Theodor Herzl and Pope Pius X, by Salim Mansur

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

—Søren Kierkegaard (1813-55)

i]

In the “George Macaulay Trevelyan Lectures” delivered January-March 1961 in the University of Cambridge, Professor E.H. Carr (1892-1982) set out to discuss the proposition “what is history”. The lectures were subsequently published, as a small book What is History?, in the same year the lectures were given, and since then it has been a popular text for lay readers and students of history. The proposition that animated Carr was relatively recent in origin, since from the earliest record-keepers until a few generations before him those in Britain, engaged in keeping records for posterity of activities of movers and shakers of their respective societies and civilizations, they had remained unaware, or uninterested, about methodological and philosophical questions related to their practice.

By the time Professor Carr was invited to give the Trevelyan Lectures, the proposition was no longer about record-keeping, about merits of the records kept and reported in terms of their reliability as ascertainable facts or myths and legends, or what such records tell us about the past, but how they might illuminate the present in the effort to understand the predicaments of our own time. History as a discipline slowly matured with the progress in human thought from timeline record-keeping of human journey from the earliest dim beginnings of society into making of the modern age of science and technology. Carr’s lectures were given well past the mid-point of the twentieth century in which his generation had lived through two world wars, the Bolshevik revolution that he wrote about in multiple volumes, the Holocaust and the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the beginning of the end of the age of European colonialism-imperialism with its ancillary of colonial-settler states in Africa (South Africa and Rhodesia) and, as it seems increasingly likely, in western Asia (Israel). Carr wrote,

Professor Butterfield as late as 1931 noted with apparent satisfaction that ‘historians have reflected little upon the nature of things, and even the nature of their own subject.’ But my predecessor in these lectures, Dr A.L. Rowse, more justly critical, wrote of Sir Winston Churchill’s World Crisis – his book about the First World War – that, while it matched Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution in personality, vividness, and vitality, it was inferior in one respect: it had ‘no philosophy of history behind it.’ British historians refused to be drawn, not because they believed that history had no meaning, but because they believed that its meaning was implicit and self-evident. The liberal nineteenth-century view of history had a close affinity with the economic doctrine of laissez-faire – also the product of a serene and self-confident outlook on the world. Let everyone get on with his particular job, and the hidden hand would take care of the universal harmony. The facts of history were themselves a demonstration of the supreme fact of a beneficent and apparently infinite progress towards higher things. This was the age of innocence, and historians walked in the Garden of Eden, without a scrap of philosophy to cover them, naked and unashamed before the god of history. Since then, we have known Sin and experienced a Fall; and those historians who today pretend to dispense with a philosophy of history are merely trying, vainly and self-consciously, like members of a nudist colony, to recreate the Garden of Eden in their garden suburb. Today the awkward question can no longer be evaded.

Professor Carr cited the German historian Leopold von Ranke writing in the 1830s that the task of the historian was “simply to show how it really was”. A century later Carr cited the British historian Geoffrey Barraclough writing, “The history we read, though based on facts, is, strictly speaking, not factual at all, but a series of accepted judgements.” It was with Benedetto Croce, according to Carr, that in the new century, the twentieth, “the torch passed to Italy, where Croce began to propound a philosophy of history which obviously owed much to German masters. All history is ‘contemporary history’, declared Croce, meaning that history consists essentially in seeing the past through the eyes of the present and in the light of its problems, and that the main work of the historian is not to record, but to evaluate; for, if he does not evaluate, how can he know what is worth recording?” (italics added).

In the second half of the twentieth century advancements in behavioural sciences, such as studies in cultural and political anthropology, political economy, psychology, sociology, including the hermeneutics of literary criticism, and developments in jurisprudence with evolution in international law and adoption of declarations, treaties and conventions on human rights and on war crimes under the umbrella of the United Nations and its Charter, enriched historiography in terms of contextualizing and evaluating events on criteria that should rest ultimately on a moral foundation based on universal values of individual freedom and equality. History and historical writing were slowly democratized, as voices that previously went unheard, or were marginalized, entered the stage and brought with them their stories, their experiences, and their claims for recognition as active agents in history.

The democratization of historiography means that history becomes an arena of contest between competing voices and interests, the increasing presence of those whom Frantz Fanon called the “wretched of the earth,” – the people of the Global South emancipated from the yoke of European imperialism and colonialism – and recognizing with Carr that the world in terms of human affairs is perpetually in motion. This is how Professor Carr concluded his “Trevelyan Lectures”, as transcribed in his book:

At a moment when the world is changing its shape more rapidly and more radically than at any time in the last 400 years, this seems to me a singular blindness, which gives ground for apprehension not that the world-wide movement will be stayed, but that this country – and perhaps other English-speaking countries – may lag behind the general advance, and relapse helplessly and uncomplainingly into some nostalgic backwater. For myself, I remain an optimist; and when Sir Lewis Namier warns me to eschew programmes and ideals, and Professor Oakeshott tells me that we are going nowhere in particular and that all that matters is to see that nobody rocks the boat, and Professor Popper wants to keep that dear old T-model on the road by dint of a little piecemeal engineering, and Professor Trevor-Roper knocks screaming radicals on the nose, and Professor Morison pleads for history written in a sane conservative spirit, I shall look out on a world in tumult and a world in travail, and shall answer in the well-worn words of a great scientist: ‘And yet – it moves.’

The world is in motion, it does not cease to move, and the rhythm of that movement is marked in the beat of its progress and decay. It is said philosophy begins in wonder when man on becoming aware of the world around him and his place in it asks questions and seeks answers. It is when record-keepers and story-tellers begin wondering about the nature of their work that the first steps are taken to go beyond record-keeping and story-telling in search for meaning in their work, of situating the particular recorded story within some larger framework of end purpose, teleology, that may be religious or secular. This search for “meaning” in history presupposes some standard, such as the concept of an “age” or “era” defined by some criterion such as the bronze age or the Roman era, by which the “meaning” of events and personalities studied is assessed, evaluated, and judged.

The question, “what is history?”, evolves from is into becoming, as the German poet Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) intuited, the “history of the world is the world’s court of justice”, and to the unending unease of partisans their cause/ideology (for instance, Zionism) and its leading personality (for instance, Theodor Herzl) are subjected to scrutiny and brought to judgment. And this is also why there is an unending war against historians by those disaffected by such scrutiny and judgment who seek to censor or silence them, as Zionists and their supporters have been engaged in censoring and/or silencing new or revisionist historians of Zionism and Israel.

ii]

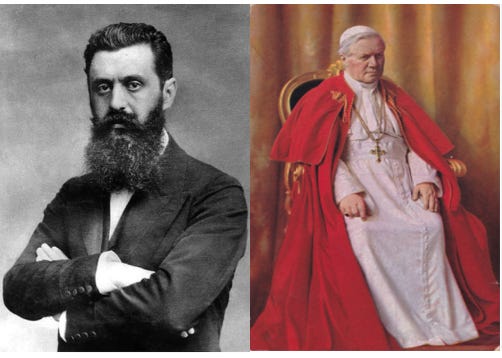

On January 26, 1904, Theodor Herzl, writer, journalist, political activist, and founder of the nascent world Zionist organization at the first Zionist congress held in Basel, Switzerland, on August 29-31, 1897, walked into the Vatican, Rome, for an audience with Pope Pius X. Herzl was forty-three years old, and in the previous eight years he had risen from relative anonymity in Vienna into a blazing comet in the firmament of European Jewry. Five months after meeting with the Pope, Herzl died on July 3 at a sanatorium in Edlach, outside of Vienna, of cardiac sclerosis.

Herzl was born to Jeannette and Jakob Herzl, their second child, in Budapest on May 2, 1860. Jakob was a banker and a successful businessman. Jeannette née Diamant was raised by wealthy Budapest Jewish parents, and together Jeannette and Jakob made a happy home for Herzl and his sister Pauline, a year older than him. The Herzls were assimilated Jews in the Austro-Hungarian empire, and fondly leaned towards Germany as the source of their cultural enrichment. The family moved to Vienna in 1878 following the death of Pauline with typhoid fever. It was a move dictated by Jeannette’s grief and the wish no longer to reside in the house and city where she had raised Pauline and lost her. For Herzl the move to Vienna was a grand entrance into the most cosmopolitan and culturally vibrant city of the empire, and in the fall of 1878 he enrolled as a student in the Faculty of Law at the University of Vienna.

In mid-nineteenth century following the end of the Napoleonic wars Europe was jolted by the revolutions of 1848-49 that came to be known as the “springtime of peoples and nations.” The liberal ideas of the French revolution were taking hold of people in central Europe, as they sought emancipation from authoritarian controls of old regimes. It was also the time when “secularization” of politics and society, of separation of church and state, heralded by the French revolution began to seize the minds of the general populace beyond France and generate new problems that accompanied it. Owen Chadwick, the English historian of the period, observed “the problem of secularization is not the same as the problem of enlightenment. Enlightenment was of the few. Secularization is of the many.”

Enlightenment had meant the emancipation of the individual from the group think and the reigning prejudice in society that could not be defended by reason. It further meant a society was not a free society where freedom reigned unless the individual was free and his freedom was protected. “The liberal mind (in this sense),” Chadwick wrote, “was individualist. It looked upon the solitary conscience in its right to be respected.” The liberal theory in this earlier phase was negative, to free the individual from the clutter of the old and the hold of the past that constrained and coerced him. But secularization as emancipation in the next phase would come to mean peoples and nations striving for freedom to live as sovereign people according to their inherited values of religion and culture in a territory of their own.

It was in the midst of such immense social change that Herzl came of age and entered university in a city when that moment in its history seemed to represent for European Jews the ideal of emancipation for individuals and for a people. Stefan Zweig, a writer, poet and dramatist, was born in Vienna in 1881 to a bourgeois Jewish family of Moravian origin. In his autobiography The World of Yesterday, Zweig described the city of his birth that became Herzl’s home and its splendour in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century, as follows:

There is hardly a city in Europe where the drive towards cultural ideals was as passionate as it was in Vienna… The Romans had laid the first stones of this city, as a castrum, a fortress, an advance outpost to protect Latin civilization against the barbarians; and more than a thousand years later the attack of the Ottomans against the West shattered against these walls. Here rode the Nibelungs, here the immortal Pleiades of music shone out over the world. Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, and Johann Strauss, here all the streams of European culture converged. At court, among the nobility, and among the people, the German was related in blood to the Slavic, the Hungarian, the Spanish, the Italian, the French, the Flemish; and it was the particular genius of this city of music that dissolved all the contrasts harmoniously into a new and unique thing, the Austrian, the Viennese. Hospitable and endowed with a particular talent for receptivity, the city drew the most diverse forces to it, loosened, propitiated, and pacified them. It was sweet to live here, in this atmosphere of spiritual conciliation, and subconsciously every citizen became supernatural, cosmopolitan, a citizen of the world.

Herzl’s home was dominated by his mother Jeannette. Her family had migrated from Moravia and Slovakia to Hungary in the eighteenth century, and her father became wealthy in the clothing business in Budapest. Jeannette’s admiration for German Kultur was reflected in her love for German poetry and this love along with her favourite poets – Goethe, Schiller, Heine, Lenau – were passed on to Herzl. He was hardly instructed in Judaism and showed no interest in religion growing up in Budapest and Vienna. According to Amos Elon, Herzl’s biographer and the best-selling author of The Israelis: Founders and Sons, “The future Zionist leader grew up as a thoroughly emancipated, antitraditional, secular, would-be German boy.”

Later in life Herzl tended to romanticize his family’s origin. He spoke of his descent from the noble Spanish Marraños, whereas the Herzl family could barely trace its origin to the early eighteenth century. Amos Elon explained this tendency as self-delusion of recently emancipated Jews from their ghettos and “on the prevailing snobberies of the age.” Elon wrote,

In the nineteenth century many assimilated Western Jews professed a Sephardic origin. The romantic poets, in particular Byron and Heine, had attached an aura of marvelous nobility to the proud Jews of medieval Spain. Moreover, at a time when the rich, liberated Jews of the West sought to dissociate themselves from their poor and outcast coreligionists in Poland and Russia, only a Sephardic origin was conclusive proof that one did not come from the primitive Ostjuden (Eastern Jews)…

The romantic mind requires that power or success or fame be somehow legitimized by heritage. Herzl’s father’s family was in fact Ashkanazi, not Sephardi. It came not from Spain but from Silesia, Bohemia, and Moravia. The name Herzl is a German translation of the Hebrew lev (heart).

The decade of the 1880s and the early years of 1890s were the seminal years for Herzl’s development as a writer and dramatist. These were the years when he was just about entirely dependent on his parents, his doting mother Jeannette for her only son and remaining off-spring and the generosity of his father Jakob. His reluctant effort as a law clerk at the Vienna District Court filling out legal forms depressed and bored him, his apprentice journalism and writings were yet to be recognized and, Elon wrote, in his mid-twenties he “grew a beard, perhaps as a concession to an age when youth was a hindrance to all careers…The beard suited Herzl’s delicate, slightly hooked nose and high forehead, and seemed to soften his deep voice. He still led a solitary life.”

But these were the years when Europe as a continent reached its apogee as the centre of the world in arts and culture, in high-finance, industry, and military power. Europe’s population at the beginning of the century was under 200 million, and as the decade of 1890s drew to an end the population doubled. The Jewish share of the population grew from an estimated 1.6 per cent during the first half of the century to 2.2 per cent at the end amounting to an estimated 8.7 million European Jews.

https://www.iijg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Leit...ed.pdf The doubling of Europe’s population was accompanied by the growth in urbanization, the internal migration of people unloosed from working the land to newly expanding towns and cities for employment as skilled craftsmen and factory-workers. It was also the high noon of European colonialism-imperialism when the great scramble for Africa reached its peak. The Berlin Conference of 1884 was convened at the instigation of Belgium and Germany to carve up what remained of the continent of Africa after Britain and France had already staked their claims, and parcel off the pieces among those European powers as latecomers to the spoil. Across the Atlantic, with the civil war ended, the continental United States was animated to rise as a phoenix from its own ashes as a great power in its own right.

The world was on the move as it has always been, but the movement had gathered a momentum by the middle of the nineteenth century that was new and unprecedented in bringing about change for which people were unprepared. The century had opened seized by radically new ideas of nation and nationalism given force by the French revolution of 1789, these being entirely European ideas transmuted into a doctrine that would tear the continent apart and impact rest of the world in ways that their theorists and dreamers never imagined. Change precipitated dislocation in the lives of people. The dark underside of change in Europe wrought by ideas, as Owen Chadwick explained, began with the conflict between enlightenment and secularization, between the “few” liberated from past prejudices and unexamined ideas, and the “many” dislocated from their customs and traditions by the forces of industrialization, urbanization, and the newest idea of nationalism as a political remedy for mitigating past conflicts. One of the conflicts that got sharpened and spilled over into the cities from the countryside was the old bigotry of Europe’s Christian majority population against its minorities, especially the Jews.

In an enlightened Europe bigotry against Jews on the basis of religion could only be an anomaly. The deep old currents of religious sectarianism and wars of reformation and counter-reformation among Christians of Europe from the 15th-16th centuries had receded and were replaced by revolutionary ideas of “individual freedom” and the “rights of man” seeded in the 17th-18th centuries. The French revolution embodied the ideals of the “age of enlightenment” in sweeping away the legacies of ancien regime based on monarchy and aristocracy over the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The new social bond among people as nation would be that of citizenship. And so the Jews of France, as Simon Schama narrates in his “story of the Jews”, appealed to the new revolutionary National Assembly meeting in Versailles following the revolution of July 14, 1789:

On August 26, the last day of debate, a deputation from the 500-odd Jews living in Paris – some of whom were personally known to the Assembly – set out with forthright clarity exactly what it was they expected and hoped for: ‘We ask that we be subject like all Frenchmen to the same laws; the same police; the same courts; we therefore renounce for the public good and in our own interests, and always subject to the general good, the rights we have always been given to choose our own leaders.’ It was a moment of breathtaking optimism and courage. The Paris Jews were declaring that they were prepared to leave behind all the familiar protections and restrictions of their ancient self-governance for the new abstract world of citizenship.

It was Stanislas de Clermont-Tonnerre, member of the National Assembly, addressing the chamber a few months later with the debate on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen nearing an end, who offered his famous formulation for the emancipation of Jews as citizens of France. Clermont-Tonnerre said, as Schama continues,

‘Jews should be denied everything as a nation; granted everything as individuals; it is claimed that they do not want to be citizens… [but] every individual wants to become a citizen. If they do not want this then they must inform us and we shall be compelled to expel them… [for] the existence of a nation within a nation is unacceptable to our patrie.’

For a moment, at the word ‘expel’, the cordial handshake of fraternity remade itself into a fist. But it relaxed once more, as Clermont-Tonnerre dismissed his own rhetorical reservation. There was, he said, no sign whatsoever of the civic churlishness their critics attributed to them or any shrinking back from the extended hand of fraternity. In the absence of any such signs to the contrary, he went on, ‘the Jews must be assumed to be citizens … as long as they do not actively refuse to be so, the law must recognise what mere prejudice rejects’.

The motion was made and lost by a vote of 408 to 403. It would take several more months of discussions within the Assembly and the need to patch divisions among Jews between those belonging to the Sephardi community and those to the Ashkenazi, before a final vote on September 28, 1791, ahead of the closure to the debate on the constitution, that citizenship was finally extended to all French Jews. The debate and the votes showed the inherent conflict between enlightenment and secularization, that a principle based on reason for adoption was easily grasped by the few, but it needed time for the many to be persuaded and even more so for the majority of people to accept and adopt as the norm by which to live.

The ideals of enlightenment and the ideas of the French revolution percolated through the few to the many in the western half of Europe before the 1848-49 revolutions in central Europe culminated with the unification of Germany under Prussian rulers, and the risorgimento (“rising again”) of Italian patriots in the making of a unified Kingdom of Italy. But east of Germany in Poland, the Baltics, and the Russian empire of the Czars emancipation was retarded by reaction of the rulers. Germany was the hinge state between emancipation and reaction in Europe, and the more discerning Jews of eastern Europe found themselves imprisoned within the boundaries of Poland and Russia, including the Baltics, known as the Pale of Settlement under Russian rule.

The distribution of Jews within Europe was lop-sided with an estimated 85 per cent of the total, or 7.4 million of the 8.7 million Jews, residing in the east. Jews lived scattered in small towns and villages across the Pale among the gentiles or the majority Christian populations, and maintained an autonomy in these small towns, in Yiddish, shtetl, meaning “mini-city.” According to Heinrich Graetz (1817-91) in History of the Jews, “The general, political and economic conditions of Poland led the Jews to live as a state within the state, with their own religious, administrative and financial institutions. The Jews formed a special class there, enjoying a special internal autonomy.” The estimated 7 million Ashkenazi Jews of eastern Europe were the progeny of the Khazars, a Turkish offshoot, that settled in the region north of the Caucasus in the sixth century, or thereabouts, established a kingdom in the mid-eighth century and the Khazar king, his ruling court, and the military class converted to the Jewish faith and Judaism became the state religion of the Khazars. Arthur Koestler in The Thirteenth Tribe described what followed:

What is in dispute is the fate of the Jewish Khazars after the destruction of their empire, in the twelfth or thirteenth century. On this problem the sources are scant, but various late medieval Khazar settlements are mentioned in the Crimea, in the Ukraine, in Hungary, Poland and Lithuania. The general picture that emerges from these fragmentary pieces of information is that of a migration of Khazar tribes and communities into those regions of Eastern Europe – mainly Russia and Poland – where, at the dawn of the Modern Age, the greatest concentrations of Jews were found. This has led several historians to conjecture that a substantial part and perhaps the majority of eastern Jews – and hence of world Jewry – might be of Khazar, and not of Semitic Origin (emphasis added).

The irony of the Khazar origin of east European Jews would get masked in the term “anti-Semitism” first employed by Wilhelm Marr (1819-1904), a German journalist, in his pamphlet The Victory of Judaism over Germanism published in 1873, as a racial opprobrium against Jews. Marr was a baptized son of a Jewish actor and of his four marriages one was with a Jewish woman and another with a woman raised in a Christian-Jewish household and, according to Moshe Zimmermann, – an Israeli historian and Marr’s biographer, Wilhelm Marr: The Patriarch of Anti-Semitism (1986) – Marr late in life renounced anti-Semitism and asserted he had originally been a “philo-Semite.” Christians have not been anti-Semites, since Christians of Palestine and the Arab-Islamic world are Semites, instead they have been anti-Jew based on the New Testament history of Jewish animus towards Jesus that culminated in his crucifixion. Marr’s terminology twisted religion-based anti-Jew sentiments of Christians – Catholics and Protestants – into race-based animus at a time in European history when the winds of enlightenment had begun to dissolve religious prejudices through the higher criticisms of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. But Marr’s race-based terminology of anti-Semitism nicely fit into the pseudo-science of race theories, which emerged following the growing popularity with Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution based on natural selection in his book On the Origin of Species first published in 1859.

iii]

While Europe was on the move, Herzl was wrestling with his own inner torments of finding a place for himself in the Viennese society of the 1880s. Anti-Semitism to the extent it was noiticeable was then merely an annoyance. It was not, Elon wrote, “something that affected Herzl’s own life, which remained sheltered, or his career as a German artist. He did not identify with the Jews, as a people or as a faith.” More than half-century removed from Herzl’s Vienna, Jean-Paul Sartre described anti-Semitism laconically as “a poor man’s snobbery.”

Herzl’s personal life turned out unhappy. He met in 1886 Julie Naschauer, an eighteen year old blond, blue-eyed, attractive daughter of a millionaire businessman and industrialist in drilling and drainage machinery, and both together fell in love. They married in 1889 and shortly thereafter discovered their marriage was a mismatch. Julie and Herzl had three children together, two daughters Pauline and Trude and in the middle a son, Hans. Herzl wanted a divorce, but to spare the children the bitterness and pain settled for a separation. In the meantime, Herzl began contributing to the Neue Freie Presse of Vienna while travelling in Italy and Germany. In the midst of his travels he was offered the position of Paris correspondent for the paper at a thousand francs a month and eighty francs for each article published. Herzl accepted the offer and headed to Paris immediately in 1891.

In Paris Herzl learned of developments in Vienna surrounding the emergence in 1893 of Karl Lueger and his Austrian Christian Social Party. Lueger’s party was populist and anti-Semitic, and in its platform was the call for repealing emancipation and eventually expelling Jews from the empire. In 1894 the Dreyfus affair came to light in Paris and for the next twelve years into the new century it moved and shook France tearing away at her republican roots. This was the story that turned into a raging scandal when Captain Alfred Dreyfus, an artillery officer in the French army assigned to the General Staff, was suspected of espionage, indicted and tried on circumstantial evidence, found guilty, sentenced for life and ordered confined to Devil’s Island – one of the three prison islands – off the coast of South America for hardened criminals. Dreyfus was also a Jew and to the end he had maintained his innocence.

Herzl as the Paris correspondent of the Neue Freie Presse covered the Dreyfus trial. It was the trial of the century in France and not merely of a military officer accused of spying for the third republic’s most damned enemy, Germany, but also of France as both daughter of the Catholic Church and daughter of the great republican revolution of 1789. It brought out the worst and the best of France. It riveted the eyes of all Europe on Paris in the final years of the nineteenth century where passions generated over the guilt or innocence of a Jewish officer serving in the once Grande Armée of Napoleon, of its famed battles of Marengo, Austerlitz, Wagram, of Goethe witnessing the Army of Valmy in 1792 reportedly exclaiming, “From this day forth commences a new era in the world’s history,” spilled over from the right and the left turning the trial of Dreyfus to become in effect the trial of France in the eyes of all Europe transfixed with the question whether justice can be done in a democracy clothed in republican colours. Republican France survived battered and weakened, yet maintaining faith in her values, when in July 1906 the three branches of the High Court of Appeals, sitting as one, declared Dreyfus innocent, that he had been convicted by “error and wrongfully”, and forbade any further trial.

Herzl did not live to see the end of the Dreyfus affair and Dreyfus vindicated of false charges, decorated with the Légion d’Honneur, promoted to the rank of Major, and reassigned in the army. The vindication of Dreyfus was a stinging defeat for the leftover forces of ancien regime in republican France and, especially, for the misnamed “anti-Semites” who were “Jew-haters.” When the Dreyfus affair broke in 1894 and Dreyfus was ceremoniously degraded in January 1895, crowds across France erupted with the chant, “A mort les juifs, a mort les juifs / Death to the Jews”. Herzl heard this chant in Paris and later wrote, “Where? In France. In republican, modern, civilised France, a hundred years after the Declaration of the Rights of Man.” Barbara Tuchman gushed about Herzl’s reaction to the chant in The Proud Tower as follows:

The shock clarified old problems in his mind. He went home and wrote Der Judenstaat, whose first sentence established its aim, “restoration of the Jewish state,” and within eighteen months he organized, out of the most disorganized and fractional community in the world, the first Zionist Congress of two hundred delegates from fifteen countries. Dreyfus gave the impulse to a new factor in world affairs which had waited for eighteen hundred years.

And thus the legend was fabricated first by Herzl and then promoted by the sharp and powerful pens of writers and journalists, European Jews and non-Jews, philo-Semites and Christian Zionists, who had found their man to write a new chapter of the “white race” and its mission civilisatrice in pushing the frontiers of European colonialism-imperialism into the “dark” spaces and vacant lands of uncivilized peoples. This is how Simon Schama expressed the birth of this legend, “Four years later in 1899, that same journalist, Theodor Herzl, would insist that the Dreyfus case had been his dark epiphany, the moment that he became a Zionist.” Amos Elon wrote, “Herzl did not invent Zionism. Others had done that before him. He forged the instruments that would put Zionism into practice, for politics is the development of power. From nothing, he created first an illusion of that power, and then the power itself which would later make possible the return of the Jews to Palestine. His unusual life is a study in character, and a measure of the political impact that can be caused by one audacious individual.” Barbara Tuchman exulted, “He cut through fifty years of verbiage in one word: statehood. A vast hedge of polemics known as the Jewish Question had in the preceding decades risen around the actual sufferers from anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe. Herzl crashed through the hedge on his opening page: ‘Everything depends on our propelling force. And what is that force? The misery of the Jews.’” And Professor Shlomo Avineri at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, observed, “Herzl was the first one to achieve a breakthough for Zionism in Jewish and world public opinion… From a marginal phenomenon of Jewish life he painted the Zionist solution on the canvas of world politics—and it has never left it since.”

A people, any people, needs legend to uplift their sense of ordinariness and inject something unique or special into their history and give it meaning for them and their progeny to cherish. Legend making is white-washing history, since no one may fault a people for ascribing to their hero virtue, courage, sagacity, as a distinct mark of that individual’s greatness. In a short, yet one of the more thought-provoking essays on the subject of greatness Søren Kierkegaard (1813-55), Danish theologian and philosopher, in ‘Off the difference between a Genius and an Apostle,’ pointed out, “Genius is appreciated purely aesthetically, according to the measure of its content, and its specific weight; an Apostle is what he is through having divine authority.”

Herzl was in his mid-thirties when he published The Jewish State, a small booklet of some twenty-five thousand words. There was nothing of “genius” that set him apart as a man of letters or science among his contemporaries, and none would see him as an “apostle” bearing any sort of divine message for any people in the end of the nineteenth century. Herzl as an assimilated Jew carried with him the prejudices of his time. That he recoiled from the petty bigotry of the lower classes directed at Jews in Vienna before he left for Paris was not uncommon for non-Jews to similarly recoil from such bigotry seen in public.

In England philo-Semitism was the mark of the educated and enlightened people of the greatest empire since that of Rome. Queen Victoria ruled Britannia. Her favourite prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, was a baptized Jew, and his Conservative government in 1876 bestowed on the Queen the title of the Empress of India. By the mid-seventeenth century Puritan revolution began to reverse the banishment of Jews from England in 1290 by Edward I. Puritan theology was shaped by the importance given to the Old Testament and the place of Jews in it as God’s “chosen people”. Calvinism greatly influenced Puritans of England, and the theology of the elect and predestination that Calvin preached giving heightened importance to the role of Jews in their return to the “holy land” and conversion to Christianity, as the pre-condition of the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, seeded among members of the Anglican church the ideology of Christian Zionism. The revocation of Edward I’s banishment of Jews in 1656 during the Protectorate or the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland brought about by the Puritan revolution under the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, opened the doors to the City of London to Jewish bankers, financiers and merchants from the Netherlands. The Jewish presence in the British isles began to grow and restrictions banning their advancement in the country going back to Edward I were incrementally removed until finally in 1858 it was agreed in the House of Lords that the two Houses of Parliament “might have their own form of oath, so that [Lionel de] Rothschild was able to swear ‘on Jehovah’ and take his seat as the first practising Jewish member of the House of Commons.”

The notion of Zion, Zionism, and Zionist ideology preceded Herzl by more than half century. It was a notion embedded in the theology of Protestant Reformation among Calvinists and who as Evangelical Christians placed much emphasis on Biblical prophecies. Central in this theology was the restoration of Jews in Palestine that was their ancestral homeland. And as Evangelical Christians promoted the prophets and heroes of the Hebrew Bible over Catholic saints, they theologically constructed the proposition, based on the teachings of Paul in Romans 11 that the Covenant between God and the People of Israel remained valid, contrary to the theology of the Roman Church, and that European Jews were Biblical Israelites. No one paused and asked in what manner Europe’s Ashkenazi Jews, descendants of the Khazars, a non-Semitic Asiatic people of Turkic origin having settled in the Caucasus migrated into Eastern Europe (Russia and Poland) following the dissolution of the Khazarian kingdom sometime between the 12th and 13th centuries, had morphed into Biblical Israelites? To ask such a question would lead to minimally acknowledge that Judaism had not become an entirely closed, exclusive, ethnocentric religion with Jews abnegating proselytizing for their faith, since Khazars came into Judaism through conversion and made no claim of an Israelite origin. Herzl’s booklet did not astonish Evangelical Christians, Christian Zionists, and philo-Semites in England and the Calvinists and Lutherans in the Netherlands and Germany; they were instead receptive to the proposition of the Jewish state, as spelled out by Herzl.

‘The Plan’ Herzl laid out in his booklet was, as he wrote, “in its essence perfectly simple… Let the sovereignty be granted us over a portion of the globe large enough to satisfy the rightful requirements of a nation; the rest we shall manage for ourselves.” ‘The Plan’ was in effect a plea to the mighty and the powerful in Europe to resolve, as Herzl described, the Jewish question, which “exists wherever Jews live in perceptible numbers.” The Jewish question was a European problem and the solution was also for Herzl a European-made solution. The Jewish question for Herzl was not, as others and most famously Karl Marx had suggested, a social or religious problem in Europe even though on occasions it took these forms. Herzl declared, “It is a national question, which can only be solved by making it a political world-question to be discussed and settled by the civilized [ergo, European] nations of the world in council.” The Jewish question became a national question due to the emancipation of Jews that resulted in the growth and spread of anti-Semitism. “The nations in whose midst Jews live,” wrote Herzl, “are all either covertly or openly Anti-Semitic.”

In Herzl’s racialist formulation the relationship between anti-Semitism and Zionism were symbiotic. In June 1895 Herzl made an entry in his Diary, “In Paris, as I have said, I achieved a freer attitude toward anti-Semitism, which I now began to understand historically and to pardon. Above all, I recognized the emptiness and futility of trying to ‘combat’ anti-Semitism” (emphasis added). Herzl was astute in recognizing that instead of railing against anti-Semitism, it would be the driver of his Zionist agenda in the making of the Jewish state. And according to Lenni Brenner,

It was anti-Semitism – alone – that generated Zionism. Herzl could not ground his movement in anything positively Jewish. Although he sought support of the rabbis, he personally was not devout. He had no special concern for Palestine, the ancient homeland; he was quite eager to accept the Kenya Highlands, at least on a temporary basis. He had no interest in Hebrew; he saw his Jewish state as a linguistic Switzerland.

Herzl’s Zionism was cultural nationalism based on the common identity of religion of European Jews. He had announced in his booklet, “We are a people – one people… It is useless, therefore, for us to be loyal patriots, as were the Huguenots who were forced to emigrate.” Moreover, as Clermont-Tonnerre had stated unequivocally in the debate on granting Jews as individuals citizenship based on the commonly held civic or secular identity in the French republic, and for Jews as a people, “the existence of a nation within a nation [was] unacceptable to our patrie.” Herzl’s claim of European Jews constituting a nation with the right to statehood was in keeping with the ideas of “nation and nationalism” that came to define the century since the French revolution. Benedict Anderson in his ground-breaking book Imagined Communities proposed defining nation as “imagined political community – and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign.” Herzl was an artist with words, a creative writer of fictions and theatre, not a historian, philosopher, or theologian. He diagnosed the malady afflicting Jews was anti-Semitism, and his proposed remedy was statehood for Jews wherein Jews would be a sovereign people. It was a leap of his imagination to assume European Jews as “one people” about whom in terms of their culture and religion he knew little. He showed no self-awareness in his booklet of the problems with his diagnosis and remedy, as his focus was on building the tools required for the task – (i) the Jewish Company as a joint stock company with requisite capital under English laws and registered in England; (ii) Local Groups of Jews as activists and members to organize emigration and assist settlements of Jews; and (iii) the Society of Jews acting as a corporate body top-down for and on behalf of Jews – and problems to be dealt with as they arise.

The Jewish state would be wherever the great European powers arrange for Jews to emigrate and establish their statehood. It could be in Palestine, or in Argentina, given to Jews and “selected by Jewish public opinion.” But wherever it happened to be, it would be as the slogan attributed to Israel Zangwill, an English Jew and writer who became a friend of Herzl, declared, “A land without people for a people without land.” The indigenous people on the land wherever the Jewish state was established, including Palestine, not being European were uncivilized and readily moved to make space for the Jewish people. “If His Majesty the Sultan were to give us Palestine,” Herzl wrote, “we could in return undertake to regulate the whole finances of Turkey. We should there form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism” (emphasis added). Herzl, the creative writer, did not fail to imagine that assembling “an outpost of civilization” would require preparatory work, as follows:

If we wish to found a State today, we shall not do it in the way which would have been the only possible one a thousand years ago. It is foolish to revert to old stages of civilization, as many Zionists would like to do. Supposing, for example, we were obliged to clear a country of wild beasts, we should not set about the task in the fashion of Europeans of the fifth century. We should not take spear and lance and go out singly in pursuit of bears; we would organize a large and active hunting party, drive the animals together, and throw a melinite bomb into their midst (emphasis added).

None of his European readers would fail to understand that the “wild beasts” Herzl referred to that required clearing, meant clearing land of indigenous people for European Jews to settle. Herzl possibly knew about the settlements in southern Africa by Europeans, especially the Dutch settlers who came to be known as Afrikaners with their strong belief in the racialist-supremacist theology of the Dutch Reformed Church based on Calvinism and how they cleared the land of natives, and the colonizing role of Sir Cecil Rhodes as a mining magnate and prime minister of the Cape Colony. Herzl approached Rhodes for loan to buy up the Turkish public debt, as he contemplated his offer to the Sultan of Turkey, but Rhodes declined. Herzl was no less a colonizer in intent and purpose than Cecil Rhodes, and for his Zionist agenda adopted the model of Dutch settlers armed with their Bibles and believing that they were a “chosen race” set out in their Great Trek between 1834 and early 1840s from the Eastern Cape Colony into the interior of Southern Africa fulfilling their “manifest destiny” to colonize lands north of the Orange River.

Soon after Herzl’s booklet got published in early 1896 and appeared in select Viennese bookstores, William Hechler (1845-1931) found a copy and became ecstatic. He immediately set out to find Herzl, made his acquaintance and became his intimate friend and enabler. Hechler was an Anglo-German clergyman and chaplain in the British embassy in Vienna. He was born in Benares, India, the holy city of Hindus to Dietrich Hechler and Catherine Cleeve Palmer sent to India by the “Church Missionary Society.” Dietrich was German born and immigrated to England, became an Anglican priest and prepared for missionary work. William Hechler followed his father’s footsteps and acquired linguistic proficiency in several languages, including Hebrew, Greek and Latin. William Hechler’s father, according to Schama, “was an active missionary among the Jews in both England and Germany, with the goal of hastening the Second Coming of the Saviour through their conversion. But in the old tradition going back to the humanist popes and the Dutch Hebraists, that conversion was not to be won by coercion, nor was it an absolute precondition of the Second Coming. What was imperative, though, for both father and son Hechler, was the return of the Jews to the Holy Land and the building of a Third Temple (Hechler Junior thought at ‘Bethel’ rather than Jerusalem).”

Hechler had visited Russia after the assassination of Czar Alexander II in 1881 and the pogroms against Jews that followed, met Leo Pinsker, physician and author of Auto-Emancipation published in January 1882, and spent time with Hovevei Zion (Lovers of Zion). Hechler told Herzl about his role as a tutor to the children of Frederick I, the Grand Duke of Baden and the uncle of Wilhelm II, the German Emperor. He would introduce Herzl to the Grand Duke and persuade him to arrange for Herzl an audience with the Emperor during his visit to Jerusalem in November 1898. In the heat of the noonday sun in Jerusalem, Herzl was introduced to Wilhelm II, given a few minutes to present his request from a prepared script that had been duly edited by the Emperor’s deputed counselor, and the Emperor’s reply was polite and noncommittal. The previous year in August 1897 Herzl called for the First Zionist Congress held in Basel, Switzerland, and in his diary noted that there he had founded the Jewish state. After his audience with the German Emperor, Herzl waited anxiously for the audience he requested with the Turkish Sultan and Caliph of the Ottoman Empire, which came in January 1902 followed by a second audience the same year in August. The Sultan was prepared to permit large-scale settlement of Jews in Mesopotamia, Syria and Anatolia, but not Palestine. Herzl declined the offer.

iv]

The sixth Zionist Congress in Basel was scheduled for August 23, 1903. Herzl decided to visit Russia ahead of the Congress with the objective of gaining support of Czar Nicholas II and his government to pressure the Turkish Sultan in granting the Zionists a charter for the colonization of Palestine. Herzl also sought Russian support for Jewish emigration to Palestine and for permitting Zionist societies within Russia to operate within the framework of the Basel program. The Russian minister of interior, Vyacheslav von Plehve, responded favourably to Herzl’s requests. On his return journey from Russia, Herzl received word that the British government was prepared to formally establish a Jewish colony in East Africa and Herzl took heart in this proposal as an interim solution while waiting for the Turkish charter for Palestine.

The offer of a Jewish colony in Uganda nearly split the sixth congress. The opposition Herzl met over Uganda, even as he sought to explain to the delegates that this would be a provisional measure in the aftermath of the Kishinev pogrom earlier in April of that year, meant striving harder to bring pressure on the Sultan of Turkey in obtaining a charter for Palestine. And this he set out to do by seeking audience with the King of Italy and the Pope that was arranged for January 1904.

Herzl was granted his audience first with King Victor Emanuel III of Italy, who expressed his support for the Zionist agenda of settling Palestine. But the king being a constitutional monarch would have to leave Herzl’s request for pressuring the Turkish Sultan to the decision of his government and the foreign minister. Herzl was left to wait for his meeting with the Pope that occurred two days later on January 26.

Pius X, or formerly Cardinal Guiseppe Sarto and patriarch of Venice, was the first Pope elected in the twentieth century in 1903, and the first Pope canonized in 1954 since the sixteenth century. Pius X was a traditionalist, at heart a parish priest who was made bishop of Mantua in 1884, and was loved by Catholics pilgrims to Rome from around the world for his warmth and gentleness and love for Catholic families and their children. According to Thomas Bokenkotter, a historian of the Roman Church, “Unlike his predecessor, Leo XIII, Sarto was little concerned with reconciling the Church with the modern world; his general attitude toward the cultural and political trends of the day was, in fact, negative and in line with a general pessimism about temporal progress endemic in postrevolutionary Church.” Herzl recorded in his diary the audience with Pius X as follows:

Yesterday I was with the Pope. I arrived 10 minutes ahead of time and didn’t even have to wait. He received me standing and held out his hand, which I did not kiss. He seated himself in an armchair, a throne for minor occasions. Then he invited me to sit down right next to him and smiled in friendly anticipation.

I began:

“Ringrazio Vostra Santità per il favore di m’aver accordato quest’udienza” [I thank Your Holiness for the favor of according me this audience].”

“È un piacere [It is a pleasure],” he said with kindly deprecation.

I apologized for my miserable Italian, but he said:

“No, parla molto bene, signor Commendatore [No, Commander, you speak very well].”

For I had put on for the first time—my Mejidiye ribbon [Awarded by the Turkish Sultan]. Consequently the Pope always addressed me as Commendatore. He is a good, coarse-grained village priest, to whom Christianity has remained a living thing even in the Vatican. I briefly placed my request before him. He, however, possibly annoyed by my refusal to kiss his hand, answered sternly and resolutely:

“Noi non possiamo favorire questo movimento. Non potremo impedire gli Ebrei di andare a Gerusalemme—ma favorire non possiamo mai. La terra di Gerusalemme se non era sempre santa, è santificata per la vita di Jesu Christo (he did not pronounce it Gesu, but Yesu, in the Venetian fashion). Io come capo della chiesa non posso dirle altra cosa. Gli Ebrei non hanno riconosciuto nostro Signore, perciò non possiamo riconoscere il popolo ebreo. [We cannot give approval to this movement. We cannot prevent the Jews from going to Jerusalem—but we could never sanction it. The soil of Jerusalem, if it was not always sacred, has been sanctified by the life of Jesus Christ. As the head of the Church I cannot tell you anything different. The Jews have not recognized our Lord, therefore we cannot recognize the Jewish people].”

Hence the conflict between Rome, represented by him, and Jerusalem, represented by me,