DOJ Buried Allegations That Cheney’s Halliburton Subsidiary Paid Bribes for Venezuela Contracts

by Lucy Komisar, Consortium News:

Spurred by the recent U.S. attempt to overthrow the government of Venezuela, Lucy Komisar offers a never-told story about the international corruption of state oil company PdVSA many years ago, under a pro-business administration in Caracas.

Part of the ongoing U.S. demonization of the Nicolas Maduro government of Venezuela is to accuse it of corruption. In 2017, for example, U.S. prosecutors charged five former Venezuelan officials under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) with soliciting bribes in exchange for helping vendors win favorable treatment from state oil company PdVSA from 2011 to 2015. (Hugo Chávez was president 2006 to 2013, and Maduro became president in 2013.)

However, there’s another example of PdVSA bribery that the U.S. never felt compelled to pursue. It is the alleged and never investigated Halliburton bribery of Venezuelan oil company officials in the late 1990s when Halliburton was run by Dick Cheney, who would leave it to become vice-president under George W. Bush.

Exposing that story shines a light on the political motivation of Washington’s current attacks on Venezuela.

The story involves Halliburton subsidiary Brown & Root allegedly participating in a payoff to PdVSA with its French partner Technip in order to get oil facility construction contracts in Venezuela in 1997 and 1998.

This was revealed to a French investigating magistrate by the Technip official who managed the bribe affair and who told me the story.

At that time in France, before 2000, foreign bribery was legal, only kickbacks to French individuals and companies were barred. The magistrate therefore determined there were no kickbacks and dropped the case. But his investigation was reported at the time in the French press and would have been seen by FBI officials at the U.S. embassy and by State Department analysts at the embassy and in Washington. But the U.S. ignored this story of a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act violation.

Rue des Italiens

Over the course of two years, in 2001 and 2002, Georges Krammer paid several visits to 5-7 Rue des Italiens, a classical stone edifice in the cul de sac of an elegant Right-Bank boulevard in Paris, in which a French magistrate, Renaud Van Ruymbeke, had an office.

During that time, Van Ruymbeke was investigating a bribery case concerning Elf, the state-owned French oil giant. Krammer was of interest to him because of Elf’s connection with Technip, a French company that constructed drilling-and-production facilities for oil-and-gas fields. Krammer was Technip’s general manager.

The meetings were private, but Krammer, in emails and conversations with me almost 10 years ago, described some of what was said.

At first Van Ruymbeke was mainly interested in Ely Calil, a notorious Lebanese bagman who was accused of handling Elf bribes with Nigeria but was released on appeal. But at a certain point, Krammer said, Van Ruymbeke began to zero in on Technip’s overall bribe operation in Nigeria as well as Venezuela. Foreign bribery, at the time was legal in Europe, but domestic bribery was not. He was looking for illegal “retro-commissions,” kickbacks to French citizens or political parties.

The multi-million-dollar bribe operation involved international conglomerates using partnerships and subsidiaries to conduct business with one another. A common denominator among them was the use of bribes to grease work contracts in the oil-producing nations of Nigeria and Venezuela.

For U.S. companies the international relationships were key since bribing foreign officials violated the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

One of the parent companies in this network was Halliburton, the Houston-based multinational oil-services behemoth for which Dick Cheney, the former U.S. vice president under George W. Bush, served as board chairman and CEO from 1995 to 2000.

Officials for Technip, (which has since merged to form TechnipFMC with headquarters in London), declined to be interviewed. Halliburton declined a request for comment on this article, as did Cheney’s office.

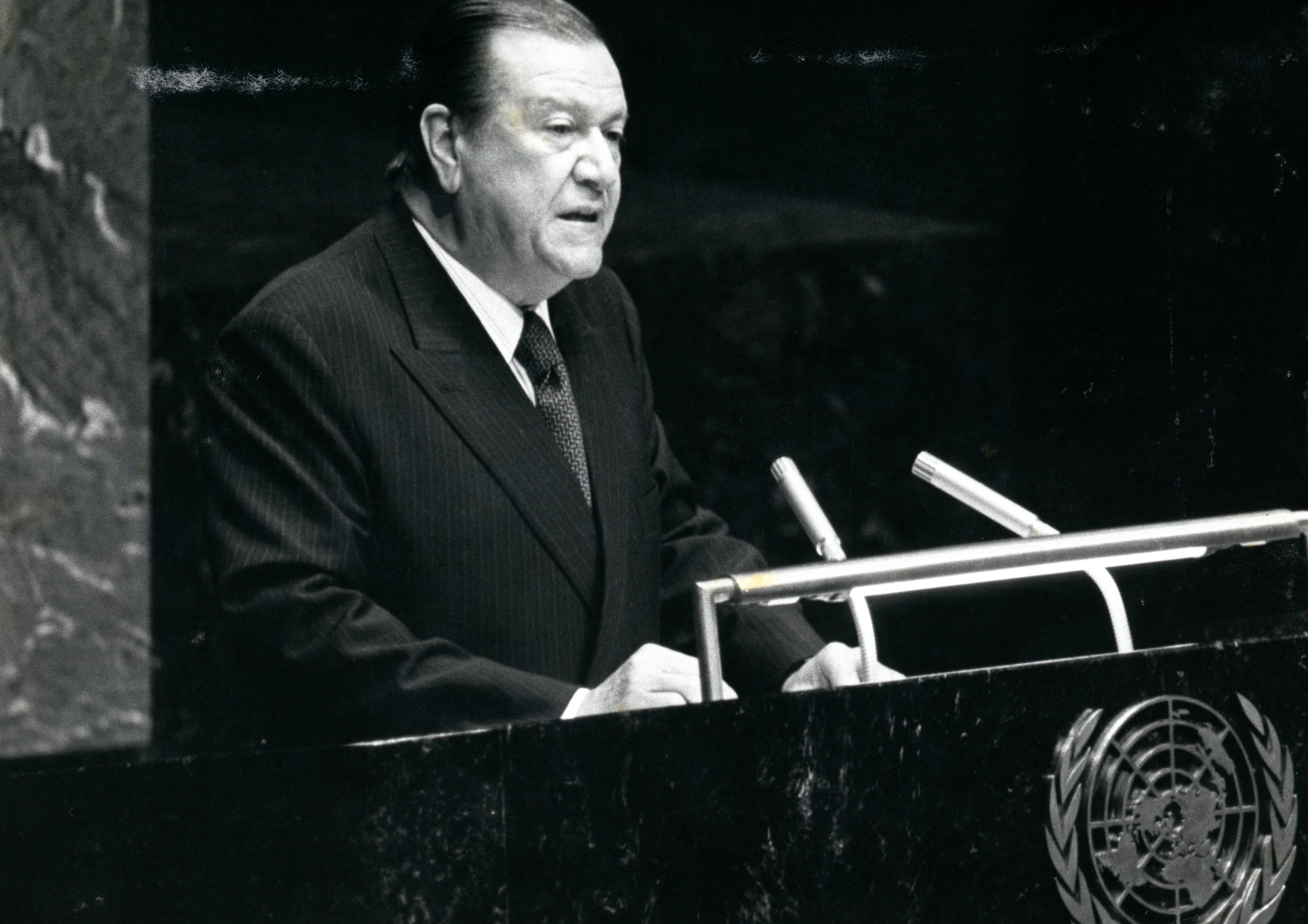

Former Vice President Dick Cheney in 2011. (Flickr/Gage Skidmore)

Venezuelan Contracts Wanted

Technip’s partners in Venezuela were Brown & Root, the engineering-and-construction giant that has since been subsumed by a merger, but was a Halliburton subsidiary at the time; Parsons E&C, a U.S. provider of construction-management services that has since been acquired; and two Venezuela firms. They wanted several contracts to build oil production facilities in Venezuela. To get them, they would allegedly pay bribes through a shell company, Contrina, which Technip set up in Paris. (Georges Krammer’s name appears in Contrina’s listing in the French corporate registry.)

“The American companies make use of the European companies to pay the bribes, because they could do it,” Krammer told me. Because bribery [in Europe] had been legal until 2000, he said European companies were expert at it. “They were working with U.S. companies,” said Krammer. “They told them we will arrange everything, don’t worry. This is how Technip operated.”

Krammer told me that the bribes were around 1.5 percent of the value of the contracts, which when combined were worth about $1.25 billion. Delivering the payments was also lucrative business. During the time Krammer was meeting with the judge, Karl Laske of the Paris daily Libération was also investigating Ely Calil. Laske wrote in October 2002 that Technip had paid bribes to get a contract to build an oil-refinery facility in Venezuela and that Calil had had been awarded $8.5 million for handling payoffs.

Ultimately, the judge did not bring the Venezuela case to court, since such bribery of foreign officials was legal in France until 2000, when OECD rules forced changes in national laws. Till then, French companies just had to report the bribes to the French Treasury.

According to French court documents, Van Ruymbeke ultimately dropped the case.

But the investigation that he began should have had consequences for some of the U.S. entities and individuals involved in the Venezuelan network.

No Probe Into Cheney

Although the Nigerian bribery was already underway when Cheney took charge, the Venezuelan operation began under the former vice president, via Halliburton’s Brown & Root.

But though the U.S. Justice Department went after and fined the companies and individuals in the Nigerian case, it never went after a Halliburton/Brown & Root Venezuela bribery operation.

Krammer said the Venezuela bribes began in the late 1990s, with contracts that Contrina signed in 1997 and 1998. They went to officials of the state oil company, PdVSA (Petroléos de Venezuela) during the administration of pro-business President Rafael Caldera, who preceded the leftist President Hugo Chávez.

Former Venezuelan President Rafael Caldera in 1980. (Sucesión Caldera Pietri/Fundación Tomás Liscano, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

The two contracts were to build facilities in Port La Cruz, on the Caribbean, that would upgrade extra heavy oil produced in the Orinoco region of Venezuela. The upgrader turned the oil into synthetic crude (syncrude), so it could be shipped in tankers to Conoco’s U.S. refineries, most of it to the Westlake site in Louisiana. The oil deposit was expected to last 35 years.

“Contrina, based in Technip offices in France, gathered the agreements of its U.S. partners to pay the bribes,” Krammer told me in an email in 2011. “Contrina SNC paid the bribes to Rossven (offshore vehicle for bribery).” He said the beneficiary of Rossven was the bagman Calil who did what was necessary.

Krammer said, “Brown & Root, Parsons and Technip signed papers that we can place the bribe with Calil.” He said the U.S. signatories on the agreement were Senior Vice President Lawrence J. Popefor for Brown & Root and Bill Hall for Parsons E&C. Payments were made in 1998 and 99. They were sent from a Contrina Paris bank account owned by Krammer.

Read More @ ConsortiumNews.com

Loading...