Pour Dieu et le Roi!

As you probably already know, the “Left wing” versus “Right wing” political chasm first appeared when it cracked through the French National Assembly during the Revolution of 1789, when defenders of France’s monarchy and the Catholic faith positioned themselves on the right side of the Assembly, and supporters of the republican revolutionaries aligned themselves on the left side. The most technically correct and pedantic definition of “Right wing” is therefore a political system or ideology which favors hierarchy, aristocracy, monarchy, tradition, and Catholicism. The original definition of “Left wing” would be a political system or ideology which favors egalitarianism, the common man, republicanism, deviance, and secularism.

For this reason, one could argue that the United States has never had a true “Right wing,” given the motives behind the United States’ creation and the beliefs of the Founding Fathers. It can also be argued that there are very few strictly-speaking “Right wing” parties or movements in Europe, or indeed the world. Such has been the total triumph of “Left wing” ideology that, insofar as “Right wing” institutions or individuals exist, they often end up pledging allegiance to a few or even several “Left wing” values. Finding a “Right winger” today who doesn’t extol the virtues of equality, pander to the working class, and who doesn’t sing the praises of democracy is more difficult than finding a competent Straight White Male in a television commercial.

Even in countries that still maintain a monarchy, such as Spain, where the motto of the Guardia Civil and the rallying cry of patriotic Spaniards is “¡Viva España, viva el Rey, viva el orden, y la ley!”, or the United Kingdom, whose unofficial but most popular national anthem to this day implores God to save their monarch, the “Right wing” parties don’t make loyalty to the King or defense of the True Faith a fundamental part of their politics. Indeed, they usually sound no different than the “Left wing” parties with regard to the concerns they purport to have, their motivations, and the very policies they seek to implement.

It’s worth pausing, from time to time, and appreciating the 200-year-old paradigm you were born into, have been living in, and will likely die in. We have been pulled so far to the left, and the foundations of the West have been so thoroughly undermined, that we have come to mistake genuine “Right wing” thought with its ugly and retarded step-sister, “conservatism.” You will never know what it’s like to live in an aristocratic hierarchy. You will never know what it’s like to be inspired by a King who loves his people. You will never know what it’s like to experience politics as anything other than a sideshow of clowns attempting to appeal to the lowest of the commoners.

I can already hear some scoffing objectors, jowls all a-jiggle. “Harumpf. You’ll also never know what it’s like to be condemned to your station in a feudal system. Phiss. You’ll never know what it’s like to be vulnerable to the whims of an out-of-touch nobility.” To that I say, are we truly as socially mobile as we like to think? Is the amount of digits in your bank account or cars in your driveway a true measure of your worth, as opposed to your worth being your station in and of itself and the responsibility with which you fulfill your station’s duties? As for being vulnerable to the nobility’s carelessness or malevolence, are we any more protected from the men and women of Davos? Are we any more protected from global capitalists and multinational corporations? If monarchies are dangerous because they can go awry and be difficult to get rid of, what then do we say of permanent Washington, of the Deep State?

There will always be those who rule and those who are ruled. That’s why I’m not much of an ideologue, anyway. Monarchy, democracy, Communism, fascism . . . If I’m on any side, it’s the side of G. K. Chesterton when he said:

An honest man falls in love with an honest woman; he wishes, therefore to marry her, to be the father of her children, to secure her and himself. All systems of government should be tested by whether he can do this. If any system — feudal, servile, or barbaric — does, in fact, give him so large a cabbage-field that he can do it, there is the essence of liberty and justice. If any system — republican, mercantile, or Eugenist — does, in fact, give him so small a salary that he can’t do it, there is the essence of eternal tyranny and shame.

That said, I can’t shake the feeling that I’ve missed out on something. I can’t really know one way or another if a monarchy is better at providing a man with a cabbage field than other systems. So few monarchies remain, and the ones that do only exist as a decoration. Furthermore, the general consensus regarding monarchy and nobility is that they are bizarre hangovers from a bygone time, utterly useless and meaningless in today’s world, a caste of parasites living off the working man’s taxes, contributing nothing to society. Despite the bloody carnage that came along with the forced downfall of Europe’s royal families, the rebellions against the aristocracy are seen as, if not a good thing, at least an inevitability and a necessity.

You can buy Jonathan Bowden’s collection The Cultured Thug here.

For a twenty-first century film to take a sincere and unapologetic monarchist and Catholic stance in its portrayal of France’s grand revolution would be a thrilling act of contrarianism. Vaincre ou Mourir is a film which does just that.

Vaincre ou Mourir [Win or Die] is a 2023 film directed by Vincent Mottez and Paul Mignot, with Mignot also writing the script. It is the first film produced by Puy du Fou Films and was later picked up and distributed by the much larger and prestigious StudioCanal. It tells the story of a French nobleman with one of those fantastically elaborate names: François Athanase de Charette de la Contrie, known as Athanase to his close friends and family, but to everyone else — and to history — he was simply “Charette.” Charette would lead an army of royalist Catholics during the War in the Vendée against the republican revolutionaries.

The movie was originally intended to be a documentary-fiction, something perhaps akin to Netflix’s recent productions on Cleopatra and Alexander the Great. As development continued, however, the filmmakers realized that they had a true épopée on their hands, and the project evolved into a historical drama. Remnants of the film’s documentary origins are present right from the beginning. Various talking heads — historians, writers, professors — provide the context for the Vendée War and details about Charette.

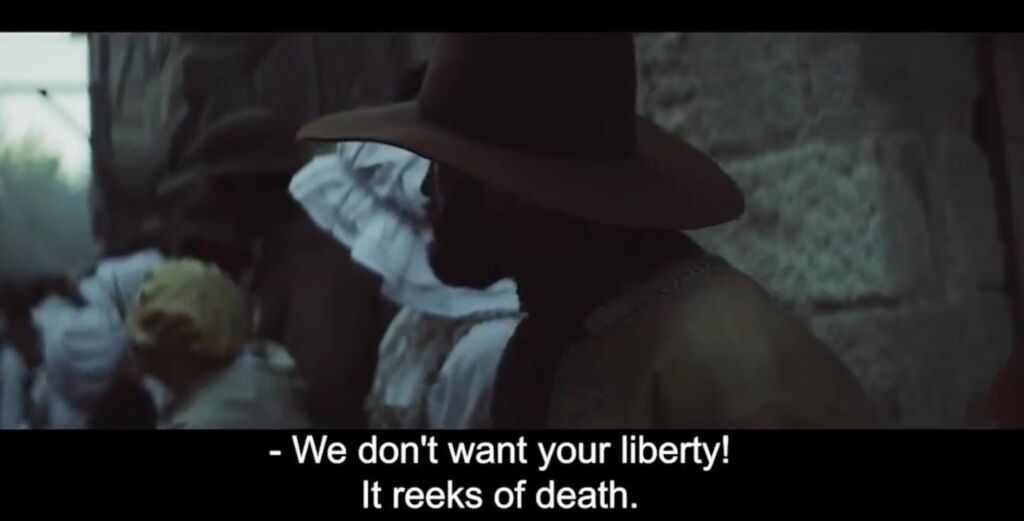

From then, the film moves fast. Very fast. I might go so far as to say that the film moves too fast. In keeping with its documentary roots, Vaincre ou Mourir doesn’t spend much time developing characters or establishing the setting. The experts’ exposition from the opening scene is sufficient to inform the audience about the situation and the protagonist. From the documentary-style preamble, we proceed directly to voiceover narration by Charette himself, who also quickly sets the stage for us. There are a few obligatory scenes of Vendée peasants expressing their dissatisfaction with the Republic, followed by an act of bloodshed that cements anti-republican sentiment amongst the villagers, but apart from this we are almost immediately plunged into Charette’s rebellion.

I suspect that the decision to use interviews with historians at the outset and narration by Charette to guide the audience while the film moves at a rapid pace was probably heavily influenced by the fact that Vaincre ou Mourir had a budget of around five million euros. Despite such a potentially restrictive amount of funds, the film doesn’t come across as cheaply made. The costumes are exquisite and the eighteenth-century settings look believable. So many Hollywood films set during any time in Europe when swords were still used are all shot in a blue-grey fog and everything looks dirty; Ridley Scott’s Napoleon being the latest example. Vaincre ou Mourir bucks the Hollywood convention and actually has scenes full of sunshine and bright colors.

You can buy Trevor Lynch’s Classics of Right-Wing Cinema here.

The limited budget is noticeable during the battle scenes, which are probably the film’s weakest points. If you don’t have the money to shoot epic battles . . . don’t try to shoot epic battles. Mottez and Mignot thought otherwise, but end up giving us a sort of film-by-numbers display of the battles: heroic low-angle shot of Charette on horseback, slow-motion scenes of soldiers stabbing each other, extreme close-ups of haggard men’s faces as the sad music plays and they take stock of the carnage and the glorious dead. You’ve seen it all before, and by now it seems a bit rote. A similar criticism can be made in the way Vaincre ou Mourir treats its characters. Due to the low budget, it can’t afford to be a three-hour epic, so things have to move quickly. Character development is sacrificed for story — and that’s fine — but then spare us the drawn-out, melodramatic scenes of characters whose names we can barely remember and don’t really care about (because the film hasn’t spent any time making us care about them) meeting their demise. At times it feels as if Vaincre ou Mourir wants to be a grand Hollywood drama à la Braveheart or The Patriot, but it would have been better if the filmmakers had embraced their limitations and kept the story grounded on its inherent pathos and inspiring main character, rather than trying to be something that it couldn’t, and that we’ve all seen a dozen times, anyway.

This is because the story behind Vaincre ou Mourir and the heroic Charette truly is remarkable and worth telling, especially nowadays. In fact, such was the bravado of the film’s pro-monarchy and pro-Catholic sentiments that the French Left and mainstream media reacted with fits of rage. However, as the historians say at the start of the movie, the Vendée War is still an open wound, and even if France has moved on (forcibly, one might argue) to love the Republique, the men and women who fought and died for love of King, for the freedom to practice their religion, and the right to maintain their traditions were genuine heroes in their own right. Their story deserves to be told.

It may not be the greatest film you will ever see, but for the story it tells and the panache with which it is told, I would recommend Vaincre ou Mourir to anyone, particularly anyone who is tired of “woke” Hollywood tripe. I consider it to be an example of “Right wing” or “nationalist” cinema that complies well with my Guide.

There is absolutely no forced “diversity” or “inclusion” to be seen, and unless you’re a revolutionary republican, you will find the film’s message and the virtues it celebrates pleasing to watch.