The end of paper gold and silver markets

by Alasdair Macleod, GoldMoney:

This article looks at the likely consequences of the Bank for International Settlements’ introduction of the net stable funding requirement (NSFR) for bank balance sheets, insofar as they apply to their positions in gold, silver and other commodity markets.

This article looks at the likely consequences of the Bank for International Settlements’ introduction of the net stable funding requirement (NSFR) for bank balance sheets, insofar as they apply to their positions in gold, silver and other commodity markets.

If they are introduced as proposed, banks will face significant financing penalties for taking trading positions in derivatives. The problem is particularly important for the London gold market, as described in last week’s article on this subject. Therefore they are likely to withdraw from providing derivative liquidity and associated services.

TRUTH LIVES on at https://sgtreport.tv/

This article delves into the consequences of the NSFR leading to the end of the London forward markets in gold and silver. Replacement demand for physical metal appears bound to rise, and an assessment is therefore made of available gold not tied up in jewellery and industrial uses. An analysis of gold leasing by central banks, leading to double ownership of physical gold, is included.

The conclusion is that unless the BIS has an ulterior motive to trigger a chaotic financial reset of some sort, it is a case of regulators not understanding the market consequences of their actions.

Introduction

Last week I explained why as they stand the new Basel 3 regulations will make it uneconomic for banks to continue to run bullion trading desks.[i] The introduction of the net stable funding requirement (NSFR) means that mainland European banks, of which ten are LBMA members including the Swiss, will have to comply with the new regulations from the end of June, and all UK banks, in effect the entire banking membership of the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) will have to comply by the year-end. There are 43 LBMA members listed as banks, and on Comex there are currently 17 with long and 27 with short positions in the Swaps category, which represent bullion bank trading desks in the dominant futures contracts. So being similar, the Comex numbers must broadly replicate those operating in London. It is therefore reasonable to assume that if the LBMA’s banking membership ceases dealings in unallocated bullion, then very few will continue to deal on Comex — the LBMA crowd having ceased taking trading positions.

We are discussing not gold or silver but their derivatives. But there is a problem borne out of the LBMA’s insistence that it involves bullion, albeit unallocated, and not derivatives. The distinction could be important, depending on how the UK regulator applies the NSFR rules. This is because in the calculation of required stable funding, gold consumes 85% of available stable funding while gold liabilities contribute no available stable funding at all. The effect is to impart a negative factor into a bank’s overall net stable funding calculation, making unallocated gold trading hopelessly uneconomic in terms of deployment of total funding capital. The alternative, which does not appear to be under the LBMA’s consideration, is to admit that the whole unallocated gold trading business has nothing to do with gold bullion but is in fact gold derivatives; in which case capital funding penalties under the NSFR would be broadly limited to imbalances between derivative liabilities and derivative assets.

Consequently, it appears that an allocation backstop of 85% of available stable funding (ASF) must be swallowed in the case of gold, which does not appear to be the case if the LBMA confesses to the paper charade.[ii]

There are in London, in effect, two markets conflated into one, but they must not be confused. The unallocated market, otherwise known as dealing for forward settlement, is the product of bank credit expansion, not as the LBMA claims, physical metal whose bar origins, weights and fineness are not recorded for convenience’s sake. Perhaps the LBMA would like to let us know where they think it’s all stored; it’s certainly not in LBMA vaults, where after deducting headline figures for custodial gold the float reduces to as little as a few hundred tonnes. Unsurprisingly, the Bank for International Settlements lists these transactions as over-the-counter derivatives for statistical purposes, so we know how they are regarded by the international regulator.

Physical gold held on behalf of customers is never recorded on bank balance sheets. If a bank owns physical gold in its own vault, an independent vault, or allocated to it by another bank acting as custodian with its own vaulting facilities then that appears as an asset on its balance sheet. In that case, it can hedge out the price risk with a matching liability for a zero price-haircut within Basel 3 rules. But this has nothing to do with the NSFR calculation.

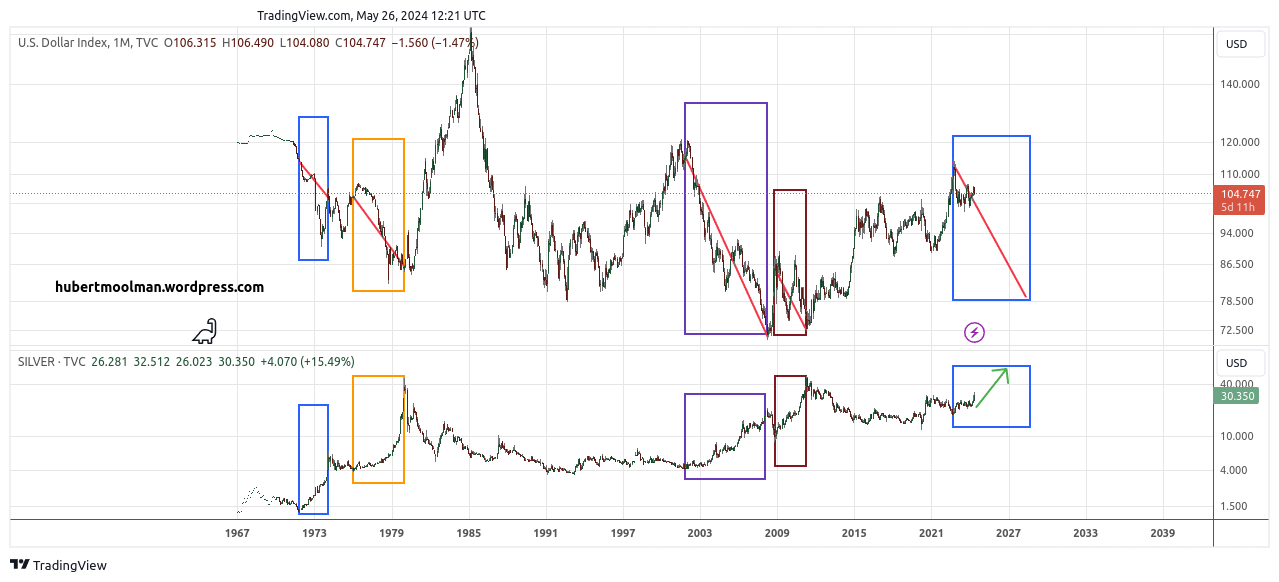

Clearly, unless the NSFR calculation is amended at the last moment, following its introduction the character of bullion markets will become markedly different. Gone will be roughly $600bn of paper gold[iii], while presumably some of the paper demand released will migrate to physical metal. There is also the question of how outstanding imbalances will be resolved. This article assesses the consequences.

Unknown motives and politics

It is difficult to understand why the Financial Stability Board, under whose aegis the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has produced Basel 3, seems intent on destroying derivative markets for gold, silver and also for other commodities. That will be the consequence of the introduction of the NSFR calculation in these markets. As the supreme authority overseeing fiat currencies, the Bank for International Settlements, which oversees the FSB, has no love for gold. One can explain the desire to do away with it: as the riskless form of money, it has been at the centre of monetary affairs for ever and the desire to do away with it must be overwhelming for neo-Keynesian modernists. But if that is the case, then it will be a serious misjudgement, because as this article reveals, the consequence of withdrawing paper supply is likely to drive the gold price significantly higher, along with silver and a host of other important commodity prices. Furthermore, this delayed act, first published in 2014, now comes at a time of rapidly rising commodity prices, reflecting the unprecedented acceleration of global money-printing in 2020, which ironically proves the importance of sound money — gold.

Already, tight, gold silver and commodity markets cannot accommodate a migration out of defunct paper into physical metals and energy without massive price rises to defuse the unsatisfied demand unleashed by this action. Perhaps the regulators at the FSB know this. If they do, then we can only conclude it is a deliberate attempt at a reset of all commodity markets. Bank corruption, particularly in precious metals has been rife: major banks have been regularly fined and continue to manipulate and spoof these markets, fines being seen as little more than a cost of doing business. These are systemic risks a regulator should address. But to assume the FSB is shutting down these paper markets to curb this behaviour exhibits a touching faith in its altruism.