Aspects of Black Anti-Semitism, by Andrew Joyce

“[Jews] infiltrate the Negro neighborhood with stores, and they exploit the Negro more than any other White group — housing, food, clothing — controlling the three basic things Negroes need. They claim to be friendly with Negroes but, when pushed to the wall, they are more injurious, more ruthless, than other Whites.”

Jeremiah X, 1965.

Speaking to the Black historian Horace Mann Bond in 1965, Jeremiah X, then leader of the Atlanta Mosque of the Nation of Islam, argued that “the Jews are the Negro’s worst enemy among whites.” The reason Jews were particularly dangerous, explained Jeremiah, was the fact they “make it a practice to study Negroes; thus they are able to get next to him better than the other whites. He uses the knowledge thus obtained to get close to the Negro, thereby being in a position to stab him with a knife.” This metaphorical knife was both economic and socio-cultural. As well as acting as slumlord, pawnbroker, and merchant, the Jew of the Black world was also a manipulative political actor: “Through their control of the press and of other mass media they are able to make the public feel sorry for Jews. It is so bad today that anybody who speaks out against Jews is immediately clobbered as ‘anti-Semitic.’ They have made the Negroes to believe their sufferings have been greater than those of the Negro in America.”

This is an interesting perspective, to say the least, and for as long as I’ve been interested in anti-Semitism, I’ve been intrigued by the expression of hostility towards Jews among non-Whites. My reasons should be obvious. As I’ve written previously, concerning anti-Semitism in South Korea,

One of the most fundamental positions for White advocates concerned with Jewish influence must be the conviction that antagonism against Jews lies in Jewish behavior rather than solely the cultural pathology or psychological tendencies of non-Jews. A major testing ground for this position is the necessity for anti-Jewish attitudes to be present among geographically, racially, and culturally diverse peoples, and for the reasons behind this antagonism to be fairly uniform.

Black anti-Semitism in the United States is especially interesting in its own right for historical and contemporary cultural, economic, social, and political reasons. From at least the time of the Civil War, Jews, Blacks, and Whites have existed in a fateful racial triad, and Black anti-Semitism has much to tell us about all three groups, the relations between them, and the very nature of anti-Semitism itself. Black anti-Semitism has also maintained a constant, though often low-key, quality, with sporadic violent outbreaks since at least the first decade of the twentieth century, the most recent being the spate of assaults in December 2019. Of equal importance to the reasons behind this hostility is the Jewish response, and how that response molds Jewish understandings of anti-Semitism and determines the character of Jewish apologetics for their own antagonistic behaviors. The Jewish response to Black anti-Semitism will be the subject of a follow-up article, but this essay is primarily intended to provide an overview of some of the main aspects of Black anti-Semitism and its meaning and value to White advocacy. As such, it should be seen as complimenting and extending Kevin MacDonald’s essay “Jews, Blacks, and Race,” included in the 2007 volume Cultural Insurrections.

NBC News caption: Members of a Jewish Orthodox emergency response team work alongside police at the scene of a shooting at a kosher supermarket in Jersey City, N.J., on Dec. 11, 2019.

Features of Black anti-Semitism

In Separation and Its Discontents, Kevin MacDonald identifies the key themes of anti-Semitism as including an understanding that, speaking in general terms, Jews

- represent a separate and clannish foreign group with their own set of interests;

- are highly adept at resource competition and have a tendency towards economic domination;

- tend to engage as cultural actors in order to shape non-Jewish culture to suit Jewish interests;

- form a cohesive political entity that seeks politically dominant roles in non-Jewish societies;

- possess negative personality traits, including the pursuance of a system of dual ethics in which non-Jews can be treated badly and exploited;

- are disloyal to the host nation in all fundamental and meaningful ways

Among the factors mitigating anti-Semitism, one of the most crucial contemporary elements has been the Jewish promotion of multi-ethnic, pluralist societies. As MacDonald explains, “A multicultural society in which Jew are simply one of many tolerated groups is likely to meet Jewish interests, because there is a diffusion of power among a variety of groups and it becomes impossible to develop homogeneous gentile in-groups arrayed against Jews as a highly conspicuous group.” Of particular interest, then, is the extent to which the key themes of anti-Semitism manifest among Blacks, how they manifest, and how the Black position of being a celebrated component feature of pluralism (rather than, as in the case of Whites, being the majority population subjected to pluralism) impacts the mitigation of anti-Semitism.

Common sense would suggest that each ethnic group will inflect the themes of anti-Semitism according the context and precise nature of their own interaction with Jews. In South Korea, organised anti-Jewish hostility was built around the understanding that Jewish financiers, mainly American, with a history of highly exploitative behaviors, were attempting to gain strongholds in South Korean companies like Samsung. As such, the primary theme of anti-Semitism in South Korea has been the understanding that Jews are dangerously adept at resource competition, are financially ruthless and exploitative, are highly ethnocentric, and are powerful in the media and in politics at the highest levels. During the early stages of an attempted expansion of influence by the almost entirely Jewish vulture fund “Elliot Associates,” Media Pen columnist Kim Ji-ho claimed “Jewish money has long been known to be ruthless and merciless.” This was soon followed by the former South Korean ambassador to Morocco, Park Jae-seon, expressing his concern about the influence of Jews in finance when he said, “The scary thing about Jews is they are grabbing the currency markets and financial investment companies. Their network is tight-knit beyond one’s imagination.” A day later, cable news channel YTN aired similar comments by local journalist Park Seong-ho, airing the opinion that “it is a fact that Jews use financial networks and have influence wherever they are born.”

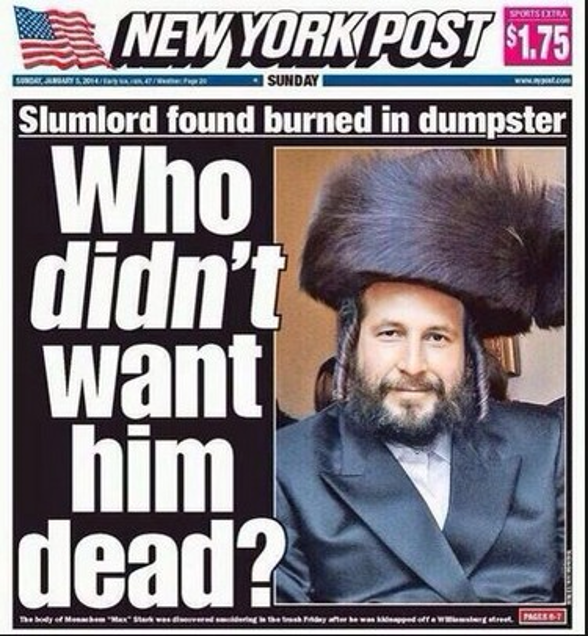

Among Blacks, the same themes have been inflected in less elevated terms, arising first from more modest economic conflicts and, as such, having something more in common with the complaints of the early modern European peasantries. Horace Mann Bond, in his own 1965 reflections on “Negro Attitudes Toward Jews,” comments on the fact Jews historically appeared in the African-American environment overwhelmingly as pawnbrokers, as monopolists of the liquor trade (“The Jews have a stranglehold on the liquor stores in this town”), as the primary sellers on credit of clothing and other essential items, and, perhaps most crucial of all, as the slumlord and property dealer (“Some Jews have bought up that urban re-development land and are putting up shoddy apartments they call “Nigger housing” on it”). In 2016, local news website Patch published a list of the 100 worst slumlords in Harlem, with the top ten including seven Jews (Mark Silber, Adam Stryker, Joel Goldstein, Marc Chemtob, Moshe Deutsch, Solomon Gottlieb, and Jason Green), a representation that has remained roughly constant every year, with Jews persistently claiming top ranking for building violations, rodent infestations, lack of maintenance, exploitative rent, mold, and other forms of building decay injurious to health. Indeed, this situation has at times resulted in considerable embarrassment to Jews.

Indeed, it is the sheer dominance and proximity of the Jews as primary exploiters of Blacks that has often caused a quite radical break in the Black imagination between perceiving wholesale “White oppression,” and the more nuanced understanding that Jews are a distinctive class unto themselves. Moreover, the reality of day-to-day interethnic exploitation leaves little room for abstract apologetic theories of anti-Semitism, since the problem is never that Jews arouse hostility merely on account of their religion or identity, but rather that Jews arouse hostility because of their behavior within certain ecological contexts. As Bond explains,

It is my considered view that Negro attitudes and actions towards Jews that are frequently interpreted as “antisemitic” actually lack the sinister thought-content they are sometimes advertised as holding. The occasional riots against small businessmen and landlords in Harlem — persons who may happen to be Jews — do not, in my opinion, actually possess the “classic” emotional load of aggression against a Jewish “race” or “religion,” that has been considered the essence of antisemitism.

I think Bond, in this instance, waters down the specificity of anti-Jewish hostility that eventually develops, because it’s more or less inevitable in the context of social identity theory that if someone is negatively confronted on enough occasions with “persons who may happen to be Jews” then they will eventually be forced to make an evaluation of Jews as a group. Bond, however, is of course accurate in pointing out that it’s perfectly possible for anti-Jewish actions to occur without the “sinister thought-content” often theorized and expounded upon in Jewish apologetics. Reading between the lines, Bond clearly interprets small-scale violence against these particular Jews as ad hoc reactions to local financial exploitation, an interpretive framework that by contrast has only been employed at the smallest of levels, and with the most minimum impact, when discussing anti-Jewish riots in the European past. Of further value is Bond’s doubting of the putative essence of anti-Semitism, “the classic emotional load of aggression” on the basis of race or religion, which again has only served to distance understandings of anti-Semitism from the realities of antagonistic Jewish group behaviors.

A lot of what has been discussed above is clearly resource-oriented, and economic competition between Blacks and Jews, devastatingly one-sided to be sure, goes right back to the arrival of the African in the Americas. Writing in a 1977 edition of Negro History Bulletin, Oscar R. Williams comments,

The presence of the southern Jews complimented the system of slavery; their mercantilist interest made slavery a more effective labor system. While most Jews were not to be found on plantations, their activities made the plantation a self-sufficient unit. What was not produced on the plantation was delivered by Jewish merchants. The southern Jew has as much, if not more, to gain from the system of maintaining slavery as any other white segment within the South. During the Civil War Jews defended the system which insured them acceptance and success in the South. Neither the Civil War nor Reconstruction changed the southern Jews’ perception of Blacks as an animal to be used and exploited.

While some initial divergence of opinion on race could be found between northern and southern Jews, the advent of the New South, and then the mass migration of Jews to the United States from Eastern Europe in 1880s, provoked a coalescence of Jewish behaviors in relation to Blacks. Williams continues,

Often in the New South, success of Jewish merchants depended on winning Black trade. Jewish merchants appeared more courteous and obviously spent more time with Black customers than fellow white merchants. Blacks were often victims of sales pressure when Jews refused to accept no-sale for an answer. No became the signal for the ritual to begin. Merchants would insist that the potential buyer try-on the item. After this came what Blacks call “Jewing Down,” in which naive Blacks were led to believe that Jewish merchant had allowed himself to be beaten on the price.

The post-Civil War movement of Blacks to the northern cities coincided with the mass migration of East European Jews into the same urban centers. Boasting centuries of experience in the economic exploitation of the lowest classes, Jews quickly set about the establishment of pawn shops, credit sales, and other methods of lending small-to-medium amounts of cash at interest.

Such was the scale of Jewish exploitation of urban Blacks in some areas that W.E.B. Du Bois was moved in 1903 to declare “The Jew is heir to the slavebaron.” And yet, growing alongside this exploitation was something hinted at by Williams. The Jews did in fact appear more courteous than whites, even if their behavior didn’t quite match the outward courtesy. And Jews did obviously spend more time with Black customers than with white merchants. The Black could be “Jewed Down” into believing he’d won himself a bargain, and he could also be “Jewed Down” into the belief that he had a friend and a helper in the form of the Jew, even if this illusion could last only for a short period, and all while the interest clock kept on ticking. Writing in Commentary in 1945, Kenneth B. Clark recounted how Blacks in Baltimore were pointing out that,

Jewish merchants own and control the major downtown department stores. … Some Negro domestics assert that Jewish housewives who employ them are unreasonable and brazenly exploitative. A Negro actor states in bitter terms that he is being flagrantly underpaid by a Jewish producer. A Negro entertainer is antagonistic to his Jewish agent who he is convinced is exploiting him. … Antagonism toward the “Jewish landlord” is so common as to have become almost an integral aspect of the folk culture of the northern urban Negro.

It is indeed a curious feature of American history that the growth of the Black-Jewish civil rights alliance should have coincided with the intensification of Jewish exploitation of Blacks. During the 1920s, the same decade that the mostly Jewish-run NAACP began a serious escalation in agitation for “civil rights,” Jews were invading Black areas in northern cities, using their growing political influence to engage in the exploitation of Blacks and the suppression of their local businesses. In Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition (2012), Marni Davis comments on the Harlem newspaper The Age which complained throughout the early 1920s about Jews who

had bought the police, fouled Harlem with their liquor, and were now poisoning the locals (sometimes literally) and siphoning away the neighbourhood’s hard-earned capital. … The Age noted that many of the stores in question had the name “Hyman” attached to them. They all turned out to be owned by Hyman Kassel [other liquor traders in Harlem included Izzy Einstein, Connie Immerman, and Dutch Schultz], a well-known bootlegger and numbers runner. … “Hebrew Operators Control Lenox Avenue Places,” blared one headline. … The accusations levelled by the Age resembled nativist claims that Jews were economic parasites and moral defilers.

Davis comments that Jews “regarded the anti-alcohol movement as politically wrong-headed — even repulsive — and certainly as inimical to the civil liberties guaranteed by the Constitution,” but such explanations for Jewish opposition to the temperance movement (conservative, Christian, family-oriented) are glaring in their avoidance of the fact Jews possessed centuries of experience in exploiting the sale of liquor to the lowest classes in Eastern Europe in order to obtain and maintain political, social, and economic advancement and control (see Glenn Dynner’s 2014 Princeton-published Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, and Life in the Kingdom of Poland). In other words, the argument that Jews pursued the often harmful sale of liquor purely out of abstract concern for “rights” and freedoms is a rather convenient way of side-stepping obvious, and often criminal, self-interest.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Jewish dominance of the trade in furniture, household items, and other essentials in the Black sections of northern cities led to the development of the idea among Blacks in several cities that Jews “only posed as friends.” These decades witnessed “rent strikes, business boycotts, and other forms of economic pressure,” as well as riots that were “tinged with anti-Semitic feeling,” all of which very closely resembled actions in Eastern Europe around 50 years earlier that had been characterized in contemporary propaganda as irrational and barbaric pogroms. In fact, the causes of both sets of actions are almost entirely identical, with Steven Gold remarking in his fascinating 2010 The Store in the Hood: A Century of Ethnic Business and Conflict that between the 1930s and 1960s Jews “owned many of the largest businesses in ghettos, including department stores, hardware stores, and furniture stores.” Even as Jews moved into the suburbs, unlike other ethnic groups they retained as much economic influence in Black areas as possible, resulting in their becoming “out-group entrepreneurs and absentee landlords.” John Bracey comments,

No other group paid [the Black] the slightest attention: not the Germans, nor the Irish, nor the Poles, nor the Italians, not the Hungarians, nor the Slovaks; only the Jew established a line of communication, albeit a line of communication in trade and credit merchandising. True, the Jew had an advantage. To him the American Negro was no different from the Gentile peasants among whom he lived and with whom he dealt in the towns and villages of Russia, Galicia, Hungary, and Poland.

Everywhere in these areas, remarks Gold, Jews and Blacks existed within a framework of “power and control,” and “The context within which African American women were hired and then supervised in Jewish homes was especially humiliating. At least in New York, this practice came to be known as the “Bronx Slave Market.” After public complaints, the La Guardia administration (1934-1945) created employment offices to provide black domestic workers with an additional measure of security and dignity.”

The period 1945–1960s is often presented in mainstream historiography and social science as involving a Black-Jewish alliance in the pursuit of civil rights for African-Americans. Kevin MacDonald’s theory that this alliance was essentially an almost-entirely Jewish-operated venture in pursuit of Jewish goals and interests (the breaking up, via legislation and cultural change, of notions of America as a White country) has been maligned as itself anti-Semitic, despite the fact such interpretations are present even among Jewish scholars in the academic mainstream. Seymour Weisman, for example, writing in a 1980 edition of the Routledge journal Patterns of Prejudice, comments that “there was an obvious Jewish self-interest to promote legislation and initiate judicial actions” that would broaden the ethnic nature of the United States.

The issue of Jewish self-interest is important because of the obvious implication of rhetorical insincerity. Much like apologetic narratives arguing that Jews traded in liquor, often via monopoly, because they believed in individual rights and freedoms, there are certainly grounds for doubting Jewish claims that they engage in “social justice” work out of sincere belief in the equality of Man. A particularly interesting case in this regard is related by Jeffrey Gurock in his The Jews of Harlem: The Rise, Decline, and Revival of a Jewish Community, where he recounts the great disillusionment of Blacks in the Bronx in the late 1950s on discovering that despite copious public Jewish rhetoric on racial equality, when a predominantly Jewish school in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood (and with a Jewish principal) “accepted five classes of Negroes” from a nearby school, they “isolated them on a separate floor.”

Seymour Weisman claimed in 1981 that it was something of a great mystery that “the breakdown of Black-Jewish relations” should have occurred “at that precise moment in history when the civil rights legislative battle had been won.” In truth, the breakdown only takes on a mysterious aspect if one firstly believes the Black-Jewish alliance to have been sincere in the first place, and, secondly, that if one believes that Jews were sincere in the putative concern for the welfare and well-being of Blacks as a matter of “social justice.” Historical data would instead suggest that Jews were prominent exploiters of Blacks who rather expertly and skillfully created an image of themselves as friends and allies of Blacks. It goes without saying that once Jewish goals in pursuing such a masquerade had been accomplished, the Jewish effort in sustaining the positive but illusory aspects of such a relationship would dramatically decline. In the absence of rhetorical smoke and mirrors, all that remained was the constant of mundane economic, social, and political exploitation in the Black heartlands. This is what has simmered since the 1960s, and this is what bubbled to the surface once again in November 2019.

A fascinating feature of coverage of the Winter 2019/2020 attacks on Jews by Blacks in New York has been the total absence of media enquiry into why the assaults took place. Like so much historiography on European anti-Semitism, there is simply no room for the question Why? As in Kiev, or Odessa, or the Rhine Valley, or Lincoln, or Aragon, or Galicia, the assaults on Jews in Brooklyn apparently emerged from the ether, motivated by some miasmic combination of insanity and demonic aggression. NBC New York reported bluntly on a “spree of hate,” but had nothing in the way of analysis of context other than a condemnation of “possible hate-based attacks” — one of the most remarkably opaque pieces of analytical nomenclature I’ve ever come across. Former New York State Assemblyman Dov Hikind has said “The attacks against Jews are out of control, and we must have a concrete strategy to address the rise of these attacks,” but how he can develop a strategy to address something that apparently does not yet have an explanation is another question left unanswered.

What is clear is that Black anti-Semitism presents Jews with an objective problem in terms of their (publicly-expressed) self-concept as a people and the received wisdom regarding the nature of anti-Semitism (now given quasi-legal standing in many countries via the IHRA definition). The multiple ways in which Jews have sought to deal with this challenge will be addressed in a forthcoming follow-up essay, but it should suffice here to close with the remarks of Steven Gold on the Jewish response to growing Black anti-Semitism in 1940s Harlem:

Being well organized, Jewish communal associations took note when Jewish merchants were accused of inappropriate behavior. When African-American journalists or activists complained about the exploitative behavior of ghetto merchants, Jewish spokesmen often resisted accepting responsibility and instead labeled accusers as anti-Semites for referring to the merchants’ religion. Contending that Jewish merchants treated Blacks no worse than other Whites did, they objected to being singled out.

An age-old pattern had thus been employed with a 20th century twist. Denials of responsibility and accusations of blind and unfair bigotry had been honed to perfection for centuries in Europe, but now came the masterful flourish of the pluralist culture — to dissolve into “Whiteness” at will and direct Black anger at that mask instead. After all, isn’t the Jew the best friend a Black could ask for?

Notes

H.M. Bond “Negro Attitudes Towards Jews,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, Papers and Proceedings of a Conference on Negro-Jewish Relations in the United States (Jan., 1965), 3-9.

K. MacDonald, Separation and Its Discontents: Toward and Evolutionary Theory of anti-Semitism (1st Books, 2004), 87.

Bond “Negro Attitudes Towards Jews,” 5.

Ibid,. 7.

O. Williams (1977). “Historical Impressions of Black-Jewish Relations Prior to World War II”. Negro History Bulletin, 40(4), 728-731.

M. Adams (ed) Strangers & Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks & Jews in the United States (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 18.

K. B. Clark, “Candor about Jewish-Negro Relations,” Commentary, Vol. 1, Dec. 1 1945, 8.

M. Davis, Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition (New York: NYU Press, 2012), 163.

C. Rottenberg, Black Harlem and the Jewish Lower East Side: Narratives Out of Time (New York: State University of New York Press, 2013), 128.

S. Gold, The Store in the Hood: A Century of Ethnic Business and Conflict (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 73.

Ibid., 74.

J. Bracey (ed), Strangers & Neighbors: Relations Between Blacks & Jews in the United States (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 571.

Ibid.

S. S. Weisman (1980) “Black‐Jewish relations in the USA—I: One year after the Andrew young affair,” Patterns of Prejudice, 14:4, 18-28.

J. Gurock, The Jews of Harlem: The Rise, Decline, and Revival of a Jewish Community (New York: NYU Press, 2016), 213.

S. S. Weisman (1981) “Black‐Jewish relations in the USA—II,” Patterns of Prejudice, 15:1, 45-52.

Gold, 75.