"Dead" Virus Cells Frequently Trigger "False Positives" In Most Common COVID Test, New Study Finds

In the past, our reports raising questions about the accuracy of COVID-19 tests have been met with accusations of 'fearmongering' and spreading 'misinformation'.

But not today.

That's because new research from the University of Oxford’s Center for Evidence-Based Medicine and the University of the West of England has found that the swab-based technique used for most COVID-19 testing is at risk of returning "false positives" since copies of the virus's RNA detected by the tests might simply be dead, inactive material from a weeks-old infection. Although patients infected with COVID-19 are typically only infectious for a week or less, tests can be triggered by virus genetic material left over from a weeks-old infection.

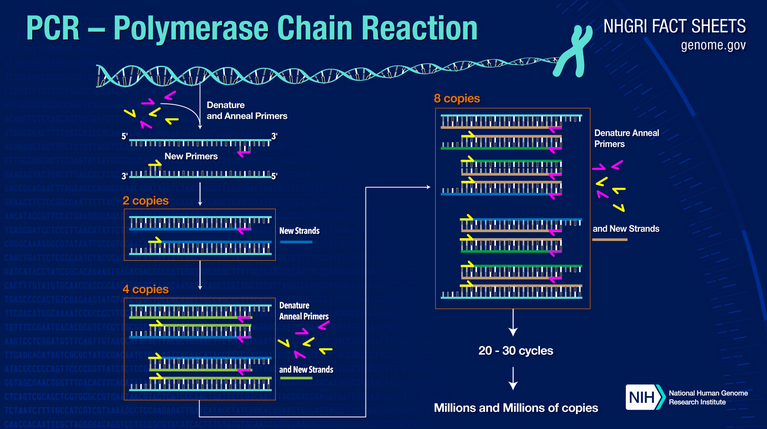

The team's research involved analyzing 25 studies on the widely used polymerase chain reaction test. PCR tests use material collected with a swab - the most common type of test around the world, and especially in the US - then utilize a "genetic photocopying" technique that allows scientists to magnify the small sample of genetic material collected, which they can then analyze for signs of viral RNA.

What the researchers here have effectively found is that these PCR tests just aren't sensitive enough to distinguish if the viral material is active and infectious, or dead and inert.

For those who desire a more comprehensive understanding of how these tests work, the chart below can be helpful.

Professor Carl Heneghan, one of the authors of the study, said there was a risk that a surge in testing across the UK was increasing the risk of this sample contamination occurring and it may explain why the number of Covid-19 cases is rising but the number of deaths is static.

"Evidence is mounting that a good proportion of ‘new’ mild cases and people re-testing positives after quarantine or discharge from hospital are not infectious, but are simply clearing harmless virus particles which their immune system has efficiently dealt with," he told the Spectator.

Professor Heneghan added that international scrutiny might be required to avoid "the dangers of isolating non-infectious people or whole communities."