Review: the Trayvon Hoax, by Huntley Haverstock

Back in 2012, the Trayvon Martin case was my first awakening as a budding young leftist to not only how wrong, but how blindly and aggressively wrong the left could be in its crusades. I remember studying the details of that case before it ever became national news. By collecting a series of locations on the Twin Lakes map and correlating them to various timestamps, it became clear very quickly that Zimmerman’s version of events was correct. It was easy to do this because almost everything happened on recordings. There was only a gap of less than a couple of minutes between the end of Zimmerman’s phone call to dispatch, and the 9-11 calls reporting screams that ended in the sound of gunshot.

The crux of it came down to this: we knew about where George Zimmerman parked his car before stepping out to tell dispatch which way Trayvon Martin was running. We knew about where he was when he ended this phone call, because he reported the address on a nearby street sign. And we knew where Trayvon Martin was running to: his father’s fiancee’s home. These three points form the shape of an L turned 180 degrees to the right, with Zimmerman’s car at the top-left point, Trayvon’s destination at the end of the bottom leg, and the place where Zimmerman ended his phone call near the right-angle turn. The Black Lives Matter activists would have us believe that Zimmerman stalked Trayvon down in the street, provoking and justifying Trayvon’s panicked reaction. But Zimmerman maintained that he had entirely left Trayvon alone and was walking back to his truck when he was jumped and pinned to the ground while Trayvon attempted to slam the back of his head into a concrete curb.

Guess where the altercation took place? It wasn’t in between where Zimmerman ended the phone call and Trayvon’s father’s fiancee’s home. It was in between where he ended the phone call and his truck—which means the facts completely supported his version of events.

You may remember that in the initial outcry over the case, what would soon become the Black Lives Matter movement claimed they just wanted to see the case brought to trial. In the beginning, they presented the matter as if they were open to all possible outcomes, and simply found it astonishing that the case wasn’t tried in court. In retrospect, we know how unhappy they were with the results of their “success” in that endeavor, and it’s clear how fast and heavy mission creep took over.

The key event that transformed this from a small local case in Florida that never even made it to court to a defining national event was the discovery by Martin family lawyer Benjamin Crump of a witness whose testimony was able to bring the case to trial: Rachel “DeeDee” Jeantel. Supposedly, the girlfriend of Trayvon Martin, who was on the phone with him for the entire lead-up to the altercation that ended in Martin’s death.

If you followed that case as closely as I did, it was obvious that something was extremely suspicious about “DeeDee’s” testimony from the very beginning. Benjamin Crump first claimed the star witness he found was 16—she turned out to be 18. Investigators were obviously frustrated by how difficult it was to pull a coherent sentence out of her. Crump sounded as if he was leading the witness even on the tapes we have recordings of—at one point telling her he’s going to start the recording over starting from what she just said and asking her to repeat it “slowly, and clearly.”

A letter was presented at trial that was supposedly given to Sybrina Fulton by Rachel Jeantel, recounting her version of events. The letter was written in cursive, and signed in print at the bottom with the name “Diamond Eugene.” When Rachel was asked in court to read this letter out loud, she admits that she is unable to do so because she doesn’t know how to read cursive. These discrepancies were supposed to be explained by Rachel having dictated the letter to someone else who wrote it for her (although who supposedly wrote it for her was never actually named), and “Diamond Eugene” being a nickname.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve never heard of anyone writing a letter to someone by dictating it to someone else. Why have someone write a letter that you can’t even read over yourself before handing it to the recipient? Rachel couldn’t read or write cursive, but certainly she could read and write in print. Sybrina Fulton clearly hesitated for a long time before handing this letter over detectives. When asked why, she explains that she considered it “personal.” But the short letter has nothing most of us would consider “personal” in it at all—it’s just a rote summary of the Benjamin Crump version of events that was ultimately rejected by the courts.

While Rachel Jeantel is recounting (or at least being dragged through a recounting of) the story of how she came to introduce herself to Trayvon Martin’s step-mother Sybrina Fulton, the investigators at one point ask, “And then you said to her, ‘My name is Diamond Eugene?’”

Jeantel’s response was telling at the time, and is even more telling now. She looks with her signature deadpan blank stare at the investigator and says, “Don’t say my name. Don’t say my fake name. Don’t say my age. Don’t say my fake age.” (Recall that Trayvon Martin’s girlfriend was announced as a sixteen-year-old before the eighteen-year-old Rachel Jeantel appeared to testify.)

Near the end, Jeantel covers her face with her hands and says, “I feel so guilty.” Investigators ask, “Why?” and she says, “Cuz I ain’t know about it. I ain’t know about it.”

Nobody gave any indication they knew what she meant, and they didn’t press for any further explanation. Didn’t know about what? She obviously knew about the altercation between Martin and Zimmerman, because she was supposed to have been on the phone with Martin the entire time—that was the whole point of her being called in as a witness, was it not? So what did she feel guilty for not knowing about?

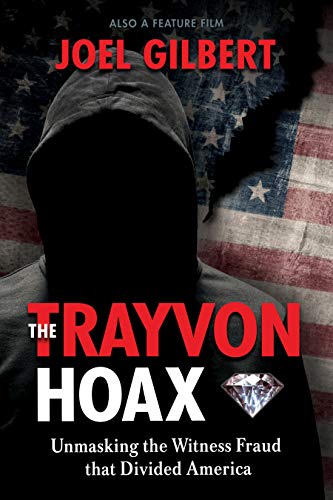

A documentary released by Joel Gilbert on April 26, 2020, titled The Trayvon Hoax: Unmasking the Witness Fraud that Divided America, fills in the missing pieces.

To be perfectly clear, it is beyond question now that Rachel Jeantel was not on the phone with Trayvon Martin on that fateful night, because she was not his girlfriend. Thanks to Gilbert’s work, we know exactly who his girlfriend was.

To be perfectly clear, Gilbert’s style as a documentarian is hokey. He drags what could have been an extremely compelling case into a two-hour snoozefest, complete with lectures on racial unity and dramatized videos of him slinging books around in frustration at his initially fruitless efforts to dig through yearbook pictures from schools Trayvon attended. His past work includes one documentary claiming Obama’s biological father is Frank Marshall Davis

But the facts Gilbert exposes in The Trayvon Hoax are public information, easily accessed from Florida records by any FOA request. And they paint a picture that is beyond dispute. Rachel Jeantel was not on the phone with Trayvon Martin on that fateful night. Rachel Jeantel was not Trayvon Martin’s girlfriend. I assumed before that investigators were prodding Jeantel along to give the right story just because she was so obtuse that they had trouble getting the version of the story out of her that they needed. Now I am left without a single shred of doubt that she was coached from nothing—because she was an outright imposter.

If Gilbert is lying about the information he received by FOA, then he will be easily exposed in a short matter of time. But I really doubt that Zimmerman would be leading a major lawsuit over these revelations

Gilbert may be willing to engage in baseless speculation for profit, but he doesn’t strike me as a suicidal idiot willing to alienate even the small base of people willing to indulge him. We don’t need to think Gilbert is a revolutionary thinker to realize the case he makes here is true. It did take him 8 whole years to achieve what anyone could with a few simple public record checks could, anyway. We just need to think he hasn’t faked the documents he displays as support to his points—which anyone could easily check by simply requesting the same records. If the records show what Gilbert shows here, the case is absolutely slam-dunk.

Gilbert shows us an unredacted version of the investigative report that tells how investigators acquired Rachel Jeantel as a witness. Sylvia Fulton first sent them to an address that apparently turned out to be the wrong address, because at that address they were redirected to a completely different one, where they found Rachel Jeantel. Guess who turns out to have lived at that first address? A girl named Brittany Diamond Eugene. Diamond isn’t her nickname, something that could be mistaken or easily covered up—it’s her real, official, legal name. Traffic incident reports in the state of Florida provide us with printed signatures that can be easily confirmed by anyone and show a printed signature that looks identical to the one on the letter that Rachel Jeantel couldn’t read in court.

Text records, which are available by FOA as part of the trial evidence, make it abundantly clear that this Brittany Diamond Eugene is who Trayvon was regularly texting and calling in the weeks leading up to his death. Photos sent by text leave no room at all for doubt, as if there was any left at this point.

Gilbert follows this up with his own sleuthing. After identifying Brittany Diamond Eugene, Gilbert arranges to meet her in person by agreeing to purchase several fashion dresses he sells. While there—and this is recorded on tape—he gets her to sign Christmas cards to people with fake names designed to be similar to words that appear in the letter that was used in the trial. One is “Blessing Turner,” to get her to sign the word “blessing,” a word that appears in the letter.

The first thing he does with this is submit it to Bart Baggett. Baggett has never been accused of indulging fringe conspiracy theories. He’s a court qualified handwriting expert in the field of forensic document examination who has testified in over 85 local and federal US court cases. After saying there’s absolutely no way Rachel Jeantel wrote it, he says he believes it’s more likely that Francine Serve wrote the cursive body of the text, although either she or Diamond Eugene could have.

The second thing he does is submit envelopes Brittany Diamond Eugene licked shut along with trash collected from Rachel Jeantel’s home as DNA samples to Speckin Forensic Laboratories in Michigan. They came back reporting a greater than 99% probability that Rachel Jeantel and Diamond Eugene are half-sisters through the Haitian mother living at Jeantel’s address, Marie Eugene. He follows up that their being half-sisters would explain why Diamond’s second phone number is listed as belonging to a “Daniel Eugene”… who it’s public knowledge is Rachel Jeantel’s brother.

Even if you don’t trust Gilbert’s reports on the results of his own sleuthing, the publicly confirm-able facts—the address on the unredacted investigative report, the fact that a Brittany Diamond Eugene lived there, the fact that the “Diamond Eugene” signatures seen on traffic incident reports and the letter given to Rachel Jeantel in the trial are exact matches—simply leave no room for doubt that his conclusion is right.

All of the unbearable cringe and strangeness of Jeantel’s testimony makes perfect sense with these pieces in place. “Don’t say my name, don’t say my fake name. Don’t say my age, don’t say my fake age.” Jeantel never went by the “nickname” Diamond Eugene—it wasn’t a nickname, it was her half-sisters actual legal name. Jeantel wasn’t 16—Diamond Eugene was. And at the end, when she says she feels “guilty” because she “didn’t know about it?” It’s clear she knows she isn’t doing a good job of answering the investigator’s questions to get them where they want to go, and she’s getting tired of seeing how frustrated they are as they keep pushing more and more questions. She actually didn’t know any details about the trial, because she was never on the phone with Trayvon that night.

In retrospect, I don’t know why we so readily accepted Rachel Jeantel as a witness in the first place. It is ironic that the camp that considers themselves to be “pro-Trayvon” want us to believe his girlfriend was someone who is obese, and barely intelligent enough to speak a sentence—even well enough to defend him in death. For my part, it seems immediately more plausible that anyone with Trayvon’s lean muscle mass and impulsive attitude would land someone more attractive and interesting than that.

It may set a low bar, but the real Brittany Diamond Eugene is certainly both of those things. I won’t summarize the emotional side of their relationship, because it’s irrelevant to the lawyer’s eye I give to cases like these. But suffice it to say that the documentary shows enough of her behavior to make me think the reason she vanished as a witness (after the initial recorded phone call with Crump, which also gave us a voice that clearly displays neither Rachel Jeantel’s bored tone or slurred incoherence) is because she was too self-absorbed to care what happened to Trayvon one way or another.