The State of the American Debt-Slaves Q2 2020: The Credit Card Phenomenon

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

Consumer debt to GDP spikes, but why did credit card balances plunge and new delinquencies decline?

Consumer debt to GDP spikes, but why did credit card balances plunge and new delinquencies decline?

OK, as I mentioned on Friday, things are a little crazy in the consumer-debt arena at the moment: No Payment, No Problem: Bizarre New World of Consumer Debt. But there is another aspect to it – that of the American debt-slaves themselves. And there are all kinds of things happening.

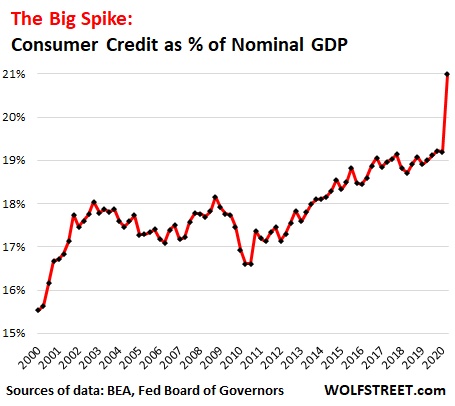

Consumer debt – student loans, auto loans, credit cards, other revolving debt and personal loans but excluding mortgages and HELOCs – declined to $4.1 trillion (not seasonally adjusted) in the second quarter, according to Federal Reserve data. It declined because credit card debt plunged – we’ll get to that phenomenon in a moment. But as the economy took a broadside in the second quarter, with 32 million people claiming unemployment insurance, consumer debt as a percent of “nominal GDP” spiked from the already record high 19.2% at the end of the Good Times in Q4 2019 and Q1 2020 to 21% at the end of the second quarter:

This ratio of consumer debt to nominal GDP shows the debt burden on consumers in terms of the overall economy. Neither consumer debt nor nominal GDP is adjusted for inflation, and the impact of inflation over the years cancels out in the ratio. So this spike in the ratio is another way of looking at the plight of consumers in this Pandemic economy.

The Credit Card Phenomenon.

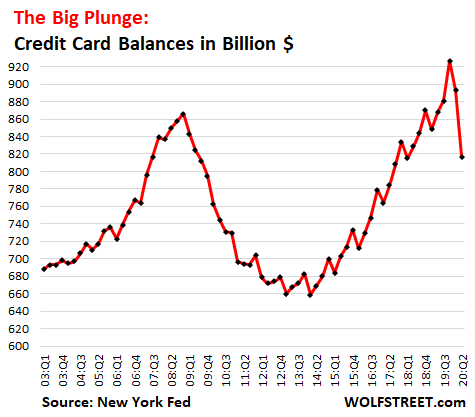

Revolving consumer credit consists of credit card debt and other revolving credit such as personal loans. Credit card debt by itself – a data set that the New York Fed provided in its Household Credit Report – fell by $82 billion in Q2, to $820 billion.

Credit card debt generally declines in the first quarter, as consumers try to get over the hangover from the holiday shopping spree. But the only times it declined in the second quarter was during and after the Great Recession when consumers were forced to seriously retrench: 2009, 2010, and 2012, and only between 1% and 2.4%. But in Q2 2020, credit card debt plunged by 9%! A decline of this magnitude has never occurred in any quarter going back to 2000:

Within Q1, the steepest declines came in April and May and persisted in June to a lesser degree.

But all other household credit categories combined – mortgages, HELOCs, auto loans, student loans, and other credit – rose nearly as much as credit card balances fell.

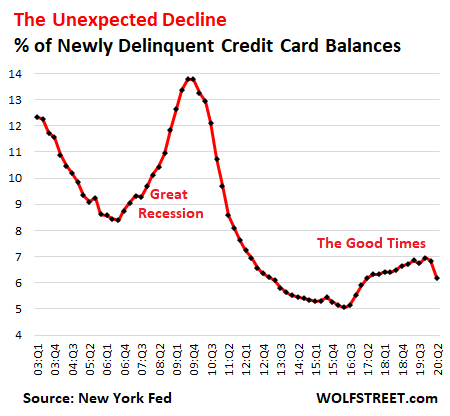

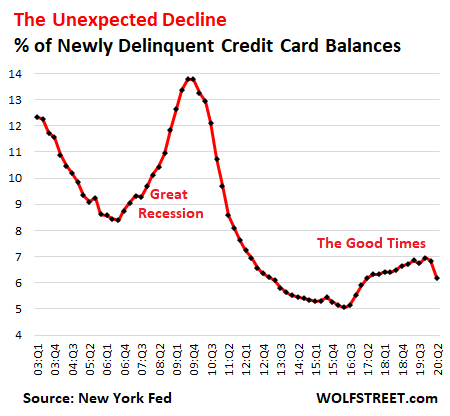

In addition, newly delinquent credit card balances fell – which is the opposite of what you’d expect them to do during an unprecedented unemployment shock.

During the Great Recession, as people who’d lost their jobs were falling behind on their credit cards, newly delinquent balances soared to approach 14%. This wasn’t just subprime, but all balances combined! Then, during and after the Great Recession, as lenders and consumers went through a painful cleansing process, newly delinquent balances declined and finally hit a two-decade low in early 2016. Then they rose again during the Good Times as the subprime segment got into trouble funding these Good Times. But in Q2 came the Pandemic economy, and suddenly newly delinquent balances dropped to 6.2%:

Why did credit card balances plunge and newly delinquent balances decline?

Nearly all consumers below a certain income level received the stimulus payments and most people who’d lost their work received regular unemployment benefits or the new federal unemployment benefits, plus $600 a week extra. Regular unemployment benefits are hard to get by on. But with the $600 a week extra, many people received more in unemployment benefits than they were making in their jobs.

“Two-thirds of UI eligible workers can receive benefits which exceed lost earnings and one-fifth can receive benefits at least double lost earnings,” according to a study by the Becker Friedman Institute for Economics at the University of Chicago.

Combine this with the numerous studies that find that about half of the households don’t have enough cash in their savings accounts for a relatively minor emergency, such as $500.