Cinema Chains Near Collapse: The Problem Beyond the Pandemic

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

Out-of-money-date for Cineworld — owner of Regal, second largest movie theater chain in the US — is in November or December, but it’s hoping for a US taxpayer bailout.

Out-of-money-date for Cineworld — owner of Regal, second largest movie theater chain in the US — is in November or December, but it’s hoping for a US taxpayer bailout.

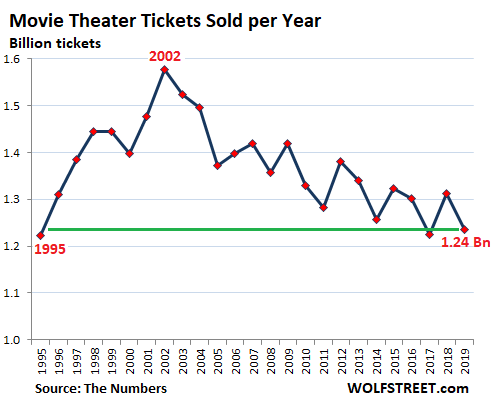

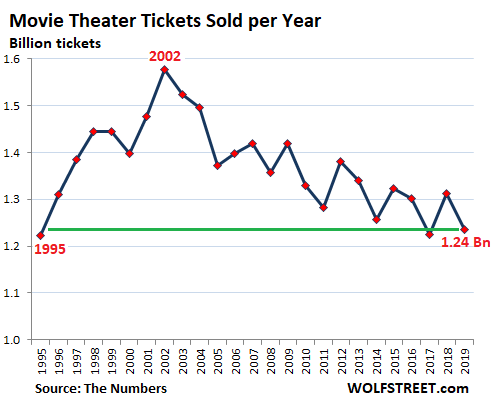

The cinema business – like brick-and-mortar malls – has been in structural decline long before the Pandemic. The number of movie tickets sold had peaked in 2002 in the US, and has since been declining, beset by competition from technologies that deliver movies to the home, at first DVDs, then Blue ray disks, and with the spread of broadband, online services, such as Netflix, Amazon, Disney, and others. People are watching more movies than ever. But they’re doing it at home: Before the Pandemic, the number of tickets sold had dropped by 22% from the peak in 2002 through 2019:

On a per-capita basis, ticket sales dropped by 31% from 2002 through 2019, from 5.5 tickets per person in 2002 to 3.8 tickets per person in 2019.

So this was a tough environment to begin with. Jacking up ticket prices while adding bars with overpriced drinks and food, and providing comfortable big chairs as amenities, worked to some extent to counteract the decline in ticket sales. In 2019, according to movie data provider The Numbers, box office sales of $11.25 billion were only a tad below 2016 ($11.26 billion) even though the number of tickets sold fell by 5%.

The Pandemic compressed the process of years into a few months.

Cineworld Group, whose Regal Theaters are the second largest theater chain in the US, behind AMC and ahead of Cinemark, announced today that it would close all its 536 Regal Theaters in the US and its 127 Cineworld and Picturehouse theaters in the UK, starting October 8, and that 45,000 jobs are at risk:

As major US. markets, mainly New York, remained closed and without guidance on reopening timing, studios have been reluctant to release their pipeline of new films. In turn, without these new releases, Cineworld cannot provide customers in both the US and the UK – the company’s primary markets – with the breadth of strong commercial films necessary for them to consider coming back to theatres against the backdrop of COVID-19.

All its cinemas closed mid-March and started to re-open in June. By August, over 70% of its cinemas were open. But blockbuster movies weren’t being released and people didn’t come.

On September 24, the UK company disclosed that in the first half, which included the pre-Pandemic period, revenues plunged 67% year-over-year, generating a net loss of $1.6 billion.

Net debt jumped to $4.02 billion (from $3.5 billion at the end of the year). This debt includes a $3.6 billion term loan whose covenants Cineworld is likely to breach in several ways – which would mean a default – unless it obtains covenant waivers.

Cineworld said it had been able to come to an agreement with its lenders to extend its $111 million revolving credit line to December 31; and that it obtained an additional loan of $250 million.

Fitch Ratings, following Cineworld’s announcement today, slashed its rating by three notches, from ‘B-’ with negative outlook, which was six notches into junk, to ‘CCC-’ which is two notches above default (my cheat sheet for bond credit ratings).

“Lower-than-expected cinema attendance across Cineworld’s operating footprint is driving a longer and deeper period of cash burn than we originally anticipated,” Fitch added.

“Fast depleting liquidity” was one of the reasons Fitch cited for the downgrade. Assuming that Cineworld’s $111-million revolving credit line is not extended again, “the company’s current liquidity levels may only be sufficient until November to December 2020.”

So the company will now have to raise new funds quickly, or else November or December will be the out-of-money date.

A US taxpayer bailout might help out. Fitch said that Cineworld, though it is a UK company, has a “high” probability of receiving $200 million in bailout funds under the CARES Act by Q2 next year, “given the tax payments of the company’s US operations in the past.”

If US taxpayers dig into their pockets to bail out Cineworld, it would “make sizable positive impact to the company’s liquidity,” Fitch said. “However, the timing does not help the company’s shorter-term liquidity needs.” Because the out-of-money-date is in November or December.

Cineworld, with lease liabilities of $4.3 billion, is among the companies that have stopped paying rent for a certain period. In its September 24 disclosure, it said that it was “successful” in getting landlords to agree to waive and defer rent payments.

Fitch, citing examples in China and Hungary, held up the possibility of a rapid “return to normality,” meaning pre-Pandemic levels of ticket sales, if the health concerns recede, and if “film releases” return to normal levels.

Film releases in turmoil, studios grapple with alternatives.

On September 3, Warner Bros. released its highly anticipated spy film “Tenet,” whose release had been delayed due to the Pandemic. But with about 70% of the theaters open in the US, and with movie goers leery of going to the movies, the $200-million movie grossed only $45 million in the US and Canada.

Movie studios reacted to avoid another fiasco like this. Warner Bros. moved the release of its “Wonder Woman 1984” from October to Christmas Day. Disney delayed the release of 10 movies by six months.

In addition – even more ominous for cinema chains – studios are starting to sell big titles directly on online platforms, bypassing cinemas altogether: This includes “Trolls World Tour” by Comcast’s Universal Pictures; and Disney’s $200-million “Mulan,” which it decided to sell on its own streaming service.

Netflix and Amazon were among the big winners in the Pandemic as consumption of goods and services – including entertainment – has shifted even more online. Movie studios, seeing the writing on the wall, have piled into it. And as brick-and-mortar malls are finding out: much of the shift to online during the Pandemic wasn’t temporary but has been staying online, and hasn’t returned to malls when they reopened.