How California stayed with gold when the rest of the U.S. adopted fiat money

by JP Koning, BullionStar:

We are ten years into the age of bitcoin. But people are still using national currencies like yen, dollars, and pounds to buy things. What does history have to say about switches from one type of monetary system to another? In this post I’ll dig for lessons from California’s successful resistance to a fiat standard that was imposed on it in the 1860s by the rest of the U.S.

We are ten years into the age of bitcoin. But people are still using national currencies like yen, dollars, and pounds to buy things. What does history have to say about switches from one type of monetary system to another? In this post I’ll dig for lessons from California’s successful resistance to a fiat standard that was imposed on it in the 1860s by the rest of the U.S.

Not long after the war American Civil War broke out in 1861, a run on New York banks forced most of the country’s banks to stop redeeming their banknotes with gold. A few months later Abraham Lincoln’s Union government began to issue inconvertible paper money in order to finance the war. These notes were popularly known as Greenbacks.

$1 legal tender note, or greenback

$1 legal tender note, or greenbackThus the 19 states in the Union shifted from a commodity monetary standard onto a fiat monetary standard. But Californians, who had been using gold as a payments medium for the previous decade-and-a-half, chose not to cooperate and continued to keep accounts in terms of gold. As a result, California stayed on a gold standard while the rest of the Union grappled with fiat money.

This had very different repercussions for prices in each region. As the Union issued ever more greenbacks to finance the war, the perceived quality of these IOUs deteriorated. Through much of 1863 and 1864, their price fell relative to gold. Because prices in the Union were set in terms of greenbacks, consumer and wholesale prices rose rapidly.

U.S. Index of Wholesale Prices (NBER)

U.S. Index of Wholesale Prices (NBER)In California, on the other hand, prices continued to be set in gold. Thus Californians did not experience significant inflation during the Civil War.

The waging of California’s monetary civil war

Why did the east so easily switch onto a fiat dollar standard whereas California continued to define the dollar in terms of gold? By the 1860s, most Americans who lived east of the Rockies dealt primarily in banknotes. These notes, which were issued by private banks and convertible into gold on demand, circulated widely. Gold coins, which were heavy and prone to wear, were largely confined to bank vaults.

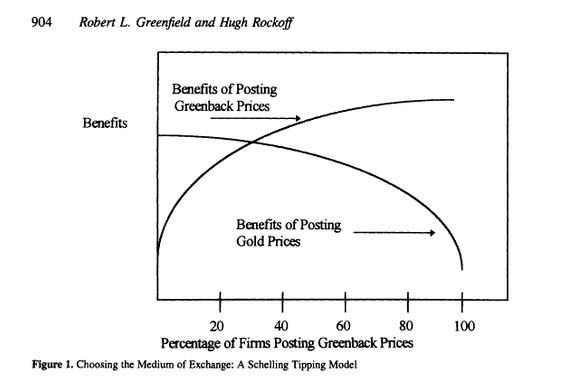

Economists Greenfield & Rockoff (2006) write that if “most people use a particular money, then everyone else has good reason to use it.” But if most people refuse to use a money, then any given individual has no reason to adopt it. In the chart below, the more firms that choose to post prices in greenbacks, the greater the benefits to any individual firm of posting prices in greenbacks. And vice versa with gold. According to Greenfield & Rockoff, a nation will naturally “tip toward” either general refusal or general acceptance of a given monetary instrument .

From Greenfield and Rockoff, “Yellowbacks out West and Greenbacks Back East: Social-Choice Dimensions of Monetary Reform”

From Greenfield and Rockoff, “Yellowbacks out West and Greenbacks Back East: Social-Choice Dimensions of Monetary Reform”When private banknotes became inconvertible in 1861 and the prices of gold and banknotes began to diverge, shopkeepers all across the U.S. had to decide which of these two instruments would serve as their accounting unit. For instance, if a horse merchant chose to sell horses at $4, did that mean that a customer owed $4 worth of greenbacks, or $4 worth of gold coins? The decision was an important one, since by 1864 one greenback would be worth just 40 cents in gold. Given that banknotes were already the dominant form of doing business in the east, shopkeepers in most Union states converged on banknote-based pricing.

But Californians had never been fond of banknotes. The 1849 First State Constitutional Convention had prohibited the chartering of banks and issuing of bank notes:

but no such association shall make, issue, or put in circulation

any bill, check, ticket, certificate, promissory note, or other

paper, or the paper of any bank, to circulate as money

[California, 1853 #64, Article IV, Section 34]

Suspicion of banknotes ran so strong in California that when businessman Samuel Brannan tried to establish a note-issuing bank in 1857, the following was printed in the Evening Bulletin:

Mr. Brannan, attempts to violate the Constitution of the State, and to fasten upon the community that most pernicious of all evils, a shin-plaster currency….The evils of shin-plaster currency are so great, and the wishes of nine-tenths of our people are so bitterly opposed to its introduction, that we call upon every individual who has any regard for the interest of our State financially or otherwise, to repudiate Mr. Brannan and his shin plasters. (Cross, 1944)

According to Cross (1944), people referred to banknotes as shin-plasters because they were about the size of the plasters put on the injured shins of farmers and other outdoor workers.

Needless to say, Brannan’s notes never took hold. In place of banknotes, Californians had always preferred to pay each other with physical gold. With the discovery of the yellow metal in 1848 in California, the state had plenty of the stuff. Gold dust, despite its inconvenience (see below) was a popular early medium of exchange. Later on, private and government-issued gold coins also became important. Non-chartered private banks existed, but they issued only deposits, not notes.

Loading...