Fed’s New Balance Sheet Plan: Get Rid of MBS

by Wolf Richter, Wolf Street:

In relationship to GDP, the balance sheet will continue to shrink until some magic unknown point is reached.

The Fed has a new plan for what to do with its balance sheet and today announced several major components of it:

- Begin tapering the “runoff” of Treasury securities in May.

- End the runoff of Treasury securities on September 30.

- Continue shedding mortgage-backed securities (MBS) at the current maximum of $20 billion a month, essentially until their gone.

- After September, reinvest MBS principal payments into Treasury securities.

- Chair Jerome Powell said during the press conference that the balance sheet will by then be “a bit above $3.5 trillion.”

- The balance sheet will remain at this level even as the economy grows, thus slowly shrinking in relationship to GDP.

- The Fed may sell MBS outright to speed up the process of getting rid of them.

- No decision has been made on the delicate issue of the maturity composition of the balance sheet – which would require buying short-term bills for the first time in years to replace longer-term notes and bonds.

The stated balance-sheet doctrine now is that the Fed wants to have sufficient reserves (money that banks deposit at the Fed) to conduct monetary policy efficiently. The interest it pays the banks on those reserves is one of its major tools to manage short-term interest rates.

Treasury securities.

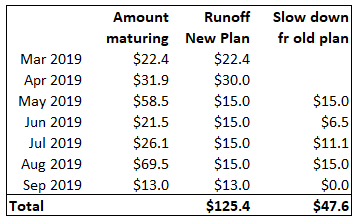

Currently the amount of Treasury securities allowed to roll off the balance sheet is capped at $30 billion a month. This cap will shrink to $15 billion a month in May.

Only Treasuries that mature in that month can roll off. The table below shows the bonds, notes, TIPS, and Floating Rate Notes (FRN) on the Fed’s balance sheet that are maturing through September. By reducing the cap from $30 billion to $15 billion, the Fed slows the runoff by a total of $48 billion. Instead of shedding $173 billion in Treasuries under the old plan, it will instead shed $125 billion:

Currently, the Fed holds $2.175 trillion in Treasury securities. By the end of September, this will be down to about $2.05 trillion.

But MBS will roll off or be sold until they’re gone.

The Fed will continue to allow MBS (and the small amount of Agency debt it still holds) to roll off at a rate of up to $20 billion a month.

Starting in October, it will still allow MBS to roll off at that rate. But it will reinvest up to $20 billion of principal payments it receives in Treasury securities. In other words, it will gradually replace its MBS with Treasuries, “consistent with the aim of holding primarily Treasury securities in the longer run.”

The maturities of these replacement Treasuries will go across the range, including bills (one year or less), of which it holds none currently.

And a kicker: It may sell some MBS outright: “Limited sales of agency MBS might be warranted in the longer run to reduce or eliminate residual holdings.”

In relationship to GDP, the balance sheet will continue to shrink.

Come end of September, the Fed will likely find that the level of reserves is still higher than “necessary to efficiently and effectively implement monetary policy.” So the plan is to reduce these reserves further, but gradually.

The reserves are liabilities. The other major liability on the balance sheet is currency in circulation (actual paper dollars stuffed into mattresses around the world). Currency in circulation is rising persistently, as a function of demand for dollars through the banking system.

Keeping total liabilities flat, even as one part of liabilities (currency in circulation) increases means that the other major part (reserves) will decrease further. That’s the intent of keeping the balance sheet flat: Slowly whittling down the amount of reserves.

Before the onset of QE, the Fed’s balance sheet rose as a function of currency in circulation and reserves. In relationship to GDP, the growing balance sheet stayed roughly in a range between 4.5% and 6% of GDP. During peak QE at the end of 2014, its assets reached around 25% of GDP, according to Powell at the press conference today; and he expects them to be down to 17% of GDP at the end of September.

As the size of the balance sheet remains flat after September, and as the economy grows, the balance sheet as percent of GDP will shrink further. That’s the plan. During the press conference Powell was asked when this slow shrinkage would go on. And he said, “The truth is, we don’t know.”

Once the reserves drop to this still unknown magic minimum “necessary for efficient and effective policy implementation” – so next year or in 10 years – the Fed will go back to growing its balance sheet in line with the economy, as it had done before the onset of QE.

During the Q&A at the press conference, Chair Powell’s clarified several hot-button issues concerning the balance sheet and monetary policy:

The balance sheet treatment is not related to monetary policy, he said. “We think of the interest-rate tool as the principal tool of monetary policy. And we think of ourselves as returning the balance sheet to a normal level over the course of the next six months. We’re not really thinking of those as two different tools of monetary policy.

Loading...