Dawson City: Frozen Time

Dawson City: Frozen Time is an extraordinary documentary about the 1978 Dawson Film Find, the unlikely tale of when hundreds of hitherto missing and presumed lost silent films and newsreels were rediscovered buried under a swimming pool in Dawson City, a microscopic town of 1,375 people in the Canadian Yukon, 150 miles south of the Arctic Circle. You can watch it here.

Dawson City: Frozen Time is directed by Bill Morrison, who makes films incorporating images from silent films combined with contemporary mood music.

Not all of these are documentaries. Morrison sometimes makes more avant-garde movies which give one the impression that they are intended to be watched while high (example here). His critically-acclaimed 2002 film Decasia was an hour-long visual acid trip composed entirely of silent film clips in various states of decay.

Dawson City: Frozen Time is not just about the Dawson Film Find, but tells the history of Dawson City and nitrate film as well. Understanding both are necessary to appreciate the real significance of the event. There is no narration; the story is told with words written across the screen. The only spoken words you hear are from interviews in the first and last few minutes of the film. Other than that, this documentary about silent film is a silent film itself.

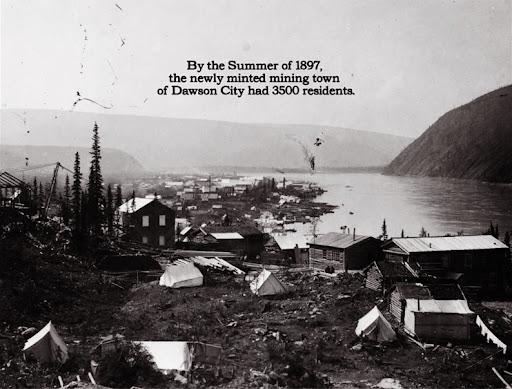

Dawson City is a place that human history chewed up and spit out. It exists today as a shadow of its former self, a town that time forgot. But for 12 months during 1897 and 1898, it was the epicenter of the Klondike gold rush and swimming in wealth. After the discovery of gold in Rabbit Creek, about 100,000 stampeders attempted the long and remorseless journey across the frozen Canadian tundra to Dawson City. Only about 30,000 arrived successfully, the rest either died en route or gave up, turned around, and returned home. At its peak, Dawson City had a population of 40,000.

The Yukon gold rush proved to be short lived. After gold was discovered in nearby Alaska, most of the latecomers who had arrived in Dawson after all the land had already been claimed moved on. Advances in mining technology had also reduced the need for labor. After a couple of decades, Dawson City’s population fell to around 1,000.

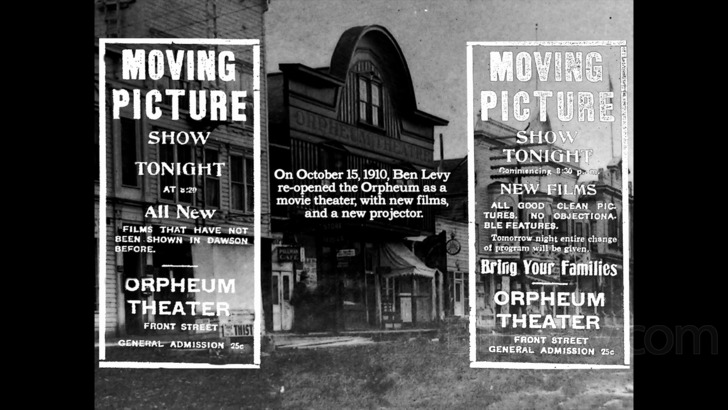

The town was nevertheless big enough to support three cinemas, as film was especially important for its residents. To say that Dawson City is in the middle of nowhere would be a gross understatement. The nearest signs of civilization were light years away. Movies were the Dawsonians’ only window into the rest of the world.

The way film distribution worked in those days was that a film would be sent to one town and shown there for a period until it was sent off to another, and so on. Dawson City was the final stop on the distribution line, and it would usually take two or three years after a film was released for it to get there.

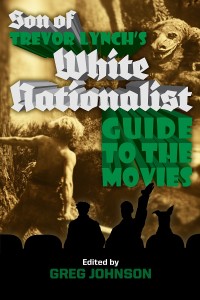

You can buy Son of Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here

Once the films had been run in Dawson, distributers often refused to pay to have them shipped back. By then, the movies were three years old; the actors and fashions may have gone out of style, advances in filmmaking cause them to look clunky compared to more recent ones, and so on. As a result, Dawson City ended up with huge stockpiles of films that no one wanted and which were technically the property of the film distributers.

Additionally, nitrate film was extremely flammable and was known to spontaneously combust. Dawson City: Frozen Time tells quite a few horror stories of occasions when nitrate film factories exploded or when cinemas caught on fire, killing scores of moviegoers. Nitrate film is in fact so flammable that it will continue burning even if it is submerged in water. While it can be enraging to hear about people destroying art, one can have some sympathy in this instance knowing that trying to preserve these films would have essentially meant holding on to ticking time-bombs.

As a result, most of the films they received were either thrown into the nearby river (how Dawson City had historically disposed of its garbage), or were otherwise destroyed at the beginning of the sound era. Once talking pictures began coming to Dawson City in the early 1930s, it was assumed that silent films were obsolete and that no one would be interested in them again. Dawson City wasn’t alone in this: 75% of all silent films that were produced are now considered lost, as they were disposed of everywhere for the same reasons. Many silent film archives were also lost in fires, as all it takes is an electrical spark or the air conditioning going out on a hot day to start one when it comes to nitrate film.

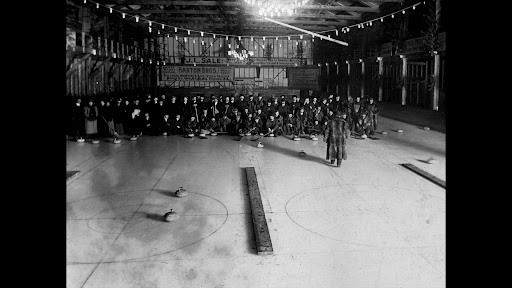

What made Dawson City unique in this respect was that it had an athletics facility with a swimming pool. The pool was converted into a skating rink in the winters. There was a problem with it, however, in that the due to a construction error, the skating rink’s surface was always uneven. Someone finally had the bright idea to fix it by using some of the old cans of film as landfill underneath the pool’s bottom. It worked. The rink was now even and the films were forgotten.

Ironically, while nitrate films elsewhere were being destroyed in fires, this was not the case in Dawson City. Underground, the films were protected by a layer of permafrost. They were so well-protected, in fact, that they survived even after the athletics facility they were buried under burned to the ground.

It was not until 1978, when construction workers were preparing to erect a new building on the grounds of the former athletics facility, that the film cans were rediscovered. Most of them had some water damage. Some were in pristine condition.

Perhaps even more importantly, newsreels were also recovered. Some of them included priceless footage of historical events like the First World War, labor strikes, and the 1917 and 1919 World Series.

Compared to Morrison’s other work, Dawson City: Frozen Time is a relatively straightforward documentary, although still quite artsy-fartsy (but in a good way). What makes it stand out is its atmosphere, mood, and the immersive quality created by Morrison’s masterful interplay between the visuals and ambient, Brian Eno-esque music.

At the risk of sounding pretentious, Dawson City: Frozen Time is more than a documentary — it’s an experience. I feel silly saying that, but I’ll be damned if it isn’t true.

* * *

Counter-Currents has extended special privileges to those who donate $120 or more per year.

- First, donor comments will appear immediately instead of waiting in a moderation queue. (People who abuse this privilege will lose it.)

- Second, donors will have immediate access to all Counter-Currents posts. Non-donors will find that one post a day, five posts a week will be behind a “paywall” and will be available to the general public after 30 days.

To get full access to all content behind the paywall, sign up here: