Why I Read

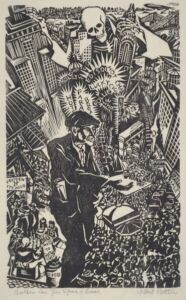

Image courtesy of Theen Moy on Flickr.

2,475 words

If I could always read, I should never feel the want of company. — Lord Byron

There’s more to life than books, you know,

But not much more.

— Morrissey

Writing has a lot in common with sex and driving in that those who take part in these activities believe themselves to be very good at them. Road traffic casualties and disappointed lovers could produce contrary arguments, but it takes a little more intellectual engagement to detect both bad writing and good. And to whom does that task fall? Why, gentle reader, to you and me, to the reader, the vital other without whom there is no writing, or even its possibility. So, it’s the reader’s turn. We already read all the “Why I write” stuff. Now it’s time for “Why I read.”

Why should writers hog the limelight? We know all about writers, all the angst and the alcoholism, the writer’s block and the desperate and desolate blank page. But writing and reading are properly dialectical, each implying the other, symbiotic and mutually supportive. Without reading, there can be no writing. Without reading, writing would be Bishop Berkeley’s tree falling in a forest with no one to hear it fall. Even a writer who writes purely for his own pleasure becomes a reader to himself. Readers deserve to be more than just a footnote in a treatise on writing.

Reading books is also becoming a small act of rebellion, a thumb of the nose at the forced cultural degradation of the West. Put simply, you should read because there are people in global positions of power who don’t want you to. Books are an antidote to the state-endorsed sleaze we are being drip-fed, and the doctor doesn’t want you to have the medicine. So read now, while you can, before the temperature reaches Fahrenheit 451.

Personal reading, the literary tracks in the snow we all leave, is also an adventure story in which not the writers but the books themselves are the main characters. Think of your own reading history, the first books, the first by those who became your favorite writers, the places where you have read books and reread them, the books you gained and the books you lost, the books you wouldn’t give up even for a worthwhile culture, never mind the foul-smelling swamp being churned out of the fresh soil of white achievement. I don’t include whiteness as a tag to keep me in with the dissident in-crowd, but because books, their whole being and purpose, is a core white project, one of which non-whiteness is no longer capable, its great civilizations being only just visible in the distant past. Whatever drove you to books, why they became a part of your life, is a large part of who you are.

I wasn’t a bookish kid. The earliest scuffle I remember with serious literature was an attempt to read Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and never getting past page 10. I finally read it a few years ago and thought maybe the boy was right. I also had a real flirtation with “The Lady of Shallott,” Tennyson’s dark poem of courtly love and possession. But reading only started when I was 12 or 13, when I discovered science fiction and stayed with it, pretty much uninterrupted, until I was 16.

So it was that I kept the company of Asimov, Clarke, Bradbury, Moorcock, Heinlein, Vonnegut, and many more up until I started sixth-form college. I read Lord of the Rings when I was 14 — an appropriate age, I feel — and would race home from school to read my 50 pages before bed. Then, in my first A-level English Literature class, I pocketed my copy of Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker in favor of a book lent to me by another student: Orlando by Virginia Woolf. Serious literature opened up to me, like an Eleusinian Mystery. I went to university to read Philosophy with Literature and ended up cheating on literature and walking out arm-in-arm with the Lady Philosophy. The first time I saw the philosophy section in the university library, I wished the books I needed would announce themselves to me, make themselves known. But it doesn’t work like that; you have to go looking. Then, when you do, the old phrase of the alchemists will come into play; one book opens another.

I won’t bore you any longer with the life and times of a compulsive book-reader, but I just wanted to illustrate that we all have our story of how we found books, or how they found us. And they do find us. Recently, in a bar which has a few battered old books on its shelves, I found an original Penguin copy of Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim. I had to sellotape the covers back on, but I read its sepia-edged pages with all the more enjoyment. Two of my favorite modern novels, Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, came from the same charity shop on different visits. I had heard of neither author prior to my visits. I talked music and books with a fellow boater on the deck of my canal boat one evening, and lent the guy my copy of Nowhere to Run, Gerri Hirshey’s brilliant history of soul music. When I woke next morning, the other boater had gone. With my copy of Nowhere to Run. I was slightly miffed until I saw, on my deck but covered against the rain always possible in England even on the finest day, a copy of one of George McDonald Fraser’s Flashman novels, which I had bemoaned the night before never having read. I’ve all 12 now. Some books do find you; they do call out and make themselves known, the way Arthur Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Idea made itself known to the 21-year-old Nietzsche in a secondhand bookshop in Leipzig.

A book walked into my life this last week. I have just moved house and, after a long day, I felt like reading a book — a real book. Much as I venerate the existence of e-books, and the fact that the complete works of Plato, Shakespeare, Zola, and Conrad are all on my phone and cost me a combined total of around the price of half a pint of beer in London, I do require the reality of a physical book from time to time. The problem is I only have about 30 books, having left over a thousand in England when I jumped ship, and as a result I have read all of them at least twice. Books are not ideally suited to the nomadic life, and were a huge headache for Byron as his entourage trundled across Europe. Nietzsche often cursed the impracticability of his own trunk of the books he felt he couldn’t travel without.

You can buy Mark Gullick’s novel Cherub Valley here.

My landlord invited me to look at his shelves, and I selected an old volume more or less at random. It is The Life and Death of a Spanish Town by Elliot Paul, and it was published in 1937.

“Oh, that,” he said. “It’s about Ibiza.”

Now, the Spanish island of Ibiza is a familiar name to most Brits, but for unsavory reasons. For the past few decades, it has been the favored destination of the most depraved, degraded, and debauched young Britons those islands can muster. They go there to drink, drug, and copulate themselves into the void, and all set to a nihilistic musical soundtrack. They will not have packed much in the way of holiday reading and are unlikely to have an interest in Spanish history. But Life and Death was published two years before the Second World War, and so was unlikely to include a guide to finding safe Ecstasy pills.

My landlord’s mother had lived much of her life on Ibiza, and he had himself lived on the island for a time. The book is a history of Santa Eulalia, a town on the island, from the point of view of its people as they approached the Spanish Civil War. This is not a review of the book, as I am halfway through its 400-odd pages, and it is one to savor. But the opening paragraph is worth quoting in full as it is as good a come-on for a book as I have read, plus its first sentence is masterful. I read it, and felt secure in the knowledge that I would both read and enjoy what was to come:

There is so much revolution and class war going on in all parts of the world that I believe it will be of interest to American readers to know how fascist conquest, communist and anarchist invasion, and the bloodiest war yet on record affect a peaceful town. By a town, I mean its people. I knew all of them, their means and aspirations, their politics and philosophy, their ways of life, their ties of blood, their friendships, their deep-seated hatreds and inconsequential animosities. Because Santa Eulalia is on an island, the inhabitants were unable to scatter and flee, and therefore I was able better to observe them and to know what happened to them as I shared their experience.

And that is the ground note for reading, a book which asks you to read it. Not an author with cover blurbs from her mates all over her latest piece of sensitivity reader-sanitized fodder, and her slot on morning telly sorted by an agent, but a first paragraph that guarantees I will finish the book and like it. There are only two authors two or more of whose books I have started but never finished any of them. For my part, you may consign to the flames the works of Stephen King and Norman Mailer. The only book whose last page I read before turning back immediately to page one to start reading it again is Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

The Life and Death of a Spanish Town is also historical, and what there is of my historical knowledge comes as much from fiction as fact. In the book’s first half, the town and its people are laid out minutely, the coming war scarcely mentioned. Franco’s war against the Republicans is just disturbingly and uncomfortably present in the book, like the wedding guest in Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Mr. Paul has some gemlike phrases. “Patience,” he writes, “makes women beautiful in old age.” And the author’s opinion on the impractical Spanish temperament made me smile, as it is applicable across the Latino world:

As a matter of fact, Ramon was the best mechanic on the island, which is not saying much. Mechanical work is not a Latin gift . . .

After adjusting to the languid but detailed prose style, I realized that although the coming conflict is only occasionally alluded to in the first half, it is foreshadowed in the slightly sinister constructions and phrases present even in the most mundane of scenes:

Very often the postmaster’s cross old wife, sitting with her back to the road and the passers-by, spins wool from local sheep into yarn with a rattling ancient spinning wheel and later knits white socks of the highest grade for her defective menfolks [sic] to wear.

Another aspect of reading, should you so wish, is that each book turns into its own mystery story (even if it is a mystery story). I am now into the second half, and war and the rumors of war have begun in earnest. It will be an education, given that the entirety of my knowledge of the Spanish Civil War comes from Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. The best books are the ones you think about as soon as you wake, eager to get back into the fray and move on to the next. I read two books a week, around 100 a year. I’m 63. Let’s say I make 75. 1,200 books left. That thought worries me far more than nuclear war or cancer.

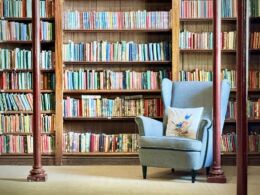

Where you read is as important as the choice of club to a golfer. It has to be just right, and I have yet to settle in my new apartment. An old friend of mine once showed me his room, dominated as it was by a vast and good-quality wicker chair. “That,” he said wistfully, “is where I read everything.” I understood immediately, as I, too, had my reading chair where I read the world, or as much of it as I could.

One reason I miss English pubs is that I can’t read in them anymore. I am so convinced of my headstone epigraph, I even had Google Translate Latinize it for me: Sextuarius in una manu et liber in altera. “A pint in one hand and a book in the other.” “Pint” is translated as sextuarius, and when you translate it back, you get “liter.” On perusing Wikipedia — how much more do we read since the Internet? — I discover that a sextuarius was equivalent to around 95% of a good old British pint, so I believe the construction stands. Anyway, a decent boozer with a decent book was Elysian Fields to me. A red-letter day was a visit to a town close to my hometown which had, at one time, five different charity shops — or “thrift stores” in American — in its high street. All of them sold books, and I would sit in The Foxley Hatch (now refurbished and spoiled, I’m told, but at least still open) and go through my piratical haul. A pub and a book allow you to be both bibulous and biblious.

Of course, there is no need to be obsessive about reading. Reading and writing form the greater part of my waking life, but I appreciate that folk do have other things to do and can’t lounge about turning pages and stroking their chins all day. That is not supposed to indicate the ease that comes with comfortable wealth, incidentally. I live well under the poverty line as defined by the World Health Organization — way under it. But reading is a poor man’s occupation. It is also an expression of your personal liberty in an age where powerful people wish to curtail your freedoms. “Libraries,” as Manic Street Preachers observed, “make us free.”

So, and without being avuncular, if reading is not a part of your life, then make it so, and if it already is, make it more so. Reading provides solace in an increasingly chaotic, disjointed, and unlikable world; a separate peace, a world apart. And unlike that world, books will never let you down, they will be your best friends forever, just like the kid at your infant school said he would be that time in the playground. But the kid lied; little children are always lying. Books, even if what they contain is not true, never lie.