft.

This remarkable account would surely seem like the plot of an implausible Hollywood movie, but the sources were extremely reputable. The author of the 5,000 word article was Barbara Crossette, the former New York Times bureau chief for South Asia, who had held that post at the time of Zia’s death, while the piece appeared in World Policy Journal, the prestigious quarterly of The New School in New York City. The publisher was academic Stephen Schlesinger, son of famed historian Arthur J. Schlesinger, Jr.

One might naturally expect that such explosive charges from so solid a source might provoke considerable press attention, but Margolis noted that the story was instead totally ignored and boycotted by the entire North American media. Schlesinger had spent a decade at the helm of his periodical, but a couple of issues later he had vanished from the masthead and his employment at the New School came to an end. The text is no longer available on the World Policy Journal website, but it can still be accessed via Archive.org, allowing those so interested to read it and decide for themselves.

Moreover, the complete historical blackout of that incident has continued down to the present day. Dean’s very detailed Times obituary portrayed his long and distinguished career in highly flattering terms, yet failed to devote even a single sentence to the bizarre circumstances that ended it.

At the time I originally read that piece a dozen or so years ago, I had mixed feelings about the likelihood of Dean’s provocative hypothesis. Top national leaders in South Asia do die by assassination rather regularly, but the means employed are almost always quite crude, usually involving one or more gunman firing at close range or perhaps a suicide-bomber. By contrast, the highly sophisticated methods apparently used to eliminate the Pakistani government seemed to suggest a very different sort of state actor. Bergman’s book catalogs the enormous number and variety of Mossad’s assassination technologies.

Given the important nature of Dean’s accusations and the highly reputable venue in which they appeared, Bergman would certainly have been aware of the story, so I wondered what arguments his Mossad sources might muster to rebut or debunk them. Instead, I discovered that the incident appears nowhere in Bergman’s exhaustive volume, perhaps reflecting the author’s reluctance to assist in deceiving his readers.

I also noticed that Bergman made absolutely no mention of the earlier assassination attempt against Dean when he was serving as our ambassador in Lebanon, even though the serial numbers of the anti-tank rockets fired at his armored limousine were traced to a batch sold to Israel. However, sharp-eyed journalist Philip Weiss did notice that the shadowy organization which officially claimed credit for the attack was revealed by Bergman to have been a Israel-created front group they used for numerous car-bombings and other terrorist attacks. This seems to confirm Israel’s responsibility in the assassination plot.

Let us assume that this analysis is correct and that there is a good likelihood that Mossad was indeed behind Zia’s death. The broader implications are considerable.

Pakistan was one of the world’s largest countries in 1988, having a population that was already over 100 million and growing rapidly, while also possessing a powerful military. One of America’s main Cold War projects had been to defeat the Soviets in Afghanistan, and Pakistan had played the central role in that effort, ranking its leadership as one of our most important global allies. The sudden assassination of President Zia and most of his pro-American government, along with our own ambassador, thus represented a huge potential blow to U.S. interests. Yet when one of our top diplomats reported Mossad as the likely culprit, the whistleblower was immediately purged and a major cover-up begun, with no whisper of the story ever reaching our media or our citizenry, even after he repeated the charges years later in a prestigious publication. Bergman’s very comprehensive book contains no hint of the story, and none of the knowledgeable reviewers seem to have noted that lapse.

If an event of such magnitude could be totally ignored by our entire media and omitted from Bergman’s book, many other incidents may also have escaped notice.

A good starting point for such investigation might be Ostrovsky’s works, given the desperate concern of the Mossad leadership at the secrets he revealed in his manuscript and their hopes of shutting his mouth by killing him. So I decided to reread his work after a decade or so and with Bergman’s material now reasonably fresh in my mind.

Ostrovsky’s 1990 book runs just a fraction of the length of Bergman’s volume and is written in a far more casual style while totally lacking any of the latter’s copious source references. Much of the text is simply a personal narrative, and although both he and Bergman had Mossad as their subject, his overwhelming focus was on espionage issues and the techniques of spycraft rather than the details of particular assassinations, although a certain number of those were included. On an entirely impressionistic level, the style of the Mossad operations described seemed quite similar to that presented by Bergman, so much so that if various incidents were switched between the two books, I doubt that anyone could easily tell the difference.

In assessing Ostrovsky’s credibility, a couple of minor items caught my eye. Early on, he states that at the age of 14 he placed second in Israel in target shooting and at 18 was commissioned as the youngest officer in the Israeli military. These seem like significant, factual claims, which if true would help explain the repeated efforts by Mossad to recruit him, while if false would surely have been used by Israel’s partisans to discredit him as a liar. I have seen no indication that his statements were ever disputed.

Mossad assassinations were a relatively minor focus of Ostrovsky’s 1990 book, but it is interesting to compare those handful of examples to the many hundreds of lethal incidents covered by Bergman. Some of the differences in detail and coverage seem to follow a pattern.

For example, Ostrovsky’s opening chapter described the subtle means by which Israel pierced the security of Saddam Hussein’s nuclear weapons project of the late 1970s, successfully sabotaging his equipment, assassinating his scientists, and eventually destroying the completed reactor in a daring 1981 bombing raid. As part of this effort, they lured one of his top physicists to Paris, and after failing to recruit the scientist, killed him instead. Bergman devotes a page or two to that same incident, but fails to mention that the French prostitute who had unwittingly been part of their scheme was also killed the following month after she became alarmed at what had happened and contacted the police. One wonders if numerous other collateral killings of Europeans and Americans accidentally caught up in these deadly events may also have been carefully airbrushed out of Bergman’s Mossad-sourced narrative.

An even more obvious example comes much later in Ostrovsky’s book, when he describes how Mossad became alarmed upon discovering that Arafat was attempting to open peace negotiations with Israel in 1981, and soon assassinated the ranking PLO official assigned to the task. This incident is missing from Bergman’s book, despite its comprehensive catalog of far less significant Mossad victims.

One of the most notorious assassinations on American soil occurred in 1976, when a car-bomb explosion in the heart of Washington D.C. took the lives of exiled former Chilean Foreign Minister Orlando Letalier and his young American assistant. The Chilean secret police were soon found responsible, and a major international scandal erupted, especially since the Chileans had already begun liquidating numerous other perceived opponents across Latin America. Ostrovsky explains how Mossad had trained the Chileans in such assassination techniques as part of a complex arms sale agreement, but Bergman makes no mention of this history.

One of the leading Mossad figures in Bergman’s narrative is Mike Harari, who spent some fifteen years holding senior positions in its assassination division, and according to the index his name appears on more than 50 different pages. The author generally portrays Harari in a gauzy light, while admitting his central role in the infamous Lillehammer Affair, in which his agents killed a totally innocent Moroccan waiter living in a Norwegian town through a case of mistaken identity, a murder that resulted in the conviction and imprisonment of several Mossad agents and severe damage to Israel’s international reputation. By contrast, Ostrovsky portrays Harari as a deeply corrupt individual, who after his retirement became heavily involved in international drug-dealing and served as a top henchman of notorious Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. After Noriega fell, the new American-backed government gleefully announced Harari’s arrest, but the ex-Mossad officer somehow managed to escape back to Israel, while his former boss received a thirty year sentence in American federal prison.

Widespread financial and sexual impropriety within the Mossad hierarchy was a recurrent theme throughout Ostrovsky’s narrative, and his stories seem fairly credible. Israel had been founded on strict socialistic principles and these still held sway during the 1980s, so that government employees were usually paid a mere pittance. For example, Mossad case officers earned between $500 and $1,500 per month depending upon their rank, while controlling vastly larger operational budgets and making decisions potentially worth millions to interested parties, a situation that obviously might lead to serious temptations. Ostrovsky notes that although one of this superiors had spent his whole career working for the government on that sort of meager salary, he had somehow managed to acquire a huge personal estate, complete with its own small forest. My own impression is that although intelligence operatives in America may often launch lucrative private careers after they retire, any agents who became very conspicuously wealthy while still working for the CIA would be facing serious legal risk.

Ostrovsky was also disturbed by the other sorts of impropriety he claims to have encountered. He and his fellow trainees allegedly discovered that their top leadership sometimes staged late-night sexual orgies in the secure areas of the official training facilities, while adultery was rampant within Mossad, especially involving supervising officers and the wives of the agents they had in the field. Moderate former Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was widely disliked in the organization and one Mossad officer regularly bragged that he had personally brought down Rabin’s government in 1976 by publicizing a minor violation of financial regulations. This foreshadows Bergman’s far more serious suggestion of the very suspicious circumstances behind Rabin’s assassination two decades later.

Ostrovsky emphasized the remarkable nature of Mossad as an organization, especially when compared to its late Cold War peers that served the two superpowers. The KGB had 250,000 worldwide employees and the CIA tens of thousands, but Mossad’s entire staff barely numbered 1,200, including secretaries and cleaning personnel. While the KGB deployed an army of 15,000 case officers, Mossad operated with merely 30 to 35.

This astonishing efficiency was made possible by Mossad’s heavy reliance on a huge network of loyal Jewish volunteer “helpers” or sayanim scattered all across the world, who could be called upon at a moment’s notice to assist in an espionage or assassination operation, immediately lend large sums of money, or provide safe houses, offices, or equipment. London alone contained some 7,000 of these individuals, with the worldwide total surely numbering in the tens or even hundreds of thousands. Only full-blooded Jews were considered eligible for this role, and Ostrovsky expresses considerable misgivings about a system that seemed so strongly to confirm every traditional accusation that Jews functioned as a “state within a state,” with many of them being disloyal to the country in which they held their citizenship. Meanwhile, the term sayanim appears nowhere in Bergman’s 27 page index, and there is almost no mention of their use in his text, although Ostrovsky plausibly argues that the system was absolutely central to Mossad’s operational efficiency.

Ostrovsky also starkly portrays the utter contempt that many Mossad officers expressed toward their purported allies in the other Western intelligence services, trying to cheat their supposed partners at every turn and taking as much as they could get while giving as little as possible. He describes what seems a remarkable degree of hatred, almost xenophobia, towards all non-Jews and their leaders, however friendly. For example, Margaret Thatcher was widely regarded as one of the most pro-Jewish and pro-Israel prime ministers in British history, filling her cabinet with members of that tiny 0.5% minority and regularly praising plucky little Israel as a rare Middle Eastern democracy. Yet the Mossad members deeply hated her, usually referred to her as “the bitch,” and were convinced that she was an anti-Semite.

If European Gentiles were regular objects of hatred, peoples from other, less developed parts of the world were often ridiculed in harshly racialist terms, with Israel’s Third World allies sometimes casually described as “monkeylike” and “not long out of the trees.”

Occasionally, such extreme arrogance risked diplomatic disaster as was suggested by an amusing vignette. During the 1980s, there was a bitter civil war in Sri Lanka between the Sinhalese and the Tamils, which also drew in a military contingent from neighboring India. At one point, Mossad was simultaneously training special forces contingents from all three of these three mutually-hostile forces at the same time and in the same facility, so they nearly encountered each other, which would have surely produced a huge diplomatic black eye for Israel.

The author portrays his increasing disillusionment with an organization that he claimed was subject to rampant internal factionalism and dishonesty. He was also increasingly concerned about the extreme right-wing sentiments that seemed to pervade so much of the organization, leading him to wonder if it wasn’t beco