Jews and Vulture Capitalism: A Reprise, by Edmund Connelly

I recently wrote a long movie review (sort of) that focused on Wall Street stories that airbrush Jews out of the picture and instead create the impression that plain old goy males are responsible for all kinds of financial nastiness when dealing with sums over, say, a hundred million dollars (and MUCH more). The review came as Part 1 & Part 2. In the review, I emphasized the plots of popular Hollywood movies and deliberately downplayed detailed accounts of Jewish financial manipulation in institutions in Lower Manhattan, reasoning that many of today’s readers would relate more to celluloid imagery than drier non-fiction.

Today I’ll do that drier writing and perform yeoman’s work in describing instances of Jewish financial chicanery far more thoroughly, relying primarily on TOO writers such as Andrew Joyce and myself, though I will bring in a few outsiders to burnish our tale by using their more mainstream credentials.

I’ll begin with a few exciting quotes about our topic before descending into a routine rendition of Jewish perfidy when it comes to large financial scandals. Recall the title of Joyce’s dangerous title last December: “Vulture Capitalism is Jewish Capitalism.” In that essay, Joyce employed provocative phrases, accusing Jewish firms such as Paul Singer’s Elliot Associates of being one of the “cabals of exploitative financiers” possessing a “scavenging and parasitic nature” vis-a-vis gentile host nations. “Jewish enterprise — exploitative, inorganic” — results in “all forms of financial exploitation and white collar crime. The Talmud, whether actively studied or culturally absorbed, is their code of ethics and their curriculum in regards to fraud, fraudulent bankruptcy, embezzlement, usury, and financial exploitation. Vulture capitalism is Jewish capitalism.” I daresay we are here teetering on the brink of introducing age-old canards regarding Jews and money. But are they true?

Before attempting to answer that question either way, it is unavoidable that I once again trot out Rolling Stone reporter Matt Taibbi’s timeless quip in The Great American Bubble Machine as he described the 2008 market meltdown:

The first thing you need to know about Goldman Sachs is that it’s everywhere. The world’s most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.

And with that, we get down to the dirty business of recounting seminal instances of, well, dirty business. Or maybe it’s an historical account of the transfer of wealth from various groups to Jews. Or a biological account of energy moving to one specific colony of living organisms from elsewhere. The phenomenon can be approached in many ways.

To give this essay a suitably serious tone, we begin with the Bible, where the twin themes of Jewish resource acquisition and deceit will be familiar. In A People That Shall Dwell Alone: Judaism as a Group Evolutionary Strategy, Kevin MacDonald describes the process:

The biblical stories of sojourning by the patriarchs among foreigners are very prominently featured in Genesis. Typically there is an emphasis on deception and exploitation of the host population, after which the Jews leave a despoiled host population, having increased their own wealth and reproductive success. Indeed, immediately after the creation story and the genealogy of Abraham, Genesis presents an account of Abraham’s sojourn in Egypt. Abraham goes to Egypt to escape a famine with his barren wife Sarah, and they agree to deceive the pharaoh into thinking that Sarah is his sister, so that the pharaoh takes her as a concubine. As a result of this transaction, Abraham receives great wealth . . . .

Far from being a unique story, it portrays a pattern, with MacDonald concluding, “Like the others, the Egyptian sojourn begins with deception and ends with the Israelites obtaining great treasure and increasing their numbers.”

The most famous Biblical story of deceit is the story of Exodus, where Joseph helps his relatives enter by telling them to deny being shepherds because the Egyptians dislike shepherds. The Israelites reside in Egypt and are successful: “And Israel dwelt in the land of Egypt . . . and they got them possessions therein, and were fruitful, and multiplied exceedingly” (Gen. 47:27).

From biblical times, we jump ahead to the modern era, for Jews seemed to be in a kind of hibernation until their emancipation in Europe. With that emancipation came a resumption of the biblical trend toward obtaining great treasure and increasing their numbers. How they did this often contravened prevailing Christian norms, however, as attested to by two prominent gentile writers outside the realm of TOO or related enterprises.

These eminent writers and thinkers are Paul Johnson, a conservative British writer, and Albert Lindemann, a Harvard Ph.D. and retired historian who has written dispassionately on Jews for many years. Johnson caught my attention years ago when I somehow came across his book Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Eighties. I was a young man then, grappling with a humanities education that left me feeling major parts of life’s stories had been left out. Given the prevailing reign of liberal thought (which was, of course, only to get far worse) I found Johnson’s contrarian conservative views refreshing, but it was his emphasis on Jewish “rationalization” of the modern world, especially in economic matters, that truly caught my attention. I can still recall the ongoing frustration I had while reading his book, principally because he would not call Jews out for bad behavior.

Actually, that’s not entirely true. What Johnson did was start by saying how much Jews had contributed to the modern world, then switch to a long, detailed list of behaviors that violated Western laws and customs. I remember wondering how he got away with that. After filling pages with shocking exposés of such conduct, he’d then close by saying how grateful we should be to Jews for “rationalizing” previously outmoded methods and beliefs. A few years later he wrote A History of the Jews, which is pretty much an expanded version of the Jewish parts of Modern Times. A History is a great reference book to have, though.

Johnson set the stage by documenting the rise of the Jews throughout Europe in the modern period:

Jews dominated the Amsterdam stock exchange, where they held large quantities of stock from both the West and East India Companies, and were the first to run a large-scale trade in securities. In London they set the same pattern a generation later in the 1690s. . . . In due course, Jews helped to create the New York stock exchange in 1792. . . . Expelled Jews went to the Americas as the earliest traders. They set up factories. In St Thomas, for instance, they became the first large-scale plantation-owners [and slave owners]. . . . Jews and marranos were particularly active in settling Brazil . . . they owned most of the sugar plantations [and their slaves]. They controlled the trade in precious and semi-precious stones. Jews expelled from Brazil in 1654 helped to create the sugar industry in Barbados and Jamaica.

Next, he shared how some gentiles reacted: In 1781 Prussian official Christian Wilhelm von Dohm published a tract claiming, in Johnson’s paraphrase, “The Jews had ‘an exaggerated tendency [to seek] gain in every way, a love of usury.’ These ‘defects’ were aggravated ‘by their self-imposed segregation. . . .’ From these followed ‘the breaking of the laws of the state restricting trade, the import and export of prohibited wares, the forgery of money and precious metals.’” In short, von Dohm described traditional Jewish communities as far more resembling a mafia-like group engaged in organized crime than what we think of as a religious community.

Continuing, Johnson wrote,

Throughout the twentieth century, American Jews continued to take the fullest advantage of the opportunities America opened to them, to attend universities, to become doctors, lawyers, teachers, professional men and women of all kinds, politicians and public servants, as well as to thrive in finance and business as they always had. They were particularly strong in the private enterprise sector, in press, publishing, broadcasting and entertainment, and in intellectual life generally. There were certain fields, such as the writing of fiction, where they were dominant. But they were numerous and successful everywhere.

This success, however, did not always come honorably, or at least that is what legions of gentiles have long claimed. Johnson described how Jewish involvement in financial scandals certainly became a prominent theme of modern anti-Semitism. As he wrote, “The Union Générale scandal in 1882, the Comptoire d’Escompte scandal in 1889 — both involving Jews — were merely curtain-raisers” to a far more massive and complex crime, the Panama Canal scandal, ‘an immense labyrinth of financial manipulation and fraud, with [Jewish] Baron Jacques de Reinach right at the middle of it.’” (Reinach committed suicide because of the scandal.) Wikipedia tells us that

Close to half a billion francs were lost and members of the French government had taken bribes to keep quiet about the Panama Canal Company’s financial troubles in what is regarded as the largest monetary corruption scandal of the 19th century. . . . Some 800,000 French people, including 15,000 single women, had lost their investments in the stocks, and founder shares of the Panama Canal Company, to the considerable sum of approximately 1.8 billion gold Francs. From the nine stock issues, the Panama Canal Company received 1.2 billion gold Francs, 960 million of which were invested in Panama, a large amount having been pocketed by financiers and politicians.

For once, Wiki includes the Jewish angle, writing that “The scandal showed, in Arendt’s view, that the middlemen between the business sector and the state were almost exclusively Jews, thus helping to pave the road for the Dreyfus Affair.”

Albert Lindemann chronicled similar episodes, particularly in his highly respected Esau’s Tear: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews. In the book he noted that during the 19th century in Eastern Europe there were also persistent complaints about Jewish perjury to help other Jews commit fraud and other crimes. For example, in Russia a neutral observer noted that judges “unanimously declared that not a single lawsuit, criminal or civil, can be properly conducted if the interests of the Jews are involved.” Writing in 1914, American sociologist Edward A. Ross similarly commented on Jewish immigrants to America that “The authorities complain that the East European Hebrews feel no reverence for law as such and are willing to break any ordinance they find in their way. … In the North End of Boston ‘the readiness of the Jews to commit perjury has passed into a proverb.’”

Lindemann echoed Johnson’s description of the rise of Jewish power paired with Jewish involvement in major financial scandals. In Germany, Jews “were heavily involved in the get-rich-quick enterprises” of the period of rapid urbanization and industrialization of the 1860s and 70s. “Many highly visible Jews made fortunes in dubious ways . . . Probably the most notorious of these newly rich speculators was Hirsch Strousberg, a Jew involved in Romanian railroad stocks. He was hardly unique in his exploits, but as Peter Pulzer has written, ‘the . . . difference between his and other men’s frauds was that his was more impudent and involved more money.’”

Like Johnson, Lindemann delved back into the nineteenth century, writing that

In the summer of 1873 the stock markets in New York and Vienna collapsed. By the autumn of that year Germany’s industrial overexpansion and the reckless proliferation of stock companies came to a halt. Jews were closely associated in the popular mind with the stock exchange. Widely accepted images of them as sharp and dishonest businessmen made it all but inevitable that public indignation over the stock market crash would be directed at them. Many small investors, themselves drawn to the prospect of easy gain, lost their savings through fraudulent stocks of questionable business practices in which Jews were frequently involved.

Also like Johnson, Lindemann believed that accusations of fraud against many European Jews were not based on mere fantasy. With respect to the Panama Canal scandal of 1888–1892, for instance, Lindemann wrote:

Investigation into the activities of the Panama Company revealed widespread bribery of parliamentary officials to assure support of loans to continue work on the Panama Canal, work that had been slowed by endless technical and administrative difficulties. Here was a modern project that involved large sums of French capital and threatened national prestige. The intermediaries between the Panama Company and parliament were almost exclusively Jews, with German names and backgrounds, some of whom tried to blackmail one another . . . .

Thousands of small investors lost their savings in the Panama fiasco. . . . A trial in 1893 was widely believed to be a white-wash. The accused escaped punishment through bribery and behind-the-scenes machinations, or so it was widely believed. The Panama scandal seemed almost designed to confirm the long-standing charges of the French right that the republic was in the clutches of corrupt Jews who were bringing dishonor and disaster to France.

In many cases, the Jewish nexus of the financial scandal involved the idea that Jews implicated in financial scandals were being protected by other highly placed Jews. Lindemann: “The belief of anti-Semites in France about Jewish secretiveness was based on a real secretiveness of some highly placed and influential Jews. What anti-Semites suspected was not so much pure fantasy as a malicious if plausible exaggeration, since solid facts were hard to come by.” This secretiveness among prominent Jews is another example of the operation of the Talmudic Law of the Moser (which forbids informing on other Jews) and once again shows that illegal and unethical behavior is sanctioned within the Jewish community. The only crime would be to inform on other Jews.

Not surprisingly, however, the best contemporary discussion of Jewish financial power over the last two centuries comes from E. Michael Jones, publisher of Culture Wars and author of the 1200-page Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and Its Impact on World History (2008). He outdid himself by releasing in 2014 an even longer book called Barren Metal: A History of Capitalism as the Conflict between Labor and Usury. Naturally, because usury was a key topic, Jews are a primary topic of discussion.

Jones’ star is clearly rising, principally due to his presence on the Internet. Like TOO’s Kevin MacDonald, Jones ceaselessly appears in podcasts and is catholic in his willingness to appear on a wide range of shows.

With respect to Barren Metal, I will begin my consideration of Jews and usury from Chapter 64, “Napoleon Emancipates the Jews.” Previously, Jones had described many gentile financiers, but from Chapter 64 onward the pronounced Jewish role crescendoes to the point that, were the book divided in two and the second book to begin with Chapter 64, the sub-title would have to change to “Jews, Capitalism, and Usury.”

A main theme of Barren Metal is that “Capitalism is state-sponsored usury.” This is hardly a new idea, since German writer Werner Sombart explored the concept in depth in Jews and Modern Capitalism (1911). Jones describes Sombart’s idea thus: “capitalism is the philosophical and political sanctification of usury. Because money-lending, according to Sombart, is ‘one of the most important roots of capitalism,’ capitalism ‘derived its most important characteristics from money-lending.’”

Particularly with the rise of Protestantism in parts of Europe, usury lashed to state power altered the age-old economic foundation of the continent and Britain. In turn, this elicited the rise of modern anti-Semitism in Europe. For instance, Jones points to Wilhelm Marr, “the patriarch of anti-Semitism” (interestingly, three of Marr’s four wives were Jewesses), whose racial animus toward Jews may have masked an economic cause, which was usury. Marr wrote:

The burning question of our day in our Parliaments . . . is usury. . . . The political correctness of our Judified society helps it to sail by the reef which is the usury question, and as a result poor folk from every class become the victims of the Usurers and their corrupt German assistants, who are only too happy to earn 20 to 30 percent per month off of the misery of the poor. . . . In the meantime the cancer of usury continues to eat away at the social fabric, and the animosity against the Jews grows by the hour . . . so that an explosion can no longer be avoided.

In short, “This looting is, of course, to no avail because no force on earth can keep up with compound interest, which is the heart of usury.”

The climax of Barren Metal comes toward the end of the book in the chapter on the Vatican-approved periodical Civiltà Cattolica that in 1890 forthrightly addressed the Jewish Question. Far more than in modern America, enormous financial scandals in Europe of the era were directly and openly linked to Jews. In 1882, for example, the Union Generale bank collapsed and Jews were explicitly blamed for it. Its former head, for one, fumed that the Jewish financial power of the day was “not content with the billions which had come into its coffers for fifty years . . . not content with the monopoly which it exercises on nine-tenths at least of all Europe’s financial affairs.” This power, the man claimed, had “set out to destroy the Union Generale.”

In response to this collapse, famed writer Emile Zola published a novel in which a fictional young Catholic banker seethed at Jewish deceit. The Catholic character

is overwhelmed with an “inextinguishable hatred” for “that accursed race which no longer has its own country, no longer has its own prince, which lives parasitically in the home of nations, feigning to obey the law but in reality only obeying its own God of theft, of blood, of anger . . . fulfilling everywhere its mission of ferocious conquest, to lie in wait for its prey, suck the blood out of everyone, [and] grow fat on the life of others.”

While Zola employed fiction to make his point, Civiltà Cattolica used reason, facts and argumentation to chronicle how the Jews were able to foist their immoral ways (according to Christian mores) onto European society, and “the main way that the Jews achieved their hegemony over Christian societies was through ‘their insatiable appetite for enriching themselves via usury.’” The verdict? “The source of Jewish power is usury.”

From this central fact rolled well-known consequences:

Once having acquired absolute civil liberty and equality in every sphere with Christians and the nations, the dam which previously had held back the Hebrews was opened for them, and in a short time, like a devastating torrent, they penetrated and cunningly took over everything: gold, trade, the stock market, the highest appointments in political administrations, in the army, and in diplomacy; public education, the press, everything fell into their hands or into the hands of those who were inevitably depending upon them.

With control of gold came control of Christian society, particularly through the public press and academia, since “journalism and public education are like the two wings that carry the Israelite dragon, so that it might corrupt and plunder all over Europe.”

In the same chapter on Civiltà Cattolica, Jones discusses how the writings of one German, Father Georg Ratzinger, informed discussions in the Vatican periodical. As the name suggests, Fr. Ratzinger was indeed related to Joseph Ratzinger (his great-nephew), who became Pope Benedict XVI. The elder Ratzinger pointed directly to Jewish usury as the bane of Christian culture, which, when left unchecked, resulted in the enslavement of the surrounding Gentiles. Previously, of course, traditional Christianity forbade usury, meaning that the popes thus “deprived [Jews] of their ability to occupy the choke points in the culture.”

Ratzinger insisted it was foolish to abandon these tried and true Christian practices because Jews learned from their Talmud that “cheating the goyim was a virtue.” Linking free trade, capitalism and Jewish methods of conducting business, Ratzinger concluded that it was “to be expected that the Jews, who with centuries of practice became skilled in the deceptions of economic warfare and acquired the arts of exploitation to perfection, would take center stage under the regime of free competition.” It was not knowledge or ability, in Ratzinger’s opinion, that “makes the Jew rich and admired in society” but, rather, “deception and exploitation of others.”

Of course Ratzinger did not think Gentiles were totally blameless in these cultural and economic wars, for at a time “when Jews stand by even their own criminal element, we see Christian politicians and legislators betraying their own Christian faith on a daily basis and vying with each other to see who has the privilege of harnessing himself to the triumphal car of the Jews. In Parliament,” Ratzinger wrote, “no Jew need defend another Jew when their Christian lackeys do that for them.” (I wonder if there was a contemporary German term meaning “cuckservative.”)

Civiltà Cattolica is a treasure, as valuable now as it must have been over a century ago. I strongly encourage every serious TOO reader to familiarize himself with this tract, which can be found here.

Another fascinating topic Jones covers concerns the relationship between landed English gentry and Jewish moneylenders. “Stated in its simplest terms, the Jewish Problem involved the inverse relationship between debt and political sovereignty.” This antagonism toward growing Jewish power was common among the British aristocracy as well as politicians. The 1891 Labour Leader, for example, denounced the money-lending Rothschild family as a

blood-sucking crew [which] has been the main cause of untold mischief and misery in Europe during the present century, and has piled up prodigious wealth chiefly through fomenting wars between the States which ought never to have quarreled. Wherever there is trouble in Europe, wherever rumors of war circulate and men’s minds are distraught with fear of change and calamity, you may be sure that a hook-nosed Rothschild is at his games somewhere near the region of the disturbance.

An exemplar of this was the extended Churchill family, which fell into the clutches of Jewish moneylenders. Randolph, father of Winston and born in 1849, grew up in an era in which “spectacular bankruptcies” would plague aristocrats for much of the century. Much of this suffering was, of course, brought on by shameless profligacy among landed aristocrats, and Jones offers the Churchills as an example of this blight. Randolph—and in turn Winston—were very much in this mold, and fell straight into the hands of Jewish moneylenders, with profound consequences for Britain and all of Christendom by the time of Winston’s terms as Prime Minister.

As far back as 1874, the Churchill family was forced to sell wide swaths of land along with livestock to Baron Rothschild in order to settle a serious debt. Randolph, who had grown up amidst rich Jews with opulent tastes, made the mistake of thinking that he could indulge such a lifestyle without the necessary funds to back it. What he didn’t understand was that “he was on the wrong side of compound interest and they [his Jewish friends] on the right side.”

What followed was predictable. Randolph eventually contracted syphilis and lost large sums of money while gambling in Monte Carlo. In this instance, a Rothschild came to his rescue—but at a price. “The Jews who were supporting Randolph’s syphilitic fantasies and the extravagant lifestyle that went along with it . . . [were] willing to write off 70,000 pounds in bad debt because [Natty Rothschild] needed a friend in high places who would share Cabinet secrets that could be turned into hard financial gains.” Finally, consider this unsettling conclusion: In time, “the British Empire would become an essentially Jewish enterprise over the course of the 19th century.” By the end of the century, Jones concludes, “The British Empire had become one huge, Jewish usury machine, administered by impecunious, extravagant, perennially indebted, morally depraved agents like Randolph Churchill.”

Since Jones saw a reason to largely skirt over events from the 1890 publication of Civiltà Cattolica until the late 1940s, I’ll do the same. The founding of the Federal Reserve, for instance, is covered in a scant eight pages, the Depression is not much more than a footnote, and The Second World War is ignored. Jones resumes his tale with the rise of University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman, who was instrumental in creating the Chicago School of economics. Being helpful, Jones translates this development as: “The Jewish usurers’ Utopia which Milton Friedman promoted under the name of Chicago School economics was the mirror image of Communism, another Jewish Utopia, because both claimed that if their programs were implemented heaven on earth would follow.” Naturally, these claims were insincere (or could have been part self-deception) and Friedman’s advocacy of transferring public works projects into private hands, therefore, “was another looting operation.”

These assets that were the product of years of investment of public money and labor should, in Friedman’s view, “be transferred into private hands, on principle.” This public to “private” wealth transfer will soon be the focus of another discussion about Jews and money later in this essay.

First, however, I’ll mention in passing the subject of Jones’ Chapter 98, the leveraged buy-outs of the 1980s. Professor Benjamin Ginsberg was hardly alone in noticing that Jermome Kohlberg, Jr., Harry Kravis and many others involved in these buy-outs were Jews. As always, Jones does not disappoint in his ability to summarize this trend: “The concentration of the nation’s wealth in the hands of a few avaricious Jews has led to corruption of both discourse and culture.”

This era was the focus of my recent essay, Vulture Capitalism, Jews — and Hollywood, where I showed how Jewry hides in plain sight their ongoing looting of gentile wealth by creating blockbuster movies which feature no Jews, instead casting famous gentile actors as financial malefactors. (See Part 1 & Part 2 here.) Thus, I’ll pass over this important era in order to focus on another looting operation that is still almost invisible to the world’s public. This operation is the one a mostly Jewish cast imposed on a newly freed Russia that was ripe for exploitation at the hands of Jews “skilled in the deceptions of economic warfare.”

Jews, Oligarchs, and Russia

Of course white collar crime is one of the standard stereotypes about Jews and money, a description that seems to follow them wherever they go. Apologists for Jews claim that such crime occurs among non-Jews as well. The difference, however, is not only in their greater likelihood among Jews (see here for an academic treatment that addresses the issue — How do I find such obscure sources!), but, more importantly, that Jewish white collar criminals do not face censure within their own communities. Quite the contrary, it seems.

The following story regarding Russia is essential unknown in the Western world. I believe the first I ever heard of it was in a long 2006 blog by Steve Sailer where he wrote about the connection between Jewish networks, Jewish oligarchs, and the massive defrauding of the Russian people. This involved none other than the former president of Harvard, Lawrence Summers. It’s a long story, but Harvard paid $26.5 million to settle a suit stemming from various improprieties associated with Harvard professors. As Sailer illustrates, however, it is the Jewish aspect of the entire scandal that stands out. The principals of this scandal were Jews, and they were allegedly protected by fellow Jew, Harvard President Larry Summers. The upshot of the scandal was that the “reform” of the Russian economy “turned out to be one of the great larceny sprees in all history, and the Harvard boys weren’t all merely naive theoreticians.” Indeed, they ended up wealthy and managed to go on to other lucrative and important positions.

And guess what: The New York Times, Washington Post and Financial Times decided that this was not a worthy story. Gosh, why not? In the article, Sailer surmises that it was because of Jewish power, a not unreasonable assumption.

Sailer claims that he had not known about the Jewish identity of the “oligarchs” until he read Yale law professor Amy Chua’s book World on Fire. (When Chua correctly noted that six out of the seven of Russia’s wealthiest oligarchs were Jews, her Jewish husband quipped to her, “Just six? So who’s the seventh guy?”) These oligarchs had “paid for Boris Yeltsin’s 1996 re-election in return for the privilege of buying ex-Soviet properties at absurdly low prices (e.g., Mikhail B. Khodorkovsky was put in charge of auctioning off Yukos Oil, which owns about 2% of the world’s oil reserves — he sold it for $159 million to … himself).” Meanwhile, Jews in Russia represented about one percent of the population.

Sailer’s further observations only cast more light on the extent and value of these ethnic connections:

As I’ve said before in the context of exploring how Scooter Libby could serve as a mob lawyer for international gangster Marc Rich on and off for 15 years and then move immediately into the job of chief of staff to the Vice President of the United States, the problem is not that Jews are inherently worse behaved (or better behaved) than any other human group, but that they have achieved for themselves in America in recent years a collective immunity from anything resembling criticism [emphasis added].

Sailer goes on to discuss a number of Jewish reactions to Summers’ removal as Harvard president, ostensibly because of his views on sex differences, that square with what MacDonald has written on Jewish deception and self-deception, including the ability to frame all criticism, no matter how valid, in terms of an anti-Semitic animus. Thus, Harvard professors Alan Dershowitz and Ruth Wisse defended Summers, with Wisse asking, “Was anti-Semitism the driving engine of the coup [against Summers]?” Former lecturer Martin Peretz joined them in the suspicion that Summers’s strong support for Israel played a role in the attack.

- Michael Jones adds to the narrative by introducing yet another (((Harvard Professor))), one Jeffrey Sachs, who was tasked with helping nations in economic trouble transition to a modern capitalist economy. In this instance, according to Jones, it unfolded this way:

After orchestrating a coup d’état which deposed Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin dissolved the Soviet Union and invited Sachs to work his Friedmanite magic in Russia. Sachs was put in charge of Yeltsin’s band of Chicago Boys and together they orchestrated a looting expedition the likes of which the world had not seen since the Reformation. By the time it was over, 225,000 state owned companies would be auctioned off at pennies on the dollar of their real value. After Yeltsin opened the Russian economy to their predations, Chicago Boys like Stanley Fisher [it is actually Fischer], who was managing director at the IMF at the time, and Lawrence Summers … rushed in and sank their teeth deeply into the carcass of rich state owned companies…. The oligarchs then teamed up with the Chicago Boys and “stripped the economy of nearly everything of value, moving enormous profits offshore at a rate of $2 billion a month.”

Connecting the obvious dots, Jones concludes that “the looting of Russia was a Jewish operation from start to finish.”

This Russia story blends into an American story because of the Jewish nexus, and one of the best accounts of Jewish financial power — and its relationship to other forms of Jewish power — comes in the writing of retired professor James Petras. He has penned a series of books starkly exposing “the Zionist Power Configuration” that includes Jewish dominance in Western finance. In particular, his book, Rulers and Ruled in the US Empire: Bankers, Zionists and Militants, focuses on this, but he also addresses it in The Power of Israel in the United States, Zionism, Militarism and the Decline of US Power, and Global Depression and Regional Wars: The United States, Latin America and the Middle East.

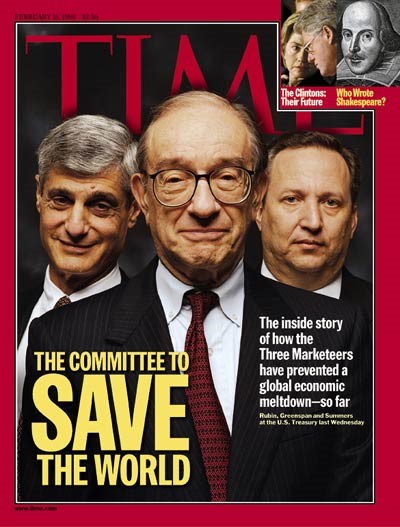

Here are some of the observations Petras makes: “Jewish families are among the wealthiest families in the United States” and nearly a third of millionaires and billionaires are Jewish. He also points to similar wealth in Canada, where “over 30 percent of the Canadian Stock Market” is in Jewish hands. Alan Greenspan’s tenure as the Chairman of the Federal Reserve is also linked to Zionist power, since Greenspan was “a long-time crony of Wall Street financial interests and promoter of major pro-Israeli investment houses.” (Greenspan was succeeded by coreligionist Ben Shalom Bernanke.)

Debunking the “high school textbook version of American politics,” Petras argues that “the people in key positions in financial, corporate and other business institutions establish the parameters within which the politicians, parties and media discuss ideas. These people constitute a ruling class.” Of the two groups cited by Petras — those in control of financial capital and Zioncons — both are so heavily Jewish as to constitute a single “cabal,” a word Petras uses liberally throughout his books.

Also, Wall Street supplies many of the “tried and experienced top leaders” who rotate in and out of Washington. At the top of the hierarchy, Petras finds the big private equity banks and hedge funds. Thus, political leadership descends from Goldman Sachs, Blackstone, the Carlyle Group and others. Goldman Sachs is a historically Jewish firm, Stephen A. Schwarzman is co-founder and current head of the Blackstone Group, while David Rubenstein is co-founder of the Carlyle Group and served in the Carter administration as a domestic policy adviser.

To get just a minor sense of the interconnectedness of Wall Street and Washington Petras is discussing — and to see its heavily Jewish ethnic nexus — note that during the second Clinton Administration, Robert Rubin served as Secretary of the Treasury and was succeeded by a familiar player — Larry Summers. Rubin worked his way to Vice Chairman and Co-Chief Operating Officer of Goldman Sachs prior to becoming the Secretary of the Treasury, and later became the Chairman of Citigroup and co-chairman of the board of directors on the Council on Foreign Relations.

With respect to the Russia angle, Petras also claims that former President Clinton and his economic advisers backed the regimes that allowed the plunder of Russian wealth. Though relegated to an endnote, he names Andrei Shleifer and Jeffrey Sachs as those involved. What is relevant here is the ethnic connections going to the top of American society that validate Petras’s emphasis on the combined power of Zionism, media and financial control.

The next link to this story was entirely fortuitous. I was working on a project entirely unrelated to Jewish influence, but lo and behold, there it was again. For reasons too boring to describe, I was doing research on trade expert Clyde Prestowitz, who came to the world’s attention with his 1988 book Trading Places: How We Allowed Japan to Take the Lead. This was followed by other big books such as Rogue Nation: American Unilateralism and the Failure of Good Intentions (2003), Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East (2005), and The Betrayal of American Prosperity: Free Market Delusions, America’s Decline, and How We Must Compete in the Post-Dollar Era (2010). In particular, the three books written after 2000 concern us.

Prestowitz describes himself as “The product of a middle class, conservative, rock-ribbed Republican, superpatriotic, born again Christian family,” so I’ll take his word for it that he’s not Jewish. A former high-level businessman turned trade official in the Reagan Administration, Prestowitz succeeded in carving out a niche for himself as one of the most insightful commentators on America business and trade. In 1989 he established a think tank, the Economic Strategy Institute (ESI), so I have to assume he’s worldly enough to understand the strictures surrounding talk about Jews, especially when it’s negative.

In one of his books, Prestowitz writes of America that “the vast bulk of working people (who, of course, are also consumers) lost ground. Between 1980 and 2005, U.S. productivity rose 71 percent. Yet real compensation (including benefits of nonsupervisory workers (80 percent of all workers) rose only 4 percent. In the tradable manufacturing sector, productivity rose 131 percent while compensation climbed only 7 percent. This was in stark contrast to the period from 1950 to 1975 when worker compensation rose 88 percent while productivity doubled.”

He locates the reason for this in the fact that the one industry America has promoted over the past thirty years is finance. “It is so striking that I fear we must call it for what it has been — a clear industrial policy to target development of the financial services industry.” He then cites figures for why. In the ten years ending in 2008, “the finance industry spent $1.78 billion on political campaign contributions and another $3.4 billion on lobbying.”

Here Prestowitz, perhaps unwittingly, enters into controversial territory when he begins to construct the outlines of a theory that sound suspiciously like the old “anti-Semitic canards” that blame Jews for the ills laid onto “real” Americans (or Germans or whatever). As he writes, “We need to understand that the interests of Wall Street, and therefore much of Washington, have not been and will not be those of Main Street.” (Cue now Tucker Carlson’s recent segment called “Hedge Funds Are Destroying Rural America.”)

The bulk of this argument is made in chapter four of Three Billion New Capitalists, “Goldilocks and Bubbles: The Faith of Efficient Markets.” A staunch critic of free-trade theory as [allegedly] practiced by modern America, Prestowitz lays the blame for America’s loss of prosperity at the feet of “The Three Apostles: Greenspan, Rubin, and Summers.” He notes how in 1989 and 1993, financial instruments that would play a major role in the meltdown of 2008–09 were exempted from government oversight. Greenspan in particular was passionate about getting the government out of the way. “In fact, Greenspan largely halted the Fed’s active oversight of the banking industry.” Joined by Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin and subsequent Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, “the three mounted an aggressive campaign to halt any efforts to regulate trading of new derivative instruments.”

Further crises erupted, all of which involved “The Three Apostles.” Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), a hedge fund, faced the prospect of losing a staggering $1 trillion dollars that it had borrowed from the largest American banks. “It threatened to freeze world money markets and precipitate a 1929-style crash and perhaps another depression.” Awkwardly, Greenspan, Rubin, and Summers “were in the process of halting a measure that would have put some constraints on the very kind of risky derivatives trading that was bringing LTCM to its knees.” Meanwhile, they continued to discourage the oversight of Brooksley Born, Chairwoman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Summers had even phoned her and sharply criticized her actions. This was followed by Greenspan, Rubin and Arthur Levitt of the Securities and Exchange Commission pressuring Congress to straightjacket Born.

More Reason to Trust the Media

This persisted into 2000, as Greenspan continued to insist that Wall Street should be trusted and left to its own devices. “With those assurances, Congress went ahed and stripped the CFTC of responsibility for derivatives, and President Clinton signed the bill into law in December 2000.” Meanwhile, Ms. Born quietly left government service.

A more explicit account of the pressure brought to bear on Born can be found in Kevin MacDonald’s blog Self-Deception and Guruism among Jews, where he writes how psychoanalysis was

perhaps the greatest intellectual fraud of the 20th century — a set of beliefs that explained everything but had only the most tenuous connection to reality and an ideology that empirical research was for bean counters. The same thought crossed my mind while reading Thirteen Bankers, by Simon Johnson and James Kwak. Near the heart of the financial meltdown was the towering self-confidence of Larry Summers, Robert Rubin and Alan Greenspan in opposing any regulation on the derivatives market. Summers seems to be pivotal. When Brooksley Born, head of the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, proposed that some thought should be given to regulation, Summers reportedly said “I have thirteen bankers in my office, and they say if you go forward with this you will cause the worst financial crisis since World War II.” As Johnson and Kwak note (p. 9), we don’t actually know if there were any bankers in Summers’ office; “more likely he came to his own conclusion.” The point is that Summers had an unshakable faith th