“Big Three” Korean Shipbuilders & Their Huge Shipyards in a World of Overcapacity and Collapsed Orders

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

Years of “growth at any cost” led to accounting fraud, huge government bailouts, and murky restructuring plans.

Years of “growth at any cost” led to accounting fraud, huge government bailouts, and murky restructuring plans.

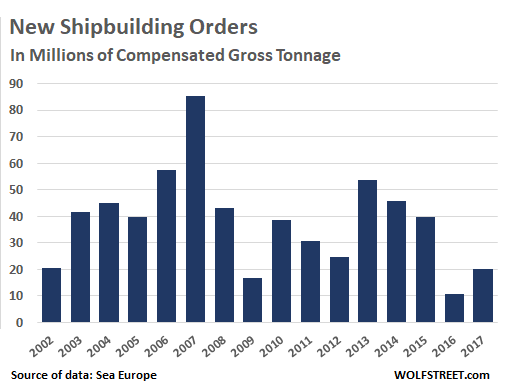

Worldwide orders for newly built commercial vessels peaked in 2007 at 85.3 million Compensated Gross Tonnage (CGT) and have never recovered, despite the boom in the intercontinental maritime trade, especially with East Asia. After a historic collapse in 2016, orders ticked up in 2017, but to a still desperately low 20.2 million CGT (new shipbuilding orders via Sea Europe):

Three countries came to completely dominate this market as of 2017: China (34%), Korea (31%), and Japan (19%), according to Japan’s Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT), which also points at a major issue: overcapacity.

The shipbuilding industry has been plagued by overcapacity since 2010 and, with new competitors emerging in cheap-labor countries such as India and Vietnam, it seems oversupply will get worse over the next few years.

Nowhere is overcapacity more evident than in Korea, where shipbuilding alone accounts for 6.5% of the GDP and where the Big Three shipbuilders alone directly employ over 200,000 workers: Samsung Heavy Industries (SHI), Daewoo Shipbuilding and Marine Engineering (DSME), and Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI).

To understand how important shipbuilding is for the Korean economy as whole, one only needs to look at Geoje Island, near the port city of Busan. Both DSME and SHI have their main shipyards on the island, in Okpo and Gohyeon respectively, and especially at Ulsan, where HHI’s main shipyard, the world’s largest by capacity, is located. Ulsan is also home to the largest car factory in the world by potential output, owned and operated by Hyundai Motor Company, a company belonging to the same chaebol as HHI.

The Hyundai Shipbuilding Division, as the Ulsan shipyard is officially known, can be considered the true poster child for the Korean shipbuilding industry: it represents its ambitions, successes, and now the many challenges facing it.

This shipyard looks like a cross between a sprawling state-of-the-art-manufacturing facility and a futuristic nightmare, stretching as it does over a massive four kilometers of coast, At the heart of this industrial conglomeration are nine dry docks and what once was the world’s first H-dock.

The H-Dock is used to build specialized vessels and floating structures, from Tension Leg Platforms (floating platforms for oil and natural gas exploration) to pipe-laying ships. The dock is 490 meters long, 115 meters wide, and 13.5 meters deep (1 meter = 3.28 feet) and is advertised as being able to build any kind of vessel customers may conceivable want.

HHI boasts that Dry Dock #3, the world’s largest at 672 meters long and 80 meters wide, a product of the unbridled economic expansion of the 1990s, can be used to build vessels up to one million DWT (Deadweight Tonnage is a measure of how much a ship can carry, including paying cargo, ballast, fuel, provisions, and crew and passengers).

All vessels over 400,000 DWT ever built proved to be unsatisfactory in service and, despite the present trend towards larger and larger ships to increase efficiency, it’s highly likely no more will be built in the foreseeable future: even the Valemax bulk carriers, which are certified for 400,000 DWT are rarely over 270,000 DWT these days. This means Dry Dock #3 is used to build two or occasionally three ships at the same time.

The Ulsan Shipyard also boasts ten “Goliath” gantry cranes; while Goliath is a trademark of Kone Cranes of Finland for their family of ultra-large gantry cranes, it has come to indicate any oversized and extremely powerful gantry crane, all the way up to the Taisun, owned and operated by Yantai Raffles Shipyards of China, which has been certified for up to 20,000 metric tons of lifting capacity, the most powerful crane in the world (image via CIMC Raffles):

On top of this, like all their competitors, the Ulsan shipyards sport state-of-the-art metal works and steel cutting lines, and one of the only four facilities in the world that can manufacture the enormous crankshafts used in the huge slow-speed two-stroke diesel engines that propel the largest commercial ships.

The cost of labor, however – though it originally propelled Korea to the forefront of the shipbuilding industry in the 1970s and 1980s when wages in Japan were growing too rapidly for shipowners’ liking – has been a major concern for Korean shipbuilders since the 1990s.

This means all Korean shipbuilders have invested heavily into automation, both to increase worker productivity and to cut the labor input needed to manufacture a ship. These technologies include:

- Trackless crawling all position arc-welding robots, highly sophisticated industrial robots that use magnets to move on the sheets of metal they are working on, laser beams to control the welding process, and carefully controlled streams of ultra-cold pressurized nitrogen to control welding shapes.

- Crawler robots to lay the miles of wiring any commercial vessel possesses nowadays.

- Fully automated paint cycles, a sorely needed process as the anti-foul paints used on keels contain biocides such as oxine-copper, a toxic and carcinogenic compound.

The commercial policies of these Korean mega-shipyards have long been driven by one simple principle modern stock market aficionados will easily recognize: growth at any cost.

Starting in the 1980s, many European and Japanese shipyards, driven ironically by competition from Korea, decided to specialize in one or a few types of ships.