Thoughts of a Semi-Self-Quarantiner, by Fenster

Prelims

The problem with the future is that it hasn’t happened yet. I had a hard time explaining this to my finance students in a discussion of accounting and budgeting. Accounting is replete with risks and uncertainties, but for the most part they are risks and uncertainties associated with whether you put things that already happened into the proper and most useful buckets. Budgeting has all those risks, combined with the much more significant risk that things have not happened yet, and that your tool for managing the future my not only be off as a result of internal factors but external factors not under your control.

Figuring out what to do about the virus is a future-oriented task and as such it benefits by, but is also constrained by, projections about the future. It is wise to take both benefits and limitations into account explicitly in fashioning policy but there is, if you will, a limit to this. It is hard to make allowances for known unknowns. Harder still to make allowances for unknown unknowns. Harder yet again if the object of high uncertainty is of grave consequence, for it is here that the “fat tails” that Taleb discusses reside. Sometimes the hardest things to make subject to probabilities are the ones that will kill you if you are wrong.

It is for this reason that the heart of leadership will always be characterized by hard to quantify words like “prudence” rather than fake precise words like “efficiency”. One of the reasons we bend to the need for leaders is that from time to time we need someone to deal with fat tails.

The data are there. Some high quality, some low quality, some missing, some faked. The projections can be cranked out. But the uncertainties create options and paths that do not answer themselves.

The cost-benefit can be done, though it is near impossible given the moral, technical and political difficulties associated with fixing the value of a human life. And which life? Maybe that budding nuclear scientist that efficiency says to spare. Maybe aging, ailing, failing grandpa living up the stairs, who can only rely on the charity and care that is part of our tradition.

So what about that virus? The answer is hardly a given, and in the end will express something of the character of the people and the leaders they have in place to handle these kinds of problems.

This is all to say the best path is inextricably bound up with questions of values, habits and culture. Public health, like the politics embedded in it, is downstream from culture, and culture will act both as a judge of appropriateness and risk and as a constraint on actual behavior.

A doctoral candidate who is in Shanghai has written about his optimism over the ability of cultures to rapidly adapt, and that crushing the virus by flattening the curve is possible as long as people adapt.

I’m sitting in Shanghai and life is perfectly pleasant. Without imports from abroad there would be no cases at all. But freedom of travel and assembly is *selectively* curtailed. Society has got its act together for this purpose.

It’s actually a simple formula. The better organized society is towards this purpose, the less freedom needs to be curtailed to achieve effective control of the virus. What is happening effectively in China is this is being done dynamically in response to local conditions. . .

Painfully and messily, behavior change is happening in Europe and America. It will bring the virus replication under control. And then it will be possible to rebuild freedoms step by step. That is the correct answer.

That’s a nice thought but might it not be possible that different cultures will not adapt, or adapt as quickly as Chinese culture has done? There are benefits and drawbacks to living in a culture that puts the individual first. One of the drawbacks is that it may be slower to respond to challenges that put a premium on the ability to adapt rapidly in ways that align with collective, not individual, aims.

Cultures change when faced with challenges to their underlying values but such change is typically slow, and happens only when there has been some Darwinian thinning of ideas or even the people that hold them. So count me a skeptic on whether Americans will lurch effectively toward Chinese ways.

Lenin (b. 1870) posed the question “what is to be done?” My initial answer comes from the American management theorist Mary Parker Follett (b. 1868). Look for the Law of the Situation. Often (though not always) the path forward is made clear through a deep understanding of the current situation.

That’s a bit Pollyannish to be sure, and Follett herself came to the notion in trying to find ways to make the giving of orders more palatable. But in the process of making for healthier interaction between superiors and subordinates she brushed up against an important truth: managers should spend more time and attention understanding the situation. Not only will it make the order go down better if it is seen as neutral thing. There is also the possible benefit that the situation may actually yield secrets about the future.

Of course people do this every day, including with respect to the virus. But it is wise to constantly check and recheck assumptions.

We are approaching the world of Daniel Kahneman here. Most of our thinking is less thoughtful than it should be. We rely on useful generalizations, rules of thumb and heuristics and most of the time they work. But nature provided a fallback in what Kahneman calls System 2: from time to time you need to do a counter-intuitive reality check on the heuristics you rely on most of the time.

Note that in Kahneman’s view this is just part of the human dilemma. We need to simplify. Sometimes our rules of thumb won’t work. We don’t know exactly when to proceed and when to reflect. That may require good intuition. How do I feel about things? Are my models working or do they need a good roughing up?

When as an amateur you are pitched headfirst into a crisis, one in which by its nature you have an interest and play a part, you cannot help but rely heavily on heuristics, many of which may end up thin reeds for action. This problem is compounded when the phenomenon in play is fast moving and poorly understood by the experts, with the result that you get the pronounced impression that they, too, are improvising and building models on sand.

Take the concept of “flattening the curve.”

We see a bell curve indicating the life cycle of the virus without mitigation. The we see a wider but shorter bell curve of the same volume, this one cresting just under a line indicating hospital ICU capacity. Brilliant! It went viral and now “flattening the curve” is a rallying cry.

But whether flattening the curve is useful in practice is almost wholly dependent on Follett’s “situation”. We are drawn to the chart like moths to a flame. But perhaps this is one of those times we should say to ourselves “wait a minute. That sounds good but is it?”

Joscha Bach has written an article for Medium in which he says no. Perhaps it is time to take a Kahneman pause and rigorously vet our heuristics. And to ask the Follett question: what is the situation? And can we derive a Law of the Situation from an understanding of it. It does not have to be an Iron Law–just a better law, one that takes account of counter-intuitive self-directed reflection and analysis?

Bach argues that if you employ the conventional wisdom assumptions on rate of contagion and mortality the growth in infections and, in turn, in ICU stays, will be several orders of magnitude greater than out system can handle.

The curve without mitigation overwhelms the hospital capacity line so greatly that it makes no sense to even try to flatten it with our current mitigation approach. Don’t preach flatten the curve without putting the actual numbers in. To do so only wastes precious time as the exponential growth continues. Bach argues for an immediate switch to Chinese-style hard measures on the grounds that since they worked there they have a fighting chance of working here, and we delude ourselves with all the talk of flattening the curve.

But two can plan the game of What is the Situation? Does Bach get the situation right?

Damned if I know.

Questions

In discussing the virus from the comfort of home I just got the preliminaries out of the way with here, ending with the troubling conclusion that it is hard to know with great certainty what the hell is going on.

Maybe there’s no need to know. But amateurs are citizens, too, and up to their necks in the public health questions since they are, well, public. That fact, combined with the intuited sense that the experts don’t have their act fully together yet either, argues for active amateur engagement. So in that spirit here are a bunch of questions I have. Questions, mind you, not answers, and offered in the spirit of intellectual modesty and policy prudence.

Flattening the Curve. How good an approach is flattening the curve? As I wrote in the last post one can challenge the concept on the grounds that it creates unreasonable expectations about not breaking ICU capacity given assumptions made in connection with three main variables: contagion rate, mortality rate and efficacy of our relatively non-intrusive mitigation approach. I will get back to this question at the end.

Assumptions that Drive the Model. Related: how good are the contagion and mortality assumptions that form the basis of most of our thinking? The WHO has pegged mortality in the 3+ % range–scary, if you assume widespread contagion. Folks I respect like Greg Cochran says it is likely worse than this.

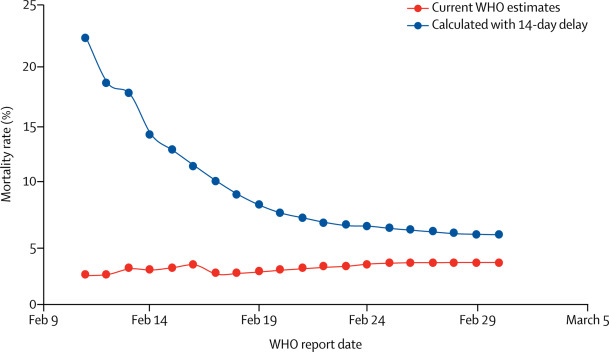

This pessimism was recently backed up in an article in Lancet. The authors note that deaths follow onset by several weeks and so a more appropriate way to measure mortality is to use deaths in the numerator but to use in the denominator not cases on that day but cases reported two weeks before. Given that the curve was sharply upwardly sloping at the outset, the use of a smaller number in the denominator pushes mortality rate way up.

If we employ even more pessimistic assumptions flattening the curve gets harder, and may require draconian measures to tame.

But is the pessimism warranted? The Chinese maintain their vigorous contact tracing means they caught nearly all the cases. Various data on illnesses not immediately connected to COVID-19 suggests few actually turned up to be COVID-19. Thus (unlike the situation in the United States, where total cases may be much higher than those identified to date) it can be argued that mortality rate in China can be inferred fairly well on the basis of known cases on file.

But did this assumption hold at the outset of the outbreak? What confidence do we have that pushing the date of earliest deaths back a full two weeks will not land us in territory in which the actual cases would have been undercounted relative to the deaths that would be later connected to them?

Added to that is the suggestion, advanced by the WHO and presumably endorsed by the Chinese, that the high initial mortality rate had something to do with the health system being unprepared and surprised.

As of 20 February, 2114 of the 55,924 laboratory confirmed cases have died (crude fatality ratio [CFR2] 3.8%) (note: at least some of whom were identified using a case definition that included pulmonary disease). The overall CFR varies by location and intensity ofmtransmission (i.e. 5.8% in Wuhan vs. 0.7% in other areas in China). In China, the overall CFR was higher in the early stages of the outbreak (17.3% for cases with symptom onset from 1-10 January) and has reduced over time to 0.7% for patients with symptom onset after 1 February (Figure 4). The Joint Mission noted that the standard of care has evolved over the course of the outbreak (emphasis added).

And then consider this graph, from the WHO’s latest Situation Report.

The mortality rate in Hubei (Wuhan’s province) is far higher than the rest of the country. Moreover Hubei evidences by far the largest number of cases overall–about 85% of the total for all China. An examination of the mortality rates in the other 15% of the country reveals them to be quite low. The mortality rate in the province with the next highest number of cases (Guangdong) is .5%–a normal flu number. Mortality rates in the other provinces can be a bit higher but not overly, and some provinces report no deaths (such as Shanxi, with 133 cases).

Take a look at the WHO’s graph on case fatality ratio in Wuhan, Hubei outside Wuhan, China outside Hubei and all China.

We see extremely high mortality rates at the outset in Wuhan, driving up the number for China overall that is embedded within it, and the experience of which will affect all manner of summary data down the road. Neither Hubei outside Wuhan nor China outside Hubei show a similar initially high level of mortality.

Isn’t there something odd about the Wuhan curve? The month of January, which is the main period captured here, was a period in which new cases (and according to the Chinese essentially all cases) were rising rapidly in the now familiar exponential way.

Yet all through this period mortality in Wuhan was dropping.

I am not sure what this suggests.

This recent article–apparently scholarly but not yet peer reviewed–takes its own look at Wuhan.

We found that the latest estimates of the death risk in Wuhan could be as high as 20% in the epicenter of the epidemic whereas we estimate it ~1% in the relatively mildly-affected areas. Because the elevated death risk estimates are likely associated with a breakdown of the medical/health system, enhanced public health interventions including social distancing and movement restrictions should be effectively implemented to bring the epidemic under control.

But that, too, seems odd. Maybe Wuhan’s mortality rate is mathematically around 20% but before advancing that as a mortality rate suitable for export one should understand its meaning. It does not seem likely that it would have been a function of the breakdown of the system–breakdowns are evident when things get worse, not better.

Additionally, while social distancing and movement restrictions may be justified as a way to avoid stress to the health care system reducing contagion in and of itself would not seem to lead to a lower death rate, all else being equal. Most people who contract the virus will not need intensive medical care and will not die. Death comes to two kinds of people who get as far as critical care: those the medical system could not save (about half, in China’s experience) and those who get better after intensive care, whether or not they may have recovered anyway (another half). You want a robust intensive care system to save the 50% that can be saved, given existing standards of care. The others would have died no matter what.

So perhaps the high initial levels of mortality in Wuhan are not a function of an overwhelmed system but something of the opposite: an underprepared and surprised system. Maybe the system had the capacity to save a high percentage but did not know how to do it.

In turn that suggests the possibility that the 50% chance of death after intensive care admission may be too high as a going-forward assumption, as it may have the one-time bad experience at the outset embedded in it. China’s experience after critical care in ICU is 50/50 overall–but did that change over time? And what is the current ratio, reflecting more experience, less surprise and the possibility of more robust protocols and pharmaceutical interventions?

Add to that the idea that China may not have mastered the problem of the denominator to the extent they claim, especially at the beginning of the outbreak. That too may lead to the prospect of a better number from a looking-forward perspective.

Then consider again the numbers on the chart above, the ones that showed very low mortality in the 15% of cases outside Hubei. What is the explanation for this in light of the discussion above relative to Wuhan?

One might argue that it is all a matter of time lag–provinces other than Hubei will soon hit those high levels–or they would have, if draconian restrictions were not put in place. I don’t know the sequence here and am not sure how to find it. But consider: the mean time in China from onset to serious conditions necessitating an ICU is several days, and when death comes it comes between two and eight weeks of onset. I believe I have read a mean value there of three weeks.

Granted the community spread of the virus was most intense in the province where it originated. But would not the other provinces in China now have sufficient time and experience under their belts to see a rush to ICUs and to Wuhan-style mortality rates?

Mortality in the United States. We have tended to take assumptions from the more intensively studied China and, to a lesser extent, Italy, and pump them into our experience. Here, optimists say we can do a good enough job flattening the curve and pessimists say hell is about to break loose.

But what do we know of our own numbers? I know there are places reporting more deaths than the CDC but since that is our official agency let’s go there.

As of this morning (the page may have changed when you visit) the CDC reports 41 deaths in the United States. While other sites provide cumulative data I cannot find any on the CDC site. But I do know this: the number has been 41 for at least three days running now, and was not much lower in the immediately prior period when I started looking. And recall that something over half of that number is due to one cluster in one life care center in Washington State. Deaths associated with that center unfortunately continue to come in day by day. But one way or another deaths are low nationally, and no move to exponentiality is evident.

By contrast our number of known cases is going up more sharply, and may go up like a rocket if the testing regime about to take effect discovers a lot of new cases. If that is the case we will have a serious denominator problem. All the more reason to focus on deaths, until such time as we can confidently produce a useful denominator for mortality rate. Until them while mortality rate might typically be a lagging indicator it may have to serve as a leading one.

Why no exponential growth yet? One can argue 1) law of small numbers and 2) it is early yet–you’ll see. But keep in mind that in China onset to death started happening in two weeks. We have just over that experience in the United States data, and should start to see exponentiality in deaths that to some extent mirror cases.

And if, to choose a recent example, Ohio has as its health director suggested over 100,000 hidden cases and not the 5 it had on the books, would we not be seeing an exceedingly large number of Ohio deaths starting around now? If deaths occur (per China) from weeks two through eight Ohio at a mortality rate of 3.5% Ohio might expect 3,500 deaths between now and a month and a half from now. Not saying it won’t happen; not saying it will. But if we are going to plot China’s experience on ours it is an important thing to keep track of.

ICU stress in the United States. And then take the issue of ICU stress. As discussed above the experience in China was that the gap between onset and need for intensive care was very small, a matter of a few days. We have had more than that time go by with United States cases. If Ohio had 100,000 cases when the state official put the number out surely some significant percentage of them would date back days or even weeks. And if, per China, 20% of cases require ICU-style care, we should have seen 20,000 new ICU-demand cases in Ohio already. Have we? Maybe I missed something but I seem to think the ICU crisis is around the corner, and not here yet.

The denominator problem. China says it counted all its cases and its contagion and mortality rates follow that conclusion. But if we accept that conclusion we are forced into the near-inevitability in the US of system collapse (per the Medium article cited in the last post), especially if — yikes! — our known cases skyrocket after testing. We would then also have to explain why death rates and ICU admissions do not seem to conform to China data expectations.

Perhaps we will find a ton of new cases–but then unless deaths spike too in short order we are left to explain why the virus here seems less deadly.

Perhaps we will not find many new cases. In that instance the cases and death rate may resemble the rate seen in China–but then we are left to explain the lower contagion rate.

I don’t want to get conspiratorial about it but it is not a given that everyone worldwide is equally susceptible to infection. The WHO said it was a reasonable inference to make but the analysis has not been done, and China may not be the ideal place to do it. The United States is a very diverse society. I wonder if data collection will be limited to an analysis of gender, age and pre-existing condition, or if other variables are taken into account. Maybe groups differ by susceptibility, or even likelihood of death. If that were not possible we would not have nations working on biological weapons capable of discrimination–not to say that is at work here!

Who is at risk? The China data suggest that, at least in China, the elderly and/or those with pre-existing conditions are more at risk, and greatly so. This comprehensive report on the experience in China has interesting data in this regard.

The case fatality rate from age 0 to age 40 is .2%. Ages 40-50 is .4%. Spitting distance of noal flu. Age 50 it jumps to 1.3%. Only begins to get severe at the next three breaks: 3.6% (60-69), 8% (70-79), 14.8% (80+ ). In terms of numbers, around 80% of deaths occurred among those 60 and above.

Various pre-existing conditions are also analyzed, and found to be important predictors of mortality. But the data are not displayed at a level of detail that breaks out the effect of pre-existing condition on age brackets. Suffice to say that some of the cases connecting to pre-existing condition will be found below age 60, further increasing the gap between older and younger. Additionally, while a good deal of the pre-existing condition cases will be connected to older individuals, to the extent their effect is pronounced it becomes easier to identify the elderly with the highest risk of mortality.

And here is data by period. Note these data are in keeping with the Wuhan discussion above. Wuhan comprises the great majority of cases (85%) AND in Wuhan and Wuhan alone we had the reverse curve going on: many more deaths initially than later.

What is to be done? The solutions to date seem to be of two types. The first is “contain the contagion, flatten the curve, crush the bastard” seen in most countries in various forms. We look to control the behavior of all mostly to reduce the deaths of the few that are most likely to perish.

It is not that we are unmindful of the travails of a young person getting flu-like symptoms, or even a middle aged person spending a few days in the hospital with no great risk of death. But the main game here is preventing deaths, which means preventing the deaths of those who are most likely to die. The way we limit deaths is through the reduction of contagion in the population. The Chinese opted for intrusive measures; the West, so far, less so. But both are aiming at the same thing: contagion as a proxy for limiting death.

The second is the “controlled burn” approach, the path taken by the UK. Here the idea is to sever the connection between contagion and mortality. The contagion can be at any level among those who are highly unlikely to die from it. But protect the targets.

Is this feasible? Once again we come back to Follett’s Law of the Situation. What does the actual situation suggest?

One way to reason through to an understanding of a situation is to start with an exaggerated version of reality and tweak it. As a thought experiment consider a virus that manifests itself as a regular flu with the exception of two known individuals: Trump and Pelosi (selected to reduce bias in favor of preference for death). If these two catch the bug they die.

- we know precisely who is at risk of death.

- we know everyone else gets the regular flu

- we know the measures needed to protect Trump and Pelosi. They are affordable (only two people) and achievable (assuming the virus is not The Terminator and can be stopped with reasonable effort.

In that case there is no doubt we undertake controlled burn, combined with whatever efforts are required to shield the targets from the necessary firestorm outside.

That is not the actual situation of course. But how far is the real situation from the ideal? And at what point do you abandon controlled burn for crush the bastard?

First, consider the knowledge of targets. The world does not cleave into two neatly, with those who are going to die with red shirts and those who will not die with blue shirts. But we do know a lot about who the red shirts are. You will catch most of them by considering age. The elderly are a growing part of our population but they are discrete, and fewer in number at the higher age ranges.

Moreover a high percentage of these people live in managed situations. That works the wrong way when the virus is let loose, as happened in Washington State. But if one is going to effect very tight Chinese style movement restrictions and hygiene safeguards it is a lot more efficient and economical to focus on the vulnerable already living in conditions that can be tightly controlled.

In turn it could be the focus of public and community efforts to identify and manage others not living in such communities–the elderly living alone or with family, or younger people with serious pre-existing conditions.

What about those who are then not tightly controlled, and are left to socialize as they will? Some will contract the virus as they would the normal flu, and some would die as with the flu. Those numbers will be somewhat higher than the flu based on China’s experience. But provided we did a good job identifying those inside the firewall those opting to live outside of it might take the risk.

Further, nothing stops the careful young healthy person from self-quarantine as desired. They may have a marginally higher rate of infection if the virus rages outside and their living situation is not totally buttoned up. But the most likely worst case is that they get a nasty flu if a visiting friend sneezes unexpectedly on a visit.

The younger and healthier may be willing to take the risk. First, lifestyle is not crimped! But in addition coming down with a bad flu today may confer immunity for later. The WHO report says further study is needed on whether exposure confers immunity but it apparently did in the Spanish Flu epidemic, the first year of which was bad but the second year of which was the world-killer. The younger and healthier might prefer a nasty bout of flu this year over much more certain death next.

And from a collective point of view if exposure results in immunity the more infected this year on the free side of the firewall the less kindling the flu has to spread. And that logic applies with more force to the denial of kindling to any second year virus with potentially much greater lethality.

All good policy decisions–by which I mean all difficult and consequential policy decisions–are close run things, with the answers not obvious. They may not always be 49-51 propositions but seldom are they 99-1 slam dunks. Whether controlled burn is preferable to crush the bastard depends on a lot of things: how far a messy reality differs from whatever model is trotted out in support, the lack of good data that may compromise any attempt to think in a more subtle way, the fact that some issues (such as public health) unfold in a dynamic environment, replete with multiple actor game theory implications that produce their own uncertainties.

But that’s why we have leaders–to make these kinds of calls. Right now I am attracted to the controlled burn notion based on my own read of data and situation. But I am an amateur, a citizen, and not the leader/decision maker. Our leaders do not seem to be following the UK path of controlled burn and are doubling down on crush the bastard. Since I wish for a good outcome more than I aspire to be right I hope that is the right call.

About Fenster: Gainfully employed for thirty years, including as one of those high paid college administrators faculty complain about. Earned Ph.D. late in life and converted to the faculty side. Those damn administrators are ruining everything.