Growing Dollar Demand, Silver Weirdness

by Keith Weiner, Money Metals:

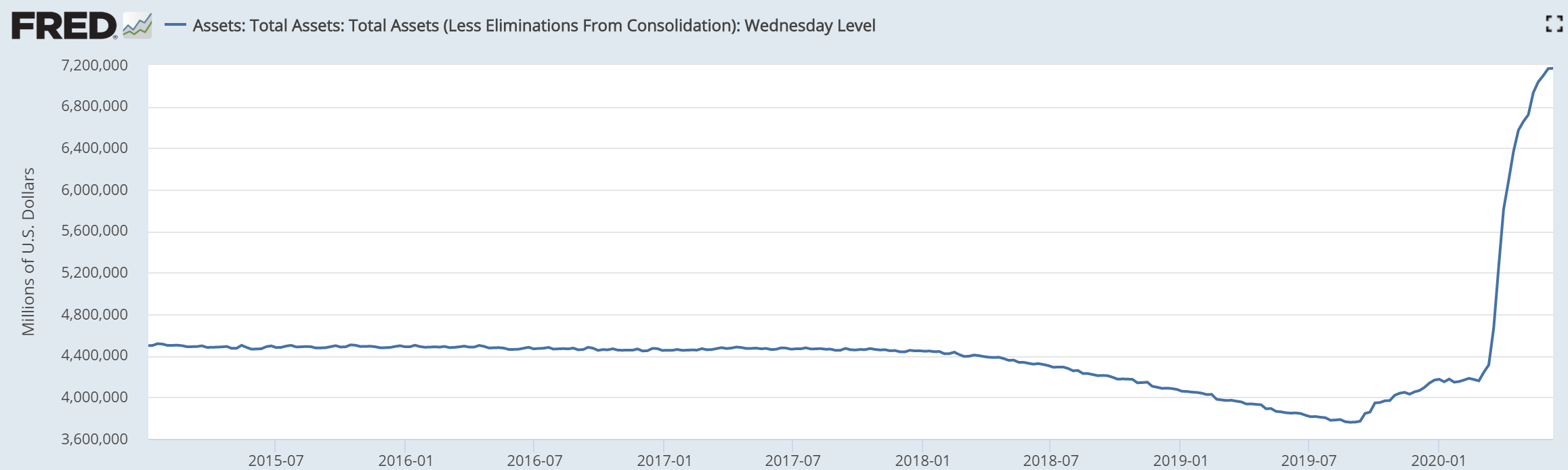

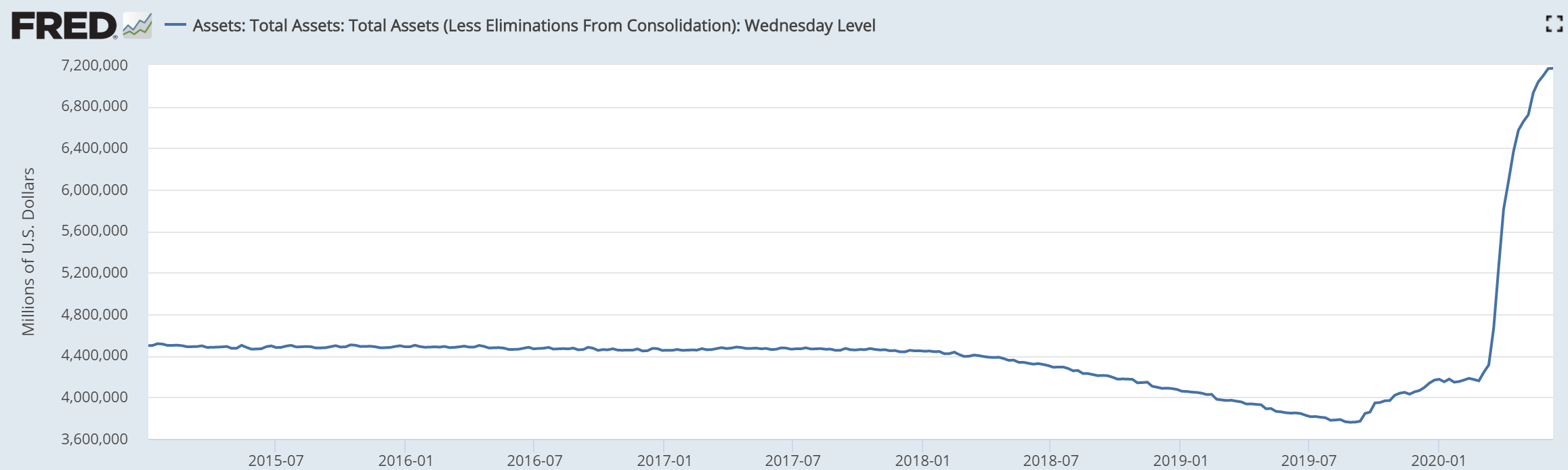

The Federal Reserve has become more aggressive again, after several years of acting docile. As you can see on this chart of the Fed’s balance sheet, it has very rapidly expanded from a baseline from (prior to) 2015 through 2018, of about $4.4 trillion. After which, it had attempted to taper, getting down to $3.8 trillion last summer. Then it was obliged to reverse itself well before responding to the COVID lockdown. Since then, its balance sheet has gone vertical.

More is expected to come. So, needless to say, more of what people call inflation—that is, rising prices—is expected to come. Never mind that in 1983, a pair of Levis 501 jeans was $50 (Keith remembers paying that price at that time) and today, the price is $35.70 at Levis.com. After 37 years of relentless—and increasingly rapid—increase in the quantity of dollars, the price of blue jeans has dropped 25%. Did we mention that crude has had not one, but two crashes in the last 6 years?

As an aside, when critics of the Fed give the impression that the main evil committed by the central bank—if not the only evil—is to cause prices to rise, and then prices do not rise, they give the impression that the Fed is doing alright. It’s not alright, as this chart shows.

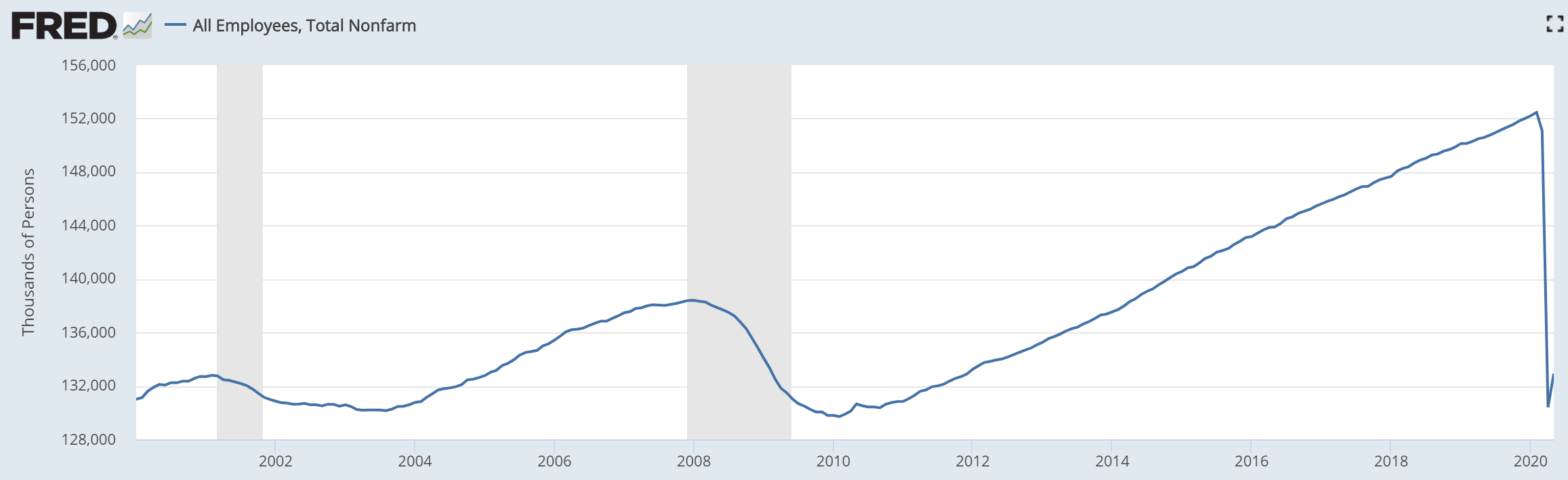

During the last debt crisis, the economy shed all of the jobs it created since the previous crisis. And now (notwithstanding there’s no grey shading yet, indicating recession) all of the jobs created since both 2009 and 2002 are gone. More will be going, when many business owners run out of money or throw in the towel. And more, when the so called Payroll Protection Plan stops subsidizing jobs for workers who are not producing enough to cover the cost of employing them.

This graph suggests that all the jobs created since 2000 were fueled by the Fed’s falling interest rates. Such jobs would be in capital-consuming industries, and not sustainable. We say this because every such job has evaporated in a time of credit crisis, in 2001, 2008, and 2020 (and we know that cutting the interest rate does juice up GDP, but activity that depends on falling rates is not sustainable.)

So today in 2020, despite a larger population and workers able to work later into their golden years (and forced to, by economic circumstances), the economy is not able to employ more workers than it did in 2000. The Fed (along with other government policies) has caused enormous discoordination. People still want to consume more, and most unemployed people want to work, but government has built a wall keeping these two groups apart.

Speaking of employment, Monetary Metals is creating value and growing—we are hiring a bookkeeper. Please contact us if interested.

It’s All About the Debt

This brings us to today’s topic. The flip side of the dollar is debt. Perhaps because people think of the dollar as money, they picture the Fed printing and skip over a Grand Canyon of faulty assumptions and unwarranted inferences to the idea that people somehow have more money to chase the same goods, and hence bid up prices. So let’s cut through this fallacy.

When the Fed creates more dollars, none of them appear in your pocket.

They do not get into the pocket of your neighbor, either. No, not even the rich guy down the street who is always driving a new Ferrari. That is not how it works.

The Fed does not gift free money to the people. It does not drop bags of cash from helicopters, notwithstanding disingenuous comments by a former Fed Chairman. It does not even give free cash to the big banks.

The Fed buys assets from them. Historically it bought Treasury bonds, but now its appetite has expanded to include mortgage bonds, corporate bonds, and municipal bonds.

To help clarify our point, let’s go through the mechanics of this. Step one, a commercial bank borrows $1 million. Step two, the bank buys a bond. That is, it gives up $1 million in cash, and gets a $1 million bond in exchange. Step three, the Fed borrows $1 million. Step four, it buys the bond. That is, it gives up $1 million in cash to the commercial bank, and gets the $1 million bond in exchange.

The act of borrowing and the act of buying are combined in one step with the Fed. It’s simple but it’s so hard to see, because people think of the dollar as money. However, the dollar is actually the Fed’s liability. When a bank sells a bond to the Fed, it prefers the Fed’s liability to the bond. If the bond is a Treasury bond, then why would the bank prefer the Fed’s credit to the Treasury’s credit?

There is not so much difference between the two. Both are government credit. The Treasury pays interest (barely) and has a maturity that is a date in the future. By law, the Fed’s credit is a current asset, that is, zero maturity. And it may be used to pay all debts.

To sell a bond is to exchange one credit paper for another.

This act does not provide free value to either party (though the Fed generally buys on an uptick in price, which is a downtick in interest rates, so there is a little capital gain). No one finds money that just appeared in his pocket. Hordes of people are not dollared-up, running out to stores to throw more dollars after the same goods.

This picture, evoked by the Quantity Theory of Money, is not a picture of reality the way Hogwarts is not a picture of a real school.